The entire commodities spectrum rallied in the first half of 2022 as the war in Ukraine sparked major supply concerns for energy and agricultural commodities. But heading into 2023, it is demand concerns that have taken over and are clouding the outlook. Gold and oil have lost their shine amid worries that the Fed and other central banks may overtighten, and that China is not doing enough to boost its economy after a year of jumping in and out of lockdowns. Will there be a turning point in 2023 or are even deeper losses in store?

Will gold shine more in 2023?

Historically, gold was considered a safe-haven asset, but that narrative changed this year. Yes, it hit a record high in August 2020 as investors sought shelter in precious metal due to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic and came just shy of retesting that record in early March following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That said, it was all downhill thenceforth, even as concerns about the performance of the global economy remained elevated.

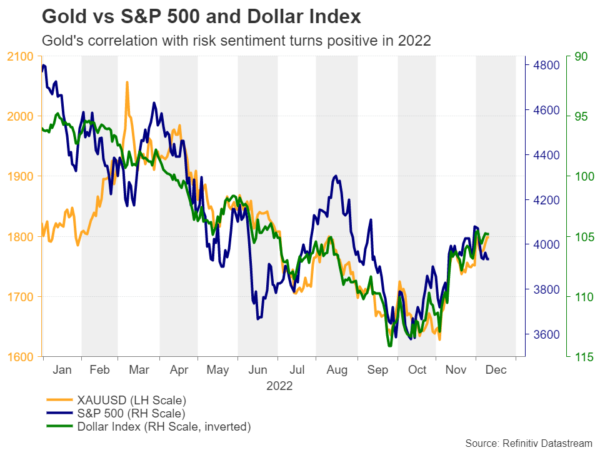

With inflation getting out of hand due to the supply shortages caused by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, central banks around the globe are prioritizing the fight against inflation rather than restoring economic activity. Ergo, as interest rates around the globe rose at a fast pace this year, at least up until a couple of months ago, the non-yielding gold lost its allure. The title of the ultimate safe haven was passed to the US dollar as with the Fed raising rates more aggressively than other major central banks, it became the only safe-haven currency that also offered high yields. Gold has therefore developed a positive relationship with equities, while reinforcing its negative one with the dollar.

That relationship is also the reason why the precious metal has staged such a comeback in November. With inflation in the US coming down faster than previously anticipated, investors have significantly lowered their expectations with regards to the Fed’s future course of action.

A worsening of the global outlook in the coming months as the effect of higher interest rates continue to be reflected in the data could well weigh on equities, while the dollar could attract some safe-haven flows, resulting in another leg south in gold. However, with the base effect of the rally in oil prices expected to drop out from the year-on-year consumer-price calculations in coming months, headline inflation may continue to come down in 2023. This would add credence to investors’ assessment of a potential Fed pivot sooner rather than later and may limit any losses in the yellow metal.

Combined with deeper economic wounds, expectations of lower interest rates during the second half of 2023 could even allow bullion to reclaim its safe-haven status in an environment where yielding assets are not as attractive anymore. Therefore, even if gold pulls back at the start of 2023, it could very well shine again thereafter, perhaps during the second quarter or second half of the year.

A potential retreat in gold could encourage some buyers to enter the game from near the $1,680 zone which acted as a floor between April 2020 and July 2022. If the rebound is strong enough to take the metal above the $1,805 zone, the rally could extend towards the high of April 18, near the psychological round number of $2,000. For the picture to turn bearish again, a break below the temporary floor of $1,615 may be needed, as this will confirm a lower low on the weekly and monthly charts.

Copper and iron ore traders keep gaze locked on China

Industrial metals, like copper and iron ore traded in a more volatile manner during 2022, suggesting a stronger link to changes in risk sentiment. Indeed, the correlation coefficients as well as the betas of both copper and iron ore with the S&P 500 have been higher than those of gold, with copper holding first place and confirming its “global economic bellwether” status due to every major sector of the global economy using copper. That said, both metals may have an extra sensitivity to developments surrounding China, as the world’s second largest economy is the number one importer of both copper and iron ore, while it holds the third place in terms of production.

Thus, further weakening of global manufacturing activity and a further slowdown of China’s economy due to the COVID related restrictions and the battered property sector may keep weighing on industrial metals for a while longer. However, hopes of more loosening of restrictions, albeit at a slow pace, and an eventual reopening could keep any setback limited and even lead to a rebound.

With the global outlook expected to be gloomier though in the next few months, those industrial metals may rebound at a later stage than gold, as gold could enjoy some safe-haven flows at a time when the others are still feeling the heat of the deteriorating global economic activity.

As crude oil languishes, a comeback cannot be ruled in 2023

It is no exaggeration to say that it’s been one big rollercoaster year for crude oil. Having started 2022 at $75 a barrel, oil prices skyrocketed soon after, spiking above $130, as the terrible events unfolded in Ukraine. But with 2022 almost over, oil prices have wiped out all those gains amid growing pessimism about the demand outlook.

The concerns primarily centre on the expectations that the major economies are headed for recession, with some likely already in one, even as it becomes increasingly difficult for Russia – the world’s second largest oil producer – to tap into the oil market. Russia’s war on Ukraine prompted several countries to restrict Russian energy imports, amongst a host of other products. But those sanctions have just gotten a lot tougher.

The G7, along with the European Union and Australia, have agreed to implement a price cap on seaborne Russian oil. The way the price cap works is complicated and there are question marks about how successful it will be. The Americans and Europeans effectively want to prevent Russia from selling oil at a price higher than $60/barrel with the intention of slashing Moscow’s oil revenue. But there is a cost, as they would further cut off Russian oil from the market at a time when energy prices remain relatively high.

The threat of supply tightening significantly over the course of the year is the biggest upside risk for the commodity in 2023, something that could be accentuated if demand from China continues to stabilize or even start to increase soon. But that’s not all.

Looking further afield to next winter, there is a danger of another positive shock for oil and other energy prices. A mild autumn in 2022, the ability of European nations to stock up on oil and gas before the sanctions fully kicked in, and demand destruction caused by the price surge from earlier this year have all contributed to energy prices sharply coming off their March and June peaks.

Unless there is additional demand destruction, which would be extremely difficult without a steep global recession and even more so if China reopens its economy, oil supply could tighten substantially further, pushing prices higher again in the second half of 2023.

But this isn’t the only uncertainty that hangs over the outlook. It is yet unclear to what extent the oil price cap will impede the flow of Russian oil and whether OPEC would attempt to offset those losses with a production increase. Moscow has said it will not agree to the price cap, although it is already being forced to sell at a heavy discount from the market price amid the ban from many countries.

If Russian oil continues to make its way into the market, and let’s not forget, it was never the West’s intention to completely block all exports as that’s not desirable for neither side, there may be more downside for oil futures in 2023, at least in the first half.

European gas crisis: the worst may be over

The outlook for natural gas is similarly cloudy. Dutch Natural Gas Futures (TTF) have fallen about 60% from their August peak when the price hit 345 euros/MWh, as efforts by European governments to reduce consumption as well as to find alternative sources of natural gas other than Russia appear to have gone some way in easing the shortages.

However, going forward, much will depend on how quickly European countries are able to replace Russian gas with either renewable energy or secure long-term supplies from elsewhere, such as liquified natural gas (LNG) exports from the United States. Both would require heavy investment of new infrastructure to become viable alternatives – something that could take years.

The only problem here is that unlike oil exports where it’s the Europeans that don’t want to buy Russian oil, it is Russia that does not want to sell gas to the Europeans. Gas flows across the continent have dwindled, and with the crucial Nord Stream pipeline now damaged and no longer operational, it would be impossible for Russian supplies to return to pre-crisis levels even if the war were to end.

This means that in spite of the recent pullback and the likelihood of some further declines, as well as barring any surprises from the Russia-Ukraine conflict or a prolonged cold snap this winter, gas prices are set to stay at historically elevated levels for the foreseeable future.