Executive Summary

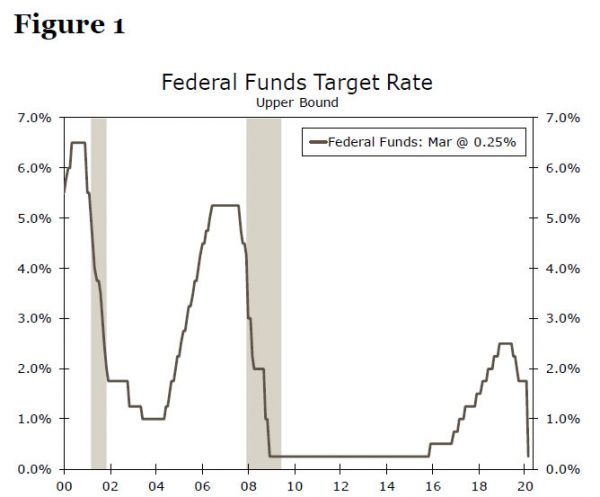

After raising its target range for the fed fund rate 225 bps between December 2015 and December 2018, the FOMC has rapidly reversed itself (Figure 1). Indeed, the committee unanimously decided to slash rates 50 bps during an extraordinary conference call on March 3, and then managed to top this with an even more extraordinary move on March 15, when it returned the target range to 0.00%-0.25% and restarted quantitative easing (QE). With short-term rates in the United States back at 0% again, the question that naturally arises is whether the Fed has run out of ammunition.

In this report, we discuss what policy tools remain at the Fed’s disposal to combat a period of economic weakness that appears to be in train in the U.S. economy. These options include: forward guidance to signal the fed funds rate will remain at zero for an extended period of time, additional QE purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the resurrection of several alphabet-soup programs created during the 2008 financial crisis, such as the recently revived Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) and the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), and the expansion of asset purchases into short-dated (six months or less to maturity) municipal debt. Although these tools should be helpful in the event of their eventual adoption, they are unlikely to solve the current economic challenges alone. For that, it will likely take a significant fiscal salvo, a topic we explore in a separate piece.

Forward Guidance and Standard Quantitative Easing

First, recall that the FOMC undertook “forward guidance” when the economy was still crawling out of the depths of the Great Recession. For example, the policy statement that was released at the conclusion of the May 1, 2013 FOMC meeting stated “the Committee expects that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy will remain appropriate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends and the economic recovery strengthens.” By publicly committing to keep the target range for the fed funds rate at extraordinarily low levels for a considerable length of time, the FOMC was attempting to pull down long-term borrowing costs. In the current environment, the FOMC could either commit to keep its target range low until some objective was met (e.g., the unemployment rate has fallen to at least some specific level) or for some specific length of time.

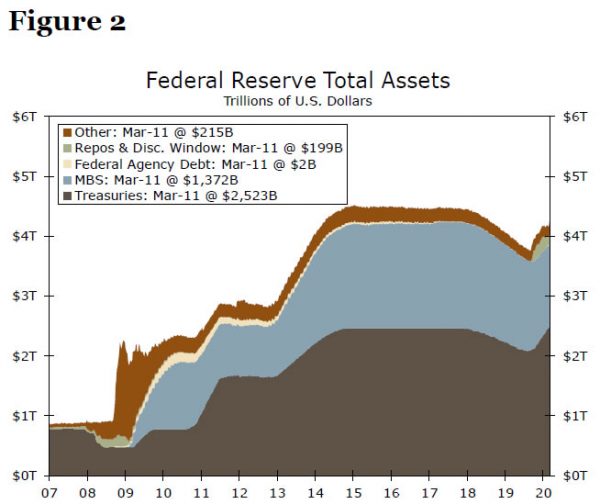

The Federal Reserve also embarked on a program of quantitative easing (QE). Between the fall of 2008 and mid-2014 the Fed’s balance sheet mushroomed to more than $4.5 trillion from less than $1 trillion as it purchased about $2 trillion of U.S. Treasury securities and $1.8 trillion of mortgagebacked securities (Figure 2). The purchases of Treasury securities were meant to bring the long end of the U.S. yield curve lower, which supports lower borrowing costs for businesses and households, and purchases of MBS were intended to breathe life back into the moribund housing market, which essentially collapsed during the financial crisis.

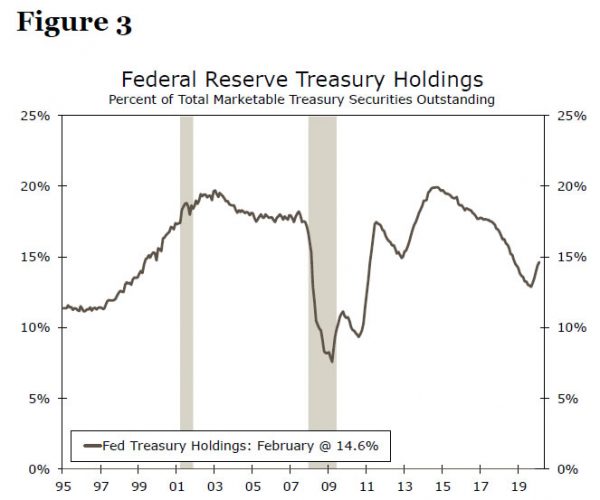

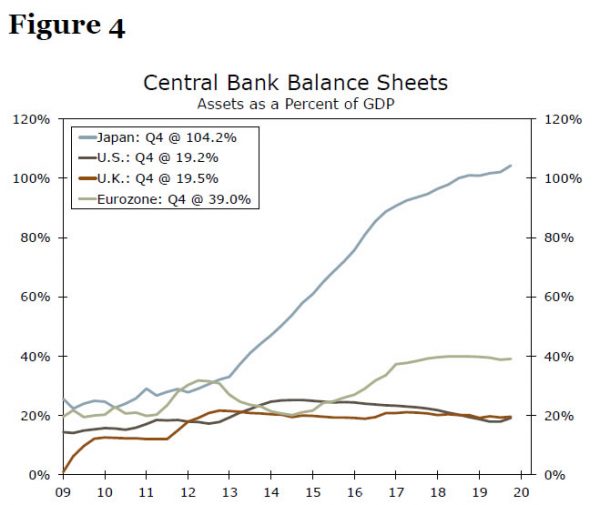

More recently, the FOMC has returned to QE, announcing on March 15 that it will buy $500 billion of Treasury securities and $200 billion of MBS “in the coming months.” In our view, the Fed could certainly expand these purchases either in duration or size. At present, the Fed’s holdings of Treasury securities as a share of the total market is relatively in line with history (Figure 3). And compared to some other developed market counterparts, the size of the Fed’s balance sheet as a percent of GDP is still fairly small, at least on a relative basis (Figure 4). In our view, however, QE purchases of Treasury securities and MBS may not be quite as effective as they were a decade ago. The yield on the benchmark 10-year Treasury security has already plunged to less than 1.00%. How much lower could it go?

Is a Negative Fed Funds Rate an Option?

Of course, the yield on the 10-year German government bond is nearing -1.00%. But the European Central Bank has cut one of its main policy rates to -0.50%. Money market funds (MMFs) play an instrumental role in the financial system of the United States, whereas MMFs are not as crucial in European financial markets. Negative short-term instrument rates in the United States could lead to extreme difficulties with MMFs, with potentially adverse consequences for the U.S. financial system. The minutes of the October 2019 FOMC meeting showed that all members (emphasis ours) “judged that negative interest rates currently did not appear to be an attractive monetary policy tool in the United States.” Chairman Powell reinforced this message on the March 15 conference call, stating in response to a question from a reporter that “We do not see negative policy rates as likely to be an appropriate policy response here in the United States.” Although we would hesitate to say it is impossible, the likelihood of the FOMC taking the fed funds rate negative is quite low, in our view.

Reviving the Emergency Lending Programs of 2008-2009

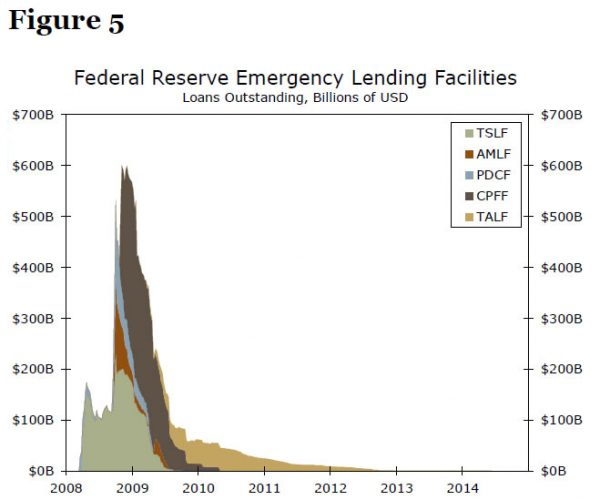

During the financial crisis the Federal Reserve created an alphabet soup-like plethora of lending facilities, and it is starting to reinstate some of these programs. The Fed created the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) in October 2008, and it reinstated the program on March 17 in an effort to relieve strains in the commercial paper market. During the last crisis, the Federal Reserve lent money to a special limited liability corporation (called CPFF LLC) which used the funds to purchase commercial paper directly from eligible issuers. As can be seen in Figure 5, the CPFF was one of the most highly utilized emergency lending programs during the financial crisis, peaking at nearly $350 billion in January 2009. The new CPFF will last for one year, and will once again purchase commercial paper through a special purpose vehicle rather than open market operations.

The Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) is another program that the Fed created during the financial crisis and brought back to life on March 17. Primary dealers can pledge a wide range of securities as collateral in return for borrowing at low interest rates from the Fed.1 The purpose of the PDCF is “to support the credit needs of American households and businesses,” and it serves as a de facto discount window for the primary dealers. It will exist for at least the next six months. The resurrection of the CPFF and the PDCF are strong indications that the Fed’s emergency lending powers remain robust.

Some of the other emergency lending programs that the Fed created during the financial crisis were aimed at providing liquidity in money markets, which is an important cog in the American financial system. Under the Asset-Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (AMLF), the Federal Reserve provided nonrecourse loans to banks, which then used the funding to purchase eligible asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) from money market mutual funds. There was also the money market investor funding facility (MMIFF), which the Fed created to lend directly to money market mutual funds, should they face abrupt withdrawals from investors. The term securities lending facility (TSLF) helped to alleviate funding pressures facing primary dealers by allowing them to pay a fee and, through an auction process, borrow Treasury securities in exchange for eligible collateral consisting of other, less liquid securities.

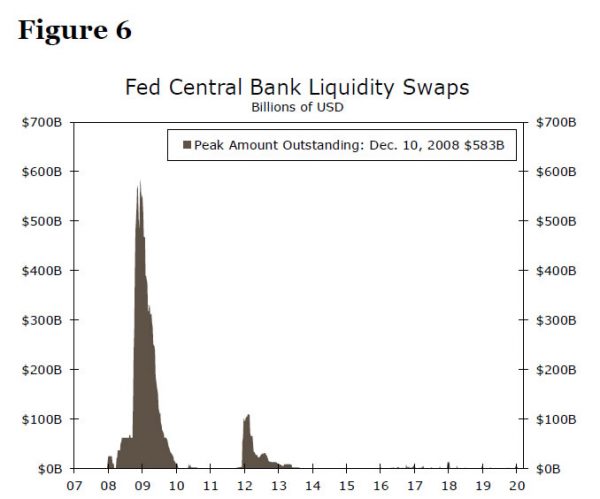

Stresses in U.S. financial markets can also emanate from abroad because the U.S. dollar is the world’s principal reserve currency and foreigners own significant amounts of dollar-denominated securities. During the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve, in coordination with other foreign central banks, aggressively employed its swap lines. These swap line allow foreign central banks to borrow dollars from the Fed, via “loans” of foreign currency to the Federal Reserve, and then lend these dollars to banks in their home countries to help those banks fund their dollar-denominated assets (Figure 6). On March 15, the Fed announced renewed action along these lines to provide additional dollar liquidity. Specifically, the Fed reduced its swap line borrowing rate by 25 bps. The rate now stands at the U.S. dollar overnight index swap (OIS) rate plus 25 bps. In addition, the FOMC announced that foreign central banks could borrow for 84 days, which will supplement the one-week operations that are currently in place.

Could the Federal Reserve bring back some of the other programs and/or create new ones in an effort to combat current financial market strains? Broadly speaking, we believe the answer is yes, and the recent resurrection of some of the aforementioned programs is strong evidence that the Fed’s emergency lending powers remain robust. But, there are still some limitations with which the central bank may need to cope, barring a change in the law. Legislation enacted in the wake of the Great Recession limited some of the Federal Reserve’s emergency lending powers. Specifically, the Dodd-Frank legislation requires that any emergency lending programs maintain “broad-based eligibility” and forbids a “program or facility that is structured to remove assets from the balance sheet of a single and specific company.” This suggests to us that a Maiden Lane style program that is designed to aid an individual firm may no longer be viable. The law also requires that 13(3) emergency lending receive the prior approval of the Secretary of the Treasury, as well as be terminated in a “timely and orderly fashion.”2

Although these hurdles are less serious, they do create additional hoops through which the Fed needs to jump when activating its 13(3) emergency lending powers. Unlike the QE purchases the Fed conducted during this period, most of the emergency lending programs were wound down within one to two years of creation. The CPFF program, for example, lasted from October 2008 to February 2010, while the second biggest facility, TSLF, lasted from March 2008 to February 2010.

What about QE for other Assets, such as Corporate/Municipal Bonds?

Another question we have fielded repeatedly has been whether the Fed may be able to expand its QE purchases to other assets, such as corporate bonds. Under section 14(2) of the Federal Reserve Act (FRA), the FOMC is granted the authority to “buy and sell in the open market…any obligation which is a direct obligation of, or fully guaranteed as to principal and interest by, any agency of the United States.” In practice, this means that when the Fed is conducting open market operations, it is limited to purchasing government-backed securities like Treasuries and agency MBS. Fed officials have signaled that, in order for the Fed to purchase other securities via its standard open market operations, it would require a change in the law by Congress.3

What the Fed could potentially do, however, is buy short-dated municipal debt, specifically debt with a maturity of six months or less, a power granted to it in the same 14(2) section of the FRA. State and local governments are likely to face significant strains in the months ahead as demands on the spending side explode and revenues from sales taxes and other sources dry up. The Fed could help alleviate this strain by buying up much of the debt that will be needed to meet the needs of state and local governments. The Federal Reserve has held these types of assets on its balance sheet before, though admittedly in much smaller size. In 1933 during the Great Depression, the Fed held about $1.5 million in municipal warrants, up from $127,000 in 1927.4 That said, this $1.5 million in municipal holdings in 1933 represented just 0.02% of the Federal Reserve’s total assets.

At present, our municipal bond analysts estimate that there is roughly $120 billion outstanding in fixed-rate municipal debt with maturities of six months or less. Explicit coordination between the Fed and fiscal agents is generally frowned upon as a violation of the central bank’s independence. But, sometimes desperate times call for desperate measures. So perhaps if the Fed began to buy some of this debt with a large and open-ended commitment, state and local governments would take the hint and begin to issue short-dated debt in much larger amounts.

Conclusion: Ammo Running Low, but Not Gone

With the fed funds rate now back to a target range of 0.00-0.25%, the Federal Reserve will need to turn to non-conventional tools to fight the economic and financial market challenges in the months ahead. Fortunately, there is still some ammunition remaining. These options include: forward guidance to signal the fed funds rate will remain at zero for an extended period of time, additional QE purchases of Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the resurrection of several alphabet-soup programs created during the 2008 financial crisis and the expansion of asset purchases into short-dated municipal debt. Although these tools should be helpful in the event of their eventual adoption, they are unlikely to solve the current economic challenges alone. For that, it will likely take a significant fiscal salvo, a topic we explore in a separate piece.

1 The primary dealers are the 24 financial institutions through which the Treasury Department auctions Treasury securities. Wells Fargo is a primary dealer.

2 Labonte, M. & M. Maureen Murphy. (2016). “Federal Reserve Issues Final Rule on Emergency Lending.” Congressional Research Service.

3 For example, see Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President Eric Rosengren’s speech “Observations on Monetary Policy and the Zero Lower Bound.” March 6, 2020.

4 https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/arfr/1930s/arfr_1933.pdf https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/arfr/1920s/arfr_1927.pdf