Summary

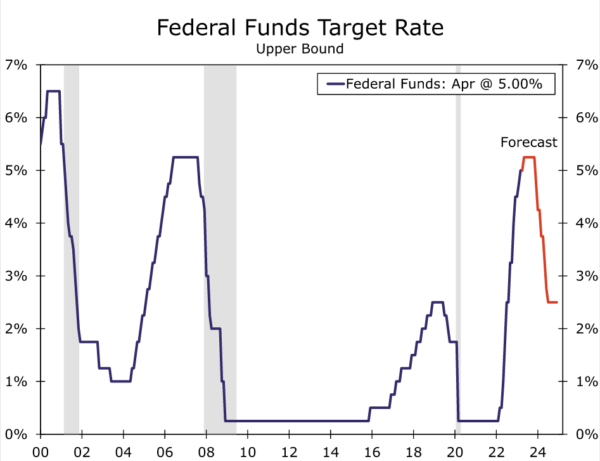

- We expect the FOMC to raise the target range for the fed funds rate by 25 bps on May 3, bringing it up to 5.00%-5.25% from 0.00%-0.25% only 14 months ago. We also anticipate that the Committee will continue quantitative tightening (QT) at its current pace.

- Stress in the financial system related to the failure of two regional banks in early March has eased over the inter-meeting period, alleviating concerns over a rapid tightening in credit conditions. The jobs market is cooling only gradually, and the unemployment rate is still near historic lows. The trend in inflation remains uncomfortably high, as evidenced by core CPI advancing at a 5.1% clip over the past three months.

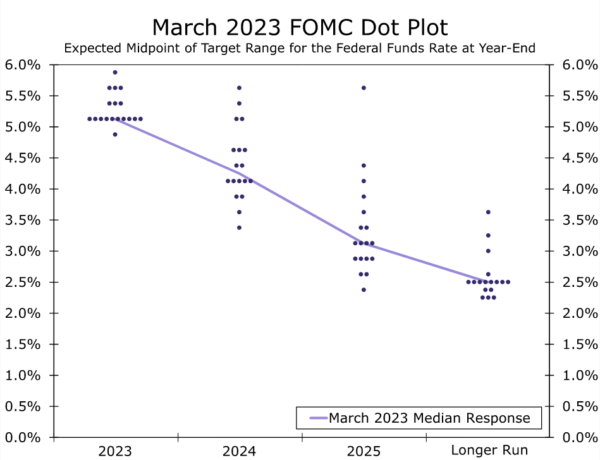

- However, we believe the statement and press conference likely will signal that May’s hike may very well be the last of this tightening cycle. In March, the so-called “dot plot” showed that 11 of the Committee’s 18 participants viewed a fed funds rate of 5.00%-5.25% or lower at year-end 2023 as the most likely outcome, a view that has not seemed to have been swayed by the latest data.

- If most officials see the May meeting as likely to be the final hike this cycle, then we would expect the statement to no longer include the phrase that “some additional policy firming may be appropriate.”

- That said, we do not think the statement will fully close the door on further rate hikes, given that inflation remains well above target. Rather, the statement likely will include an acknowledgement that further adjustments in rates are possible. The outlook will be based on the Committee’s assessment of cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags of policy on economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.

- If, as we expect, the statement signals that additional increases are less likely, but not fully off the table, then dissents among voting participants are likely to be avoided.

- We do not think a technical tweak to the Fed’s overnight repurchase agreement (RRP) facility is forthcoming, and in the final section of this report, we dive deeper into this tool in the central bank’s toolkit.

We Look for the FOMC to Hike Rates by 25 bps on May 3

In light of the volatility that swept through financial markets only a month or so ago following the failure of two regional banks, market participants eagerly await the outcome of the next meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) on May 3. Actions taken by the Federal Reserve, the Treasury Department and the FDIC following the collapse of these regional banks appear to have stabilized financial markets. Major equity indices have trended higher over the past month, and credit spreads have generally narrowed. Unless turmoil were to grip the nation’s banking system anew in coming days, we look for the Committee to raise its target range for the federal funds rate by another 25 bps on May 3. If the Committee does indeed hike rates by 25 bps, then it will have increased its target range by 500 bps since March 2022.

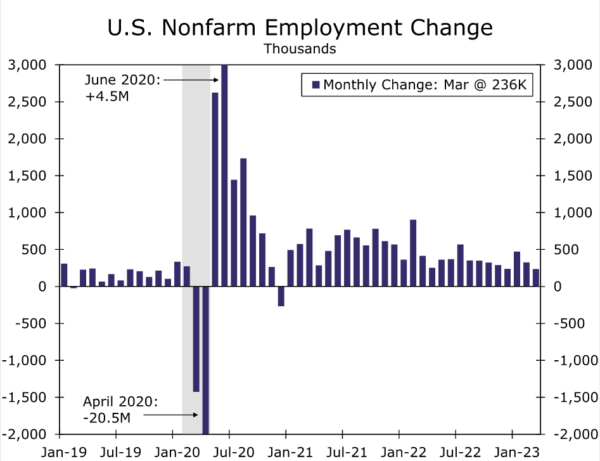

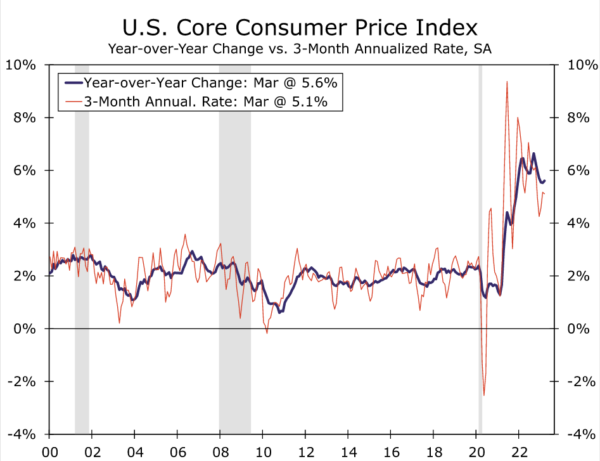

In our view, most FOMC members will support another 25 bps rate hike due to the aforementioned stability in financial markets and recent economic data indicating that the labor market remains strong and inflationary pressures are still acute. Data released on April 7 showed that employment rose by 236K in March (Figure 1). Although this was the smallest monthly increase in nonfarm payrolls in more than two years, it still exceeded the average gain of roughly 185K per month during the 2010s expansion. The unemployment rate ticked down to 3.5% from 3.6% in February, suggesting that the labor market generally remains tight. Overly tight labor markets could keep wage growth above what would be consistent with 2% inflation. In that regard, core CPI inflation, which printed at a year-over-year rate of 5.6% in March, remains elevated (Figure 2). Furthermore, consumer prices excluding food and energy rose at an annualized rate of 5.1% between December and March, indicating that core inflation over the past few months has only been incrementally slower than core inflation over the past year.

Reading the Tea Leaves in the Post-Meeting Statement

Market participants undoubtedly will parse the post-meeting statement for clues about the outlook for monetary policy in coming months. The statement on March 22 addressed the turmoil in the banking system by noting “recent developments are likely to result in tighter credit conditions for households and businesses and to weigh on economic activity, hiring, and inflation.” But the statement also acknowledged that “the extent of these effects is uncertain.” Although the situation in the banking system seems more stable today than it did on March 22, we think the FOMC will want to continue highlighting the heightened degree of uncertainty that surrounds the economic outlook at this time.

More important, we think that the FOMC will opt to change its “forward guidance” regarding the outlook for monetary policy. When the current tightening cycle commenced in March 2022, the FOMC stated it “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate,” and it continued to use this phrase in every post-meeting statement through February 2023. This phrase indicated that the Committee thought that a series of rate hikes would be needed “to return inflation to 2 percent over time.” However, the Committee softened the language in the March 22 statement—the 25 bps rate hike on March 22 occurred when financial market volatility was still elevated in the aftermath of the bank failures—to “some additional policy firming may be appropriate.” The Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) that the FOMC released after the March 22 meeting showed that 10 of the 18 Committee members thought that a target range of 5.00%-5.25% would be appropriate at the end of 2023 (Figure 3). If the FOMC does indeed hike by 25 bps on May 3, then the target range would rise to the level that just a month ago the majority of Committee members thought would be appropriate at the end of this year.

Therefore, we can envision the FOMC dropping the reference to “some additional policy firming” in the May 3 statement in a signal that the tightening cycle may be at its end. However, we would expect the statement to include that future adjustments to the fed funds target range—rather than future increases—will take into account the same factors listed in the March statement, “the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity an inflation, and economic and financial developments.” The less specific language around the direction of future changes would keep the door open to additional tightening should conditions warrant, while acknowledging the change that rates could eventually be adjusted in a downward direction. That said, we believe the Committee will stress the need to keep policy “sufficiently restrictive to return inflation to 2 percent over time.” In addition, the statement likely will continue to note that “the Committee remains highly attentive to inflation risks.”

With the policy path nearing a turning point, the possibility of some disagreement among Committee members about next steps is growing. Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee, who is a voting member of the FOMC this year, has most vociferously called for the need to be cautious, given March’s banking system events. However, a number of other Fed officials, including FOMC Vice Chair Williams and Governor Waller, have highlighted that with inflation still high and financial conditions not significantly tighter since early March, it is appropriate for the policy rate to move up more. We think the policy statement may thread the needle between these diverging views if it drops the reference to “additional policy firming” but does not fully dismiss the possibility of additional tightening. However, if the statement relays future increases as more likely than not, we would expect at least one dissent.

FOMC Likely Will Maintain Current Pace of QT

In addition to rate hikes, the FOMC has been tightening financial conditions by allowing previously purchased securities to roll off the central bank’s balance sheet. At present, the Federal Reserve allows up to $60 billion of Treasury securities and up to $35 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) to roll off the balance sheet every month. We believe the Committee will maintain this current pace of “quantitative tightening” (QT) until the economy shows unmistakable signs of entering recession and/or short-term funding markets show strains à la September 2019 when money market rates spiked. Assuming that short-term funding markets remain stable between now and the upcoming FOMC meeting, we would expect the Committee will reaffirm the current pace of QT tightening on May 3.

Rate Cuts Still Some Ways Off Into the Future

We believe that the increase in the fed funds target range that we anticipate on May 3 will most likely be the last rate hike in this tightening cycle. As noted previously, it appears that most FOMC members are comfortable with a target range of 5.00%-5.25% for the fed funds rate at the end of this year. Although this point estimate for year-end 2023 would not preclude the FOMC from taking rates above this range and then easing policy before the end of the year, our sense is that policymakers envision 5.00%-5.25% as the peak range in rates in this tightening cycle. Therefore, we believe the bar for further tightening beyond this range is high for many FOMC members.

After the May meeting, we think policymakers will pause to assess the impact of past policy tightening as well as tighter lending conditions in the wake of the recent banking system stress. The most recent Federal Reserve Beige Book signaled that banks had tightened lending standards in many parts of the country amid increased uncertainty and concerns about liquidity. If our current macroeconomic forecast, which is discussed in detail in our most recent U.S. Economic Outlook, is reasonably accurate, then we believe that the data on economic activity, the labor market and inflation that will be available at the time of the June 14 meeting will be soft enough to convince most policymakers to remain on hold at that meeting (Figure 4). Although we believe that signs of impending recession will be unmistakable by autumn, we suspect that the FOMC will refrain from cutting rates immediately because inflation likely will still be running well in excess of 2%. But we expect inflationary pressures to lessen as the downturn in economic activity gathers pace later this year. Therefore, we look for the FOMC to begin cutting rates at the end of 2023, and we forecast that the easing cycle will remain in place well into 2024.

Is a RRP Tweak Coming?

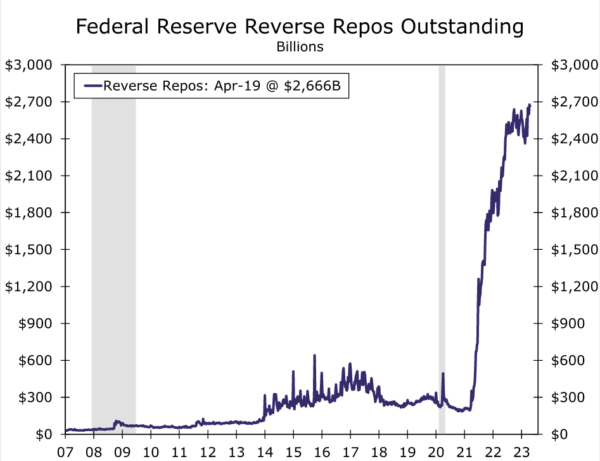

A common question we have been asked in recent months is whether the Federal Reserve would consider tweaking the terms of its overnight reverse repurchase agreement facility (RRP) at an upcoming meeting. This line of questioning has gathered steam as usage of the facility has skyrocketed and concerns have grown regarding deposit outflows from banks into money market funds (Figure 5). But first, what are reverse repurchase agreements, and why is the Federal Reserve conducting them to such scale?

In a reverse repurchase agreement conducted with the Federal Reserve, a financial institution parks its cash at the central bank on an overnight basis and earns an interest rate that is set by the Fed.1 Eligible counterparties include many banks, money market funds and government-sponsored enterprises, but money market funds comprise the overwhelming share of the daily volume. Since government money market funds invest in government securities or repurchase agreements that are collateralized by government securities, the RRP facility is a natural home for these funds’ investable cash. RRP usage has exploded over the past couple of years for several reasons: declining Treasury bill supply, debt ceiling challenges, regulatory considerations at banks and a desire to reduce interest rate risk in an environment of tremendous uncertainty about the outlook for short-term interest rates.

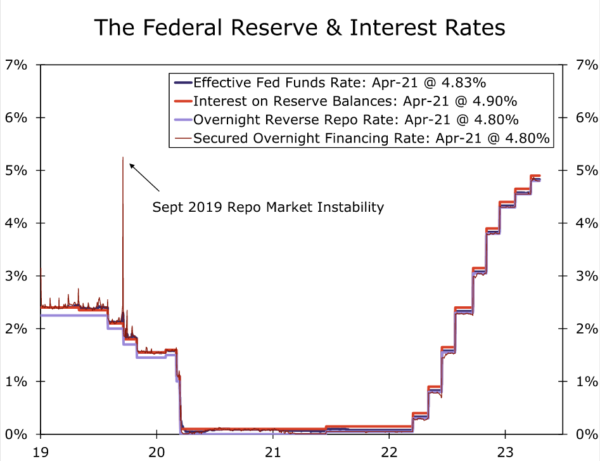

The Federal Reserve conducts RRPs in order to control short-term interest rates, such as the federal funds rate. Before 2008, the Federal Reserve would conduct open market operations to affect changes in money market rates. On any given day, the central bank would perform small purchases and sales of securities in the open market. These purchases/sales would add/drain reserves from the financial system and ensure that the federal funds rate was trading near the FOMC’s target. This in turn would flow through to other key short-term interest rates, such as LIBOR or Treasury bill yields.

However, post-2008, the size of daily open market operations needed to affect the federal funds rate were too large to be practical, and a new framework was adopted. This new system was designed to put a “floor” under short-term interest rates.2 In theory, an institution with access to the RRP facility should have no incentive to lend money on an overnight basis for less than it can earn at RRP. In this sense, RRP is similar to the interest on reserve balances (IORB) that the Federal Reserve pays to banks when those institutions put money on deposit at the central bank. Together, IORB and RRP form the foundation of the Federal Reserve’s framework for controlling the federal funds rate and, by extension, other key short-term interest rates, such as the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR).

The current RRP rate is 4.80%, while the current IORB setting is slightly higher at 4.90%. Since IORB is set above the RRP rate, banks generally opt for the former, while money market funds invest in the latter, given that they do not have access to IORB. The Federal Reserve’s use of these two administered rates has successfully pushed the federal funds rate, SOFR and many other money market rates up from near 0% as recently as March 2022 to nearly 5% today (Figure 6).

Some commentators have suggested that the FOMC could tweak the terms of the Fed’s RRPs in order to make the facility less attractive and thus reduce RRP usage. For example, the Committee could approve a cut on the rate paid on RRPs, or it could reduce the counterparty limits, which currently stand at $160 billion. The argument generally goes that funds would then flow out of RRP and back into the banking system, where it might improve banking system stability or the flow of credit. A full debate of the pros and cons of such a move are beyond the purview of this report, but we believe it is important to bear in mind one very key drawback of cutting the RRP rate or reducing counterparty limits. As we have already discussed, the rate paid on RRPs is a key anchor that keeps the federal funds rate within the FOMC’s target range. Thus, cutting the RRP rate in a material way would be a de facto rate cut, something the FOMC would very much like to avoid given its ongoing fight against high inflation.

A very small tweak is perhaps possible at some point, such as decreasing the RRP rate slightly while simultaneously increasing IORB by a commensurate amount. But it is not clear to us that this would have a material impact on RRP facility usage, if at all. For now, we suspect the FOMC is content to let the current framework operate as it has over the past year, with the hope that RRP balances will come down organically once a debt ceiling resolution is reached, T-bill supply expands, and more certainty emerges for the future path of monetary policy. If these developments occur, then money market funds may be more able and willing to allocate money away from RRP and towards T-bills and private repo. Governor Waller and other FOMC members have espoused a view along these lines, and the minutes from the most recent FOMC meeting showed few signs of any pending changes to IORB or RRP. The RRP facility may have its flaws, but for now it continues to perform its primary responsibility of keeping the fed funds rate where the FOMC wants it to be. As a result, we suspect policymakers will refrain from any technical tweaks at the May 3 FOMC meeting.