Summary

- We expect the FOMC to announce another 25 bps rate cut at the conclusion of its meeting on October 29. The government shutdown has clouded the U.S. economic outlook as most government data releases are currently delayed. The limited data that have been released suggest that gradual labor market softening has continued alongside inflation that is running at roughly a 3% underlying pace.

- We believe the shutdown is having a small but negative impact on the U.S. economy. The rule-of-thumb that each week of the shutdown shaves off 0.1-0.2 percentage points of quarterly economic growth still strikes us as reasonable. Most—though not all—of this output should be recouped in Q1, assuming that the shutdown has ended by then. If the shutdown drags on much longer, key economic data covering the month of October may be outright skipped rather than merely delayed, making it harder for policymakers to assess the state of the economy in real-time.

- Against this backdrop, several key FOMC officials have signaled support for another rate cut in October. However, public comments from FOMC officials generally have been careful to acknowledge that rate cuts past October are not guaranteed.

- We do not expect any major changes to the language in the post-meeting policy statement and expect Chair Powell’s press conference remarks to echo the sentiment from his public remarks on October 14: inching toward neutral, but cognizant of the two-sided risks to the outlook given the current tension between their employment and inflation goals. There will not be an update to the Summary of Economic Projections at this meeting.

- Changes to the Fed’s balance sheet runoff program also appear to be coming soon. Chair Powell suggested that runoff may end in the “coming months” in a recent speech. A wide range of indicators suggest this would be a prudent move, in our view. There has been a firming in repo rates recently in a sign that bank reserves are closer to ample than abundant. Furthermore, key thresholds have been reached or are close to being hit for the reserves-to-GDP rand reserves-to-bank assets ratios.

- Our longstanding forecast has been that the FOMC would announce the end of QT at its meeting on December 9-10, with balance sheet shrinkage ceasing after December 31. We are sticking with that forecast as a base case, although we acknowledge that it is a close call and the Committee may opt to end QT at the October meeting.

- If QT runs through year-end, the Fed’s balance sheet will have declined by just shy of $2.5 trillion from its peak in the spring of 2022. We estimate the reduction in the central bank’s security holdings has exerted 25-50 bps of upward pressure on long-term interest rates.

- Note that even if aggregate balance sheet runoff ceases, that does not mean that balance sheet policy has shifted to neutral. If the Fed’s balance sheet is held flat for a couple quarters, then it will still be shrinking as a share of GDP. Furthermore, the composition of the balance sheet can continue to evolve such that policy accommodation is still being removed. We look for MBS runoff to continue indefinitely, with these securities replaced one-for-one with Treasury bills. If realized, this would gradually reduce support to the mortgage market from the Fed’s balance sheet and put some very modest upward pressure on longer-term yields, all else equal.

Another Cut Coming in October

It has been a strange five weeks since the FOMC last met on September 17. At that meeting, the FOMC reduced the federal funds rate by 25 bps—its first rate move since December 2024. The dot plot showed a median projection of two more 25 bps rate cuts by year-end, although it was a close call; nine of the 19 participants looked for one or zero rate cuts at the final two meetings of the year. Shortly thereafter, the federal government shut down on October 1, and this created an economic data vacuum. The September employment report, scheduled to be released on October 3, has been indefinitely delayed. Many other key data releases, from housing starts to job openings to retail sales, have been delayed as well.

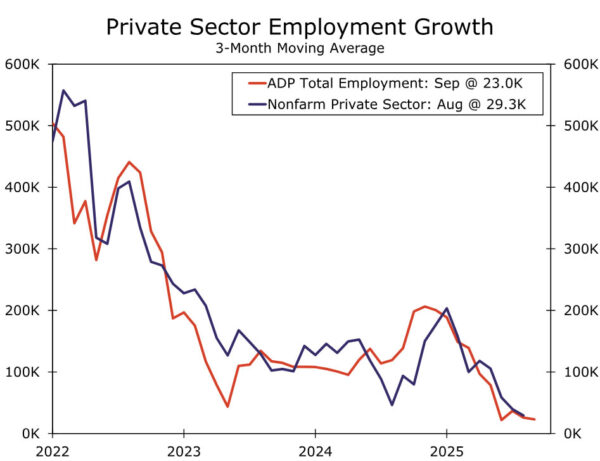

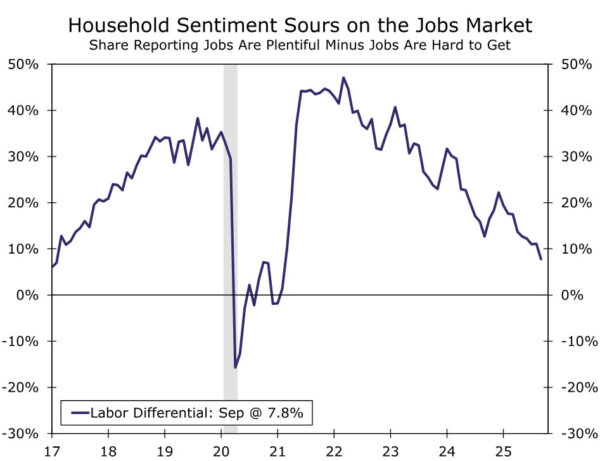

The limited data that we have received since the FOMC’s last meeting suggest that the macro trends that were in place before the shutdown are still entrenched. The labor market news has been consistent with further gradual softening. ADP’s measure of total private sector employment declined by 32K in September, the weakest reading since March 2023. With August’s downwardly-revised ADP reading now sitting at -3K, the three-month moving average has fallen to just 23K (Figure 1), and monthly job growth has posted back-to-back negative readings for the first time since 2020. The Chicago Fed’s Labor Market Indicators release estimated the September unemployment rate at 4.34%, a couple basis points above the actual reading in August. Encouragingly, state level data on initial jobless claims suggest layoffs have been relatively flat in recent weeks, but household sentiment about job availability deteriorated further last month (Figure 2).

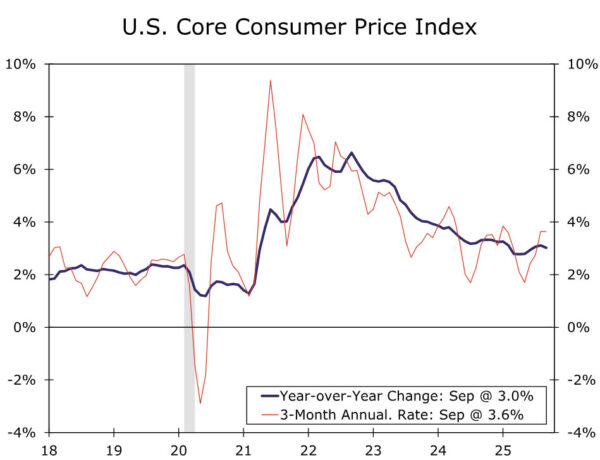

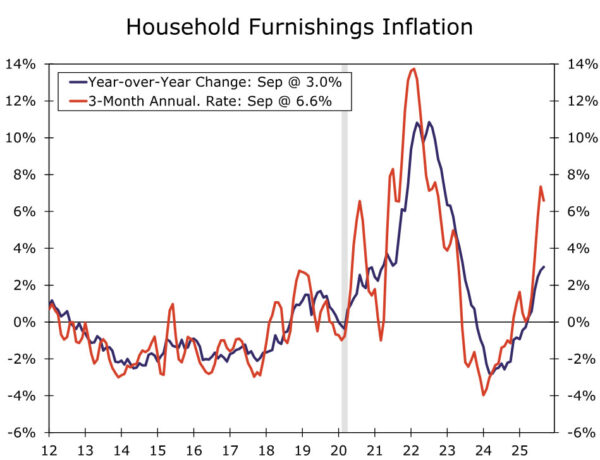

On the inflation front, the September CPI report was released on October 24, nine days after its originally scheduled date. The catalyst to publish the September CPI stemmed from the need for the Social Security Administration to prepare the annual cost of living adjustment for beneficiaries. Because data collection for the September CPI had largely been completed before the shutdown began on October 1, the BLS was able to compile and release the report. It showed inflation that remains uncomfortably above the central bank’s target. Headline CPI rose 3.0% year-over-year, the highest since January. The core CPI ebbed to 3.0% year-over-year, but the hotter 3.6% three-month annualized rate signals that prices accelerated in the third quarter (Figure 3). Higher prices continue to flow through to many tariff-related items in a sign that the price pressures from this year’s new import duties are still making their way into the economy (Figure 4).

Beyond the data implications, we believe the shutdown is having a small but negative impact on the U.S. economy. At least 700K federal government workers have been furloughed without pay, while the remainder of the 2.3 million federal civilian workforce is still working—although also without pay. The rule-of-thumb that each week of the shutdown shaves off 0.1-0.2 percentage points of quarterly economic growth still strikes us as reasonable. Most—though not all—of this output should be recouped in Q1, assuming that the shutdown has ended by then. For further reading on the shutdown’s impact, see our recent special report.

Against this backdrop, FOMC participants generally have signaled support for another 25 bps rate cut at the October meeting. Speaking on October 14, Chair Powell stated that “the outlook for employment and inflation does not appear to have changed much since our September meeting four weeks ago.” Governor Waller stated in a speech on October 16 that he supports a 25 bps rate cut to support the labor market. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President and current FOMC voter Susan Collins shared her view that “with inflation risks somewhat more contained, but greater downside risks to employment, it seems prudent to normalize policy a bit further this year to support the labor market.” Comments from newly-appointed Governor Miran suggests he will once again vote for a 50 bps rate cut at the upcoming meeting. However, the public comments from FOMC officials generally have been careful to acknowledge that rate cuts past October are not guaranteed. A case in point: Governor Waller’s October 16 talk was titled “Cutting Rates in the Face of Conflicting Data,” a nod to the softer labor market, stronger real GDP growth and above-target inflation regime in which the FOMC finds itself.

Our expectation is that the FOMC will cut the federal funds rate by 25 bps at the October meeting. We do not expect any major changes to the language in the post-meeting policy statement, and in the press conference, we expect Chair Powell’s remarks to echo the sentiment from his public remarks on October 14: inching toward neutral, but cognizant of the two-sided risks to the outlook given the current tension between their employment and inflation goals. Beyond October, we look for another 25 bps rate cut at the December meeting, and then we expect the FOMC to move to an every-other-meeting approach for rate cuts. We project two more 25 bps rate cuts in March and June 2026, followed by a long hold at 3.00%-3.25% for the federal funds rate.

QT Is Nearing the Finish Line

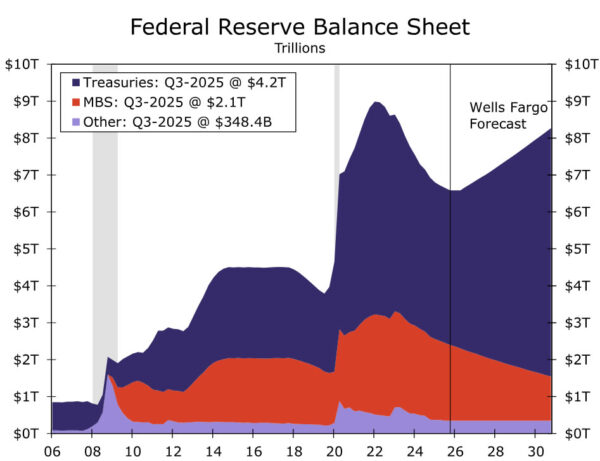

Changes to the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet runoff program appear to be coming soon. At present, the Federal Reserve is reducing the size of its balance sheet through passive runoff, commonly referred to as quantitative tightening (QT). Treasury security runoff is subject to a cap of $5 billion per month, while mortgage-backed security (MBS) runoff is subject to a cap of $35 billion per month. In practice, MBS runoff has been averaging roughly $17 billion per month, so total QT has been a bit more than $20 billion per month on average.

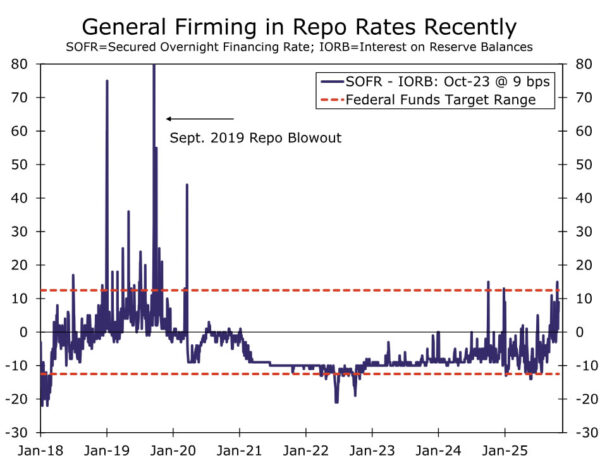

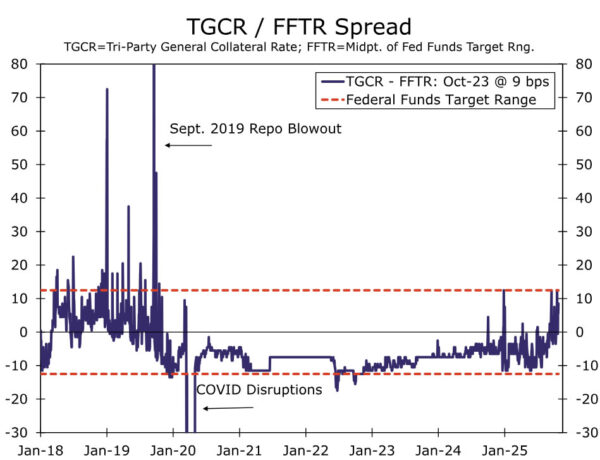

The core of Chair Powell’s October 14 speech was focused on the outlook for the balance sheet. In Chair Powell’s words, the Fed’s “long-stated plan is to stop balance sheet runoff when reserves are somewhat above the level we judge consistent with ample reserve conditions. We may approach that point in coming months, and we are closely monitoring a wide range of indicators to inform this decision.” A wide range of evidence has begun to build that bank reserves are closer to ample than abundant. There has been a general firming in repo rates since the end of the summer, with SOFR trading comfortably above IORB and the tri-party general collateral rate (TGCR) testing the upper-bound of the fed funds target range (Figures 5 and 6). It was the latter rate that Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas President Lorie Logan recently suggested as a future replacement for the federal funds rate as the central bank’s target interest rate.

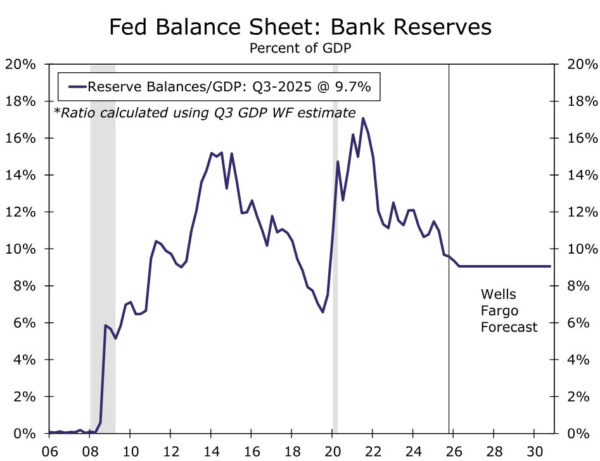

Looking beyond the recent moves in money market rates, past research on this topic also points to reserves becoming less abundant, even if they are not yet scarce. In a speech given on July 10, Governor Waller cited a bank reserves-to-GDP ratio of 9% as “the threshold below which reserves would not be ample.” We estimate this ratio was 9.7% at the end of Q3, so not quite to Governor Waller’s yardstick, but getting close. Research co-authored by Federal Reserve Bank of New York President John Williams cites a reserves-to-bank assets ratio of 12%-13% as another key threshold to monitor, and this level has been approximately reached.1

Our longstanding forecast has been that the FOMC would announce the end of QT at its meeting on December 9-10, with balance sheet shrinkage ceasing after December 31. We are sticking with that forecast as a base case, although we acknowledge that it is a close call and the Committee may opt to end QT at the October meeting. Although there has been some unexpected pressure and volatility in repo markets recently, it generally has been more mild than what occurred on the worst days of 2019 even when excluding the September repo blowup of that year (refer back to Figures 5 and 6). The Standing Repo Facility (SRF) is also in place to serve as a backstop (albeit an imperfect one) to the market which was not the case in 2019. Chair Powell’s remarks on October 14 that QT may end in the “coming months” do not necessarily point to an immediate end to balance sheet runoff. Furthermore, we suspect the Committee will want to take a meeting to discuss what comes next for the balance sheet regarding its security composition.

If QT runs through year-end, the Fed’s balance sheet will have declined by just shy of $2.5 trillion from its peak in the spring of 2022, a reduction in the central bank’s security holdings that we estimate has exerted 25-50 bps of upward pressure on long-term interest rates.2 Note that even if aggregate balance sheet runoff ceases, that does not mean that balance sheet policy has shifted to neutral. If the Fed’s balance sheet is held flat for an extended period of time, then it will still be shrinking as a share of GDP. Bank reserves will continue to decline gradually and in proportion to the growth in non-reserve liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet, such as currency in circulation.

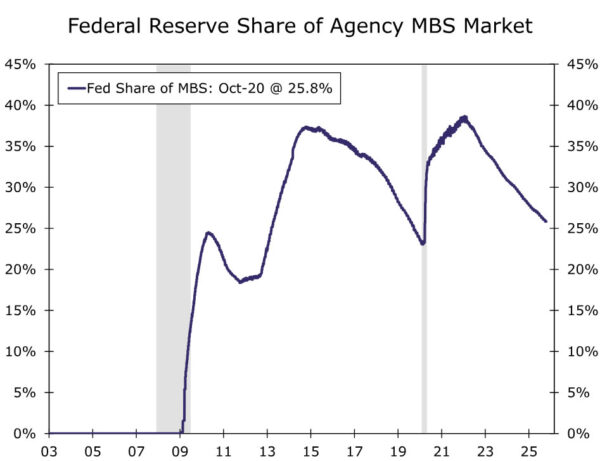

Furthermore, the composition of the balance sheet can continue to evolve such that policy accommodation is still being removed. We look for MBS runoff to continue indefinitely as the Federal Reserve strives to reduce its mortgage holdings and slowly return to holding primarily Treasury securities. In order to keep the total size of the balance sheet unchanged amid ongoing MBS runoff, we look for the Federal Reserve to start buying Treasury securities such that they replace MBS paydowns one-for-one. Returning to a primarily Treasury security portfolio would reduce the support that the central bank lends to the mortgage market. The Federal Reserve’s share of the agency MBS market has not been below 20% since the early 2010s, but this should be within reach in a few years if MBS runoff continues (Figure 9).

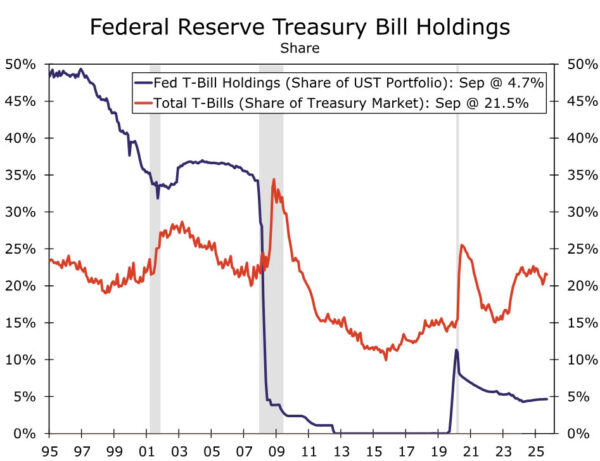

Another factor to consider is the weighted-average maturity of the central bank’s Treasury security holdings. At present, the Federal Reserve’s security holdings generally skew longer-dated than the overall Treasury market. The Federal Reserve T-bill holdings comprise just 5% of its Treasury security holdings despite T-bills accounting for roughly 22% of the overall Treasury market (Figure 10). Our base case is that the Federal Reserve will purchase Treasury bills to replace MBS as holdings of the latter continue to decline. Slowly replacing MBS with T-bills would reweight the Fed’s balance sheet away from longer-dated securities and toward shorter-dated securities, putting some very modest upward pressure on longer-term yields, all else equal.

Endnotes

1 – Afonso, Gara, Domenico Giannone, Gabriele La Spada and John C. Williams. May 2025. “Scarce, Abundant, or Ample? A Time-Varying Model of the Reserve Demand Curve.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

2 – Federal Reserve Bank of New York, March 2024. Survey of Primary Dealers; Crawley, Edmund, Etienne Gagnon, James Hebden and James Trevino. June 2022. “Substitutability between Balance Sheet Reductions and Policy Rate Hikes: Some Illustrations and a Discussion.” Federal Reserve Board; Wei, Bin. July 2022. “How Many Rate Hikes Does Quantitative Tightening Equal?” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta; Gulati, Chaitri and A. Lee Smith. November 2022. “The Evolving Role of the Fed’s Balance Sheet: Effects and Challenges.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.