Summary

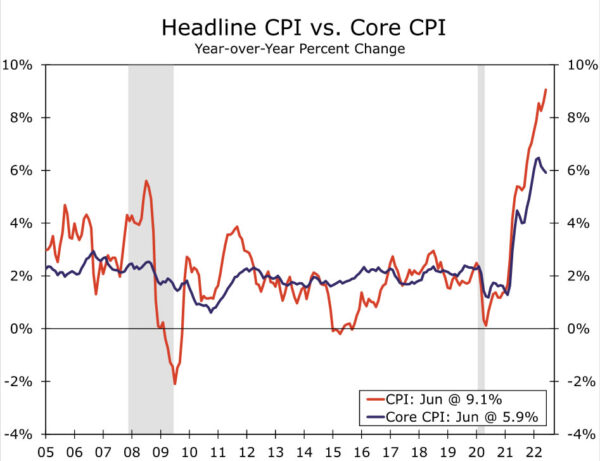

- The FOMC appears poised to raise its target range for the federal funds rate by at least 75 bps at its next meeting on July 27. The 372K increase in nonfarm payrolls in June indicates that the economy is holding up reasonably well at present. Furthermore, inflation remains forefront in the minds of most FOMC members as CPI inflation jumped to 9.1% in June from 8.6% in May.

- The forecast that we published last week, which was made in the immediate aftermath of the higher-than-expected inflation data for June, looks for a 100 bps rate hike on July 27.

- Most Committee members indicate a desire to get the fed funds rate to “neutral” as soon as possible. Many members believe that policy needs to get into “restrictive” territory to wring inflation out of the economy. We reasoned that a 100 bps rate hike would get the fed funds rate to neutral and close to restrictive in an expeditious fashion.

- We think 100 bps will be on the table on July 27, but data on real economic activity in June that were released after we published our forecast make the case for a supersized rate hike less compelling. These data reinforced previously published data that point in the direction of economic deceleration.

- Furthermore, comments by Fed officials at the end of last week suggest that a rate increase of 100 bps may be a bit too aggressive for many FOMC members. Therefore, we acknowledge that the FOMC may indeed opt to raise rates by “only” 75 bps.

- As is customary for the July meeting, an updated Summary of Economic Projections will not be released on July 27. Therefore, the Committee will be limited to the post-meeting statement and Chair Powell’s press conference as mediums through which to express its future policy intentions. We expect that the statement will continue to express concern over inflation, and Chair Powell likely will echo these concerns in his press conference.

- But will the statement and/or Chair Powell make any reference to recent signs of economic deceleration? If so, then the Committee may be signaling that a slower pace of policy tightening may be appropriate in coming meetings.

- With inflation continuing to climb faster than expected, the FOMC remains squarely focused on the price stability side of its mandate. Before taking its foot off the brake, Chair Powell has made clear the Committee will need to see a series of declining inflation readings.

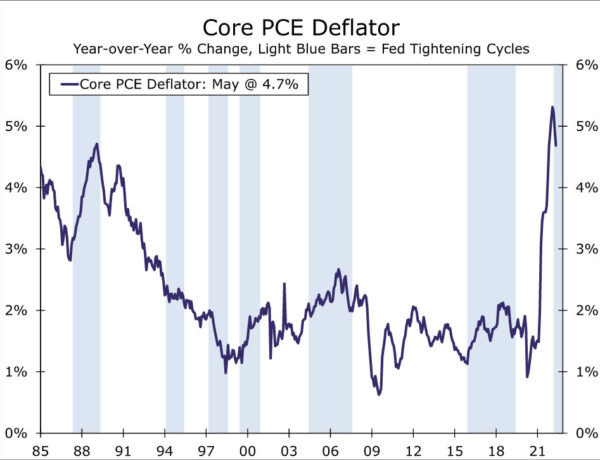

- But once inflation does begin to moderate, how low does the FOMC need to see it go, and at what cost to the labor market, before the Committee stops tightening? Based on prior tightening cycles and the blistering pace of inflation at present, we suspect core PCE inflation would need to slow to at least a 3% pace, even if that brings higher unemployment.

A Supersized 100 bps Rate Hike Will Be on the Table on July 27

At the beginning of the last FOMC “blackout period,” which began on Saturday, June 4, market participants were widely expecting a 50 bps rate hike at the conclusion of the policy meeting on June 15. However, higher-than-expected CPI inflation data for May, which were released on Friday, June 10, changed the narrative. The 1.0% monthly increase in the overall consumer price index pushed the year-over-year rate of CPI inflation up to 8.6%, which was 0.3 percentage points higher than the consensus forecast. In the wake of the hotter-than-expected inflation data, news reports began to circulate that a 75 bps rate hike would be under active consideration at the upcoming FOMC meeting. Market expectations immediately reset, and a few days later the Committee did indeed raise its target range for the federal funds rate by 75 bps.

Another rate hike of at least 75 bps seems like a sure bet for the July 27 FOMC meeting. Nonfarm payrolls rose by 372K in June, which was markedly stronger than the consensus forecast, suggesting that the economy is holding up reasonably well. Moreover, Fed officials seem to be comfortable with another 75 bps rate hike. Federal Reserve Governor Christopher Waller said on July 7 that “I am definitely in support of doing another 75 basis point hike in July.” St. Louis Fed President Bullard, who is a voting member of the Committee this year, stated that a 75 bps rate hike at the upcoming FOMC meeting “would make a lot of sense.” The need to move by at least 75 bps was reinforced by the CPI data for June that printed on July 13. As shown in Figure 1, the CPI shot up another 1.3% in June, pushing the year-over-year rate up to 9.1%. Not only was the headline rate of CPI inflation significantly higher than the consensus forecast, but as we discussed in our write-up of the data, price increases were widespread.

The disturbing price data made Fed officials even more concerned about the inflation outlook. Atlanta Fed President Bostic, who is not a voting member this year but who participates in the Committee’s deliberations, said that “the top-line number is a source of concern.” When asked if the higher-than-expected inflation data could lead the Committee to hike rates by 100 bps on July 27, Bostic replied “everything is in play.” Cleveland Fed President Mester (a voting member this year) characterized the June CPI data as “uniformly bad” and added that she saw no reason for moving less than the Committee did in June when it raised rates by 75 bps. The combination of higher-than-expected inflation and its widespread nature led us to change our forecast of a 75 bps rate hike to 100 bps, which we discussed in more detail in the monthly U.S. Economic Outlook that we published last week.

Most Fed officials have expressed the need to get back to “neutral,” which is the level of the federal funds rate that is neither stimulating the economy nor restraining it, as soon as possible. Although precisely estimating neutral is highly difficult in real time, many FOMC members currently estimate that it is somewhere around 2.50%. Lifting the fed funds rate by 100 bps on July 27 would take the target range to 2.50%-2.75%, which would be in the vicinity of most estimates of neutral. In our view, the higher-than-expected inflation data for June reinforced the need for haste in getting to a neutral policy rate.

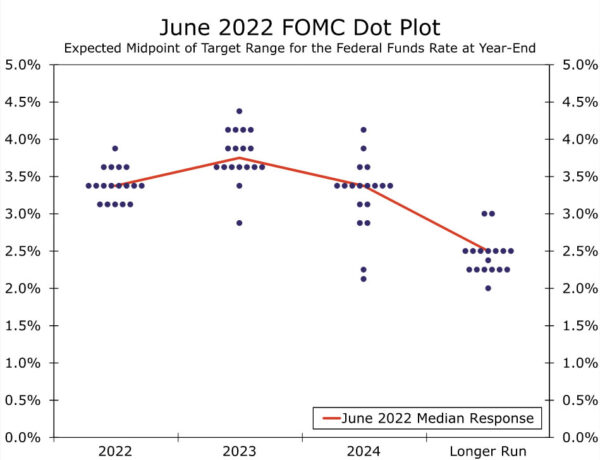

Additionally, many policymakers believe that rates will eventually need to move into “restrictive” territory, which implies further tightening at upcoming FOMC meetings. The dot plot that was released after the June FOMC meeting showed that many Committee members thought that a fed funds target range of 3.25%-3.50% would be appropriate at the end of 2022 with further tightening needed next year (Figure 2). Although a dot plot will not be released following the meeting on July 27, it seems reasonable to us that a more expeditious rise into restrictive territory would be appropriate in light of the recent inflation data.

We believe that a supersized rate hike of 100 bps will be on the table on July 27, but developments since we published our most recent forecast have raised the probability that the Committee opts for a smaller increase of “only” 75 bps. Retail sales in June rose by a strong 1.0% relative to the previous month. But the headline rate was flattered by the sharp increase in good prices in June. On a real basis, retail spending likely edged lower in June. Industrial production declined 0.2% in June relative to the previous month, and May’s increase of 0.2% was revised lower to flat on the month. Long-term inflation expectations as measured in the University of Michigan’s Survey of Consumer Sentiment, which was cited by Chair Powell as a reason for opting for the larger-than-guided 75 bps hike in June, retreated from 3.1% in June to 2.8% in July.

Moreover, official commentary at the end of last week indicates that many FOMC members seem to think that a rate increase of 100 bps may be a bit too aggressive. Atlanta Fed President Bostic walked back his previous comments by suggesting that he would not favor a 100 bps rate increase. Governor Waller left the door open to a 100 bps rate hike but indicated that he favors 75 bps, while St. Louis Fed President Bullard also played down the notion of an increase of 100 bps. As of this writing, markets are priced for a 20% probability of a 100 bps increase and an 80% probability of a 75 bps rate hike. But news stories during the last blackout period re-calibrated market expectations for the outcome of the June FOMC meeting. Market participants will be on high alert in the days ahead for news stories that are meant to guide expectations ahead of the July 27 policy meeting.

How Will the FOMC Characterize the State of the Economy?

The FOMC releases its Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), in which it summarizes its macroeconomic forecasts, four times a year: March, June, September and December. Because a SEP will not be released on July 27, the Committee will be limited to its post-meeting statement and to Chair Powell’s press conference as mediums through which it can signal its future policy intentions. Inflation was largely the focus of the statement that was issued at the conclusion of the June 15 FOMC meeting. Specifically, the statement noted that “the Committee is highly attentive to inflation risks.” In contrast, policymakers did not appear to be overly concerned about economic growth, noting that “overall economic activity appears to have picked up after edging down in the first quarter.”

We expect inflation will remain the focus of the post-meeting statement on July 27, and Chair Powell likely will stress during his press conference that the Committee remains committed to meeting its 2% inflation target “over the longer run.” But will the statement, as well as Chair Powell, make any reference to signs of slower growth?

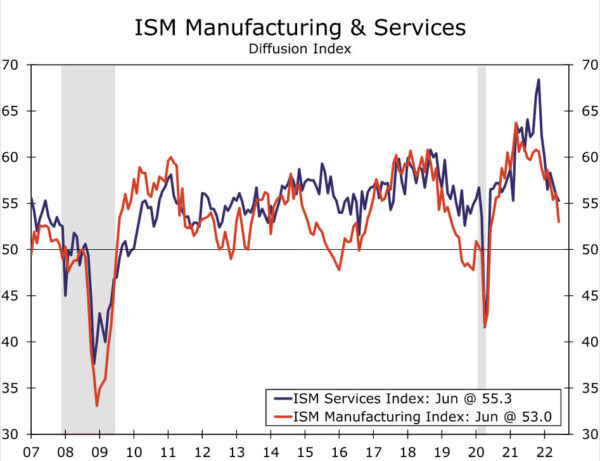

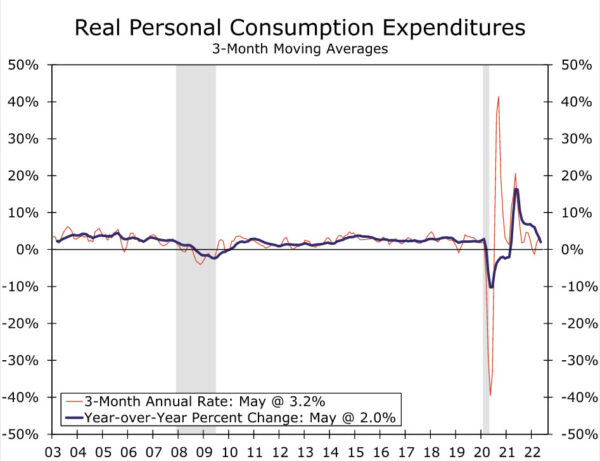

The 372K jobs that were created in June suggest that the economy is holding up reasonably well at present. But as discussed previously, there have also been some unmistakable signs of economic deceleration. In addition to the indicators noted above, the ISM indicies for the manufacturing and service sectors have both receded in recent months, although both remain above 50, which is the demarcation separating expansion from contraction (Figure 3). Real consumer spending has decelerated sharply in recent months (Figure 4), and consumer confidence has taken a nosedive. The headline rate of real GDP growth likely was sluggish and may even have been negative again in the second quarter. Will signs of slowing economic growth be noted more in the statement following the July 27 meeting than they were on June 15? If they are, then the Committee may be signaling that a slower pace of tightening may be appropriate at upcoming meetings. But even if the FOMC opts to raise rates by 75 bps in July and then downshifts to 50 bps in September, it would still represent a remarkably aggressive pace of rate hikes since March, exemplifying the seriousness with which the FOMC is approaching the inflation problem.

Searching for Reaction Function Clues

The Federal Reserve is tasked with achieving the two goals of its dual mandate: full employment and price stability. Both of these goals are paramount for monetary policymakers. But, depending on macroeconomic conditions, FOMC officials may focus more on one half of the mandate when making policy decisions at any given time. For example, when the COVID-19 pandemic first struck the United States and the unemployment rate skyrocketed to levels not seen since the Great Depression, the Federal Reserve took unprecedented steps to support the economy and labor market. In other words, the FOMC seemed to be putting more weight on the employment part of its mandate than on the inflation part. More recently, historically high inflation has pushed FOMC officials to tighten monetary policy aggressively and with a fervor that has not been seen in decades. It seems as if the Committee is focused almost entirely on its inflation mandate at present.

Of course, over the longer-run the two prongs of the mandate are in harmony. Longer-run price stability is key to longer-run full employment and vice versa. But, as John Maynard Keynes famously said, “in the long-run we are all dead,” and achieving the correct policy prescription in real time is highly difficult. To that point, it has been remarkable how much consensus there has been among FOMC participants in recent months given this rapid shift in Fed policy. As recently as early March the federal funds rate was near 0% and asset purchases were just coming to a close. Fast-forward a bit more than four months and quantitative tightening is underway and the federal funds target range is poised to be 2.25%-2.50% if the FOMC hikes by 75 bps, or 2.50%-2.75% if it chooses a more aggressive 100 bps rate increase.

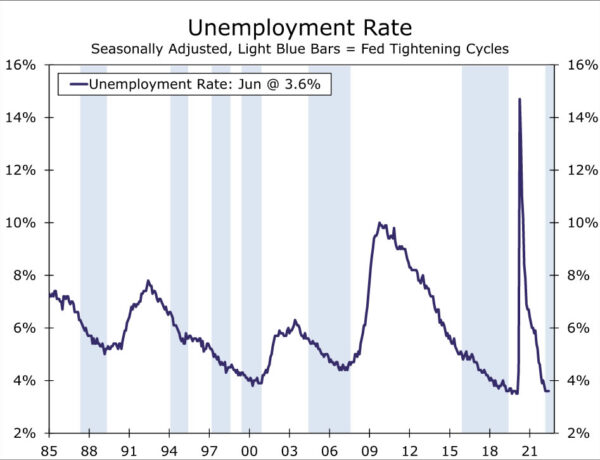

The relative harmony among FOMC participants over the past few months makes more sense when viewed through the lens of macroeconomic conditions and the current stance of monetary policy. The unemployment rate has remained exceptionally low in recent months, employment growth has been robust and CPI inflation touched yet another cycle-high in July. Against this backdrop, the case for moving monetary policy away from its highly accommodative stance has been a fairly straightforward one. Put another way, everyone is a hawk when inflation is running at 9%, the unemployment rate remains near a five-decade low and the effective federal funds rate is still well below most estimates of “neutral.” However, moving forward we expect the FOMC to face an increasingly difficult task, and this in turn could lead to a more nuanced reaction function. Quashing elevated inflation clearly remains the top priority before the FOMC. But, just how far into restrictive territory does the federal funds rate need to go to achieve that goal? And at what cost to the labor market?

Before taking its foot up off the brake, the Fed will need to see a moderation in actual inflation. At Chair Powell’s last post-meeting press conference, he shared that the Committee would like to see “compelling evidence” that inflation is slowing in the form of a “series of declining monthly” rates. That directional shift has yet to start, let alone cement itself. Once it does, we suspect the FOMC will tighten policy more slowly given that policy would likely already be in restrictive territory and officials will presumably want to see how the medicine is taking. However, we believe it will take more than just directional improvement in inflation for the Fed to stop tightening altogether given the elevated starting point.

Since the fed funds rate became the primary tool of FOMC policy, the Committee has stopped tightening when the unemployment rate stopped falling (Figure 5) or, as in the case of the 1997-1998 and 2015-2018 cycles, core PCE inflation was generally below the 2% target (Figure 6). But inflation was significantly lower in those periods while the unemployment rate was significantly higher. We therefore expect the Fed to accept more pain in the labor market than prior tightening cycles. Fed officials increasingly appear to have the stomach for some deterioration in the labor market. In the most recent SEP, the median estimate among FOMC officials saw the unemployment rate rising above 4% after taking the policy rate into restrictive territory. With core inflation remaining below 3% in each of the tightening cycles since the 1990s, we suspect the FOMC will not be comfortable calling it quits with rate hikes until inflation has slowed to around a 3% pace. If the labor market continues to hang in there and the unemployment rate remains within the FOMC’s longer run central tendency range of 3.5%-4.2%, the FOMC could press further ahead in an effort to insure inflation does not flare up again.

The FOMC looks set to get some help on headline inflation soon as commodity prices fall. However, we suspect a series of slower monthly core readings would be more compelling evidence that inflation is on a sustainable downward trend given the volatility that surrounds energy and food commodities in today’s fraught geopolitical and physical climate. The composition of core inflation is also likely to play a role in the Fed’s thinking. The largest components of the core index, primary rent and owners’ equivalent rent, have notoriously long lags with housing market conditions. Therefore, the Fed may narrow in even further to core-ex-shelter inflation if private sector measures of housing costs show softening prices that will take a few quarters to appear in the official inflation measures. While the more nuanced cuts of inflation data are likely to be tricky to communicate at such a delicate time in the economy, a slowdown in the right components could accelerate the rate at which the Fed’s focus shifts back to the labor market.