Summary

- We expect the FOMC to hold the fed funds rate steady at 4.25%-4.50% for a fifth consecutive meeting at the conclusion of its upcoming gathering on July 30. Data over the inter-meeting period suggest the labor market remains roughly at “full employment,” while inflation has edged up slightly and continues to run higher than the FOMC’s 2% target. As such, most members are likely to support policy remaining “modestly” or “moderately” restrictive at this time.

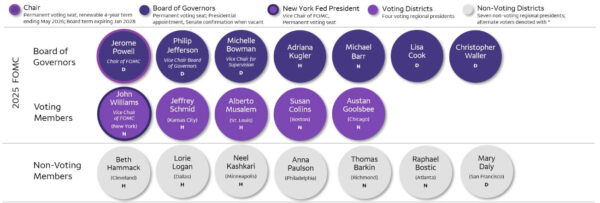

- That said, a split has emerged on the Committee about how to balance current risks to the outlook and the near-term path of rates. Some Committee members, most notably Governors Waller and Bowman, see risks to the labor market over-shadowing risks to inflation and appear supportive of a rate cut at the upcoming meeting. But, the majority of the Committee seems reluctant to resume rate cuts given the lingering upside risks to inflation generated by higher tariffs, relatively easy financial conditions and resilient economic activity.

- With the July jobs report and a number of key trade deadlines falling shortly after the July FOMC meeting concludes, we do not expect the Committee to signal easing is forthcoming at its next meeting on September 16-17. Rather, we expect to see fairly minimal changes to the post-meeting statement to help the Committee preserve optionality about future policy decisions.

- Public pressure from the Trump administration for the FOMC to lower rates and discussions of replacing Chair Powell have intensified since the Committee’s last meeting, putting the question of the central bank’s independence in the spotlight. The Federal Reserve has never been fully separate from the political process, but a combination of laws, agreements and norms permit a significant amount of independence when it comes to setting monetary policy. Will policy setting stay independent in the months ahead?

- Our expectation is that Chair Powell will serve out the remainder of his current term, which expires in May 2026. The next Chair will likely lead the central bank in a more dovish direction, but we expect changes will be gradual rather than a complete departure from recent convention. The Committee is comprised of a mix of 12 voting members from the Board of Governors and regional Federal Reserve Banks, and decisions are made by consensus. One person, even the Chair, can only change monetary policy so far and so fast.

- An overly-dovish bias of the next Fed Chair could prove counterproductive to the administration’s aims. If the FOMC were to lose its inflation-fighting credibility, less foreign demand for U.S. assets, higher inflation expectations and a steeper yield curve strike us as plausible outcomes. In our view, moderate long-term interest rates are predicated on a credible, independent Federal Reserve and well-anchored inflation expectations.

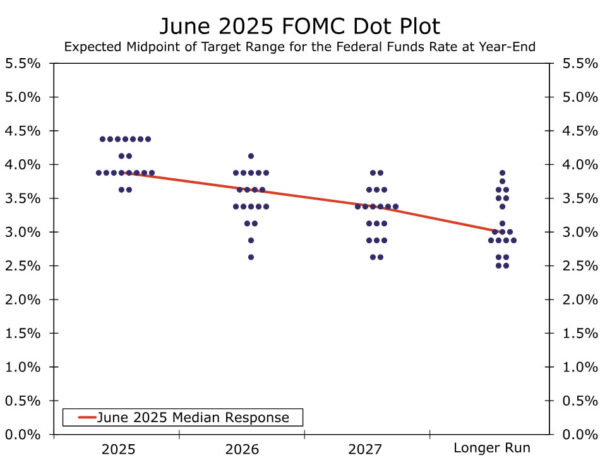

- Most Committee members already seem inclined to cut rates this year, as illustrated in the June Summary of Economic Projections and recent Fed speak. We expect the resumption of policy easing this autumn to alleviate some of the current political pressure on the Committee in the months ahead.

“I’m Not Thinking About That”

Ahead of the FOMC’s July 29-30 meeting, the race to become the next Chair and the fate of the current Chair have dominated Fed-related headlines. Yet, we expect Chair Powell and the rest of the Committee to be squarely focused on the job at hand: restoring price stability while maintaining full employment during a time of significant changes to and uncertainty around economic policy.

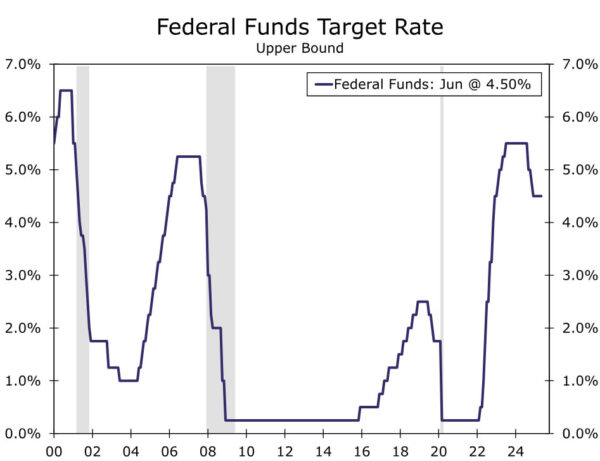

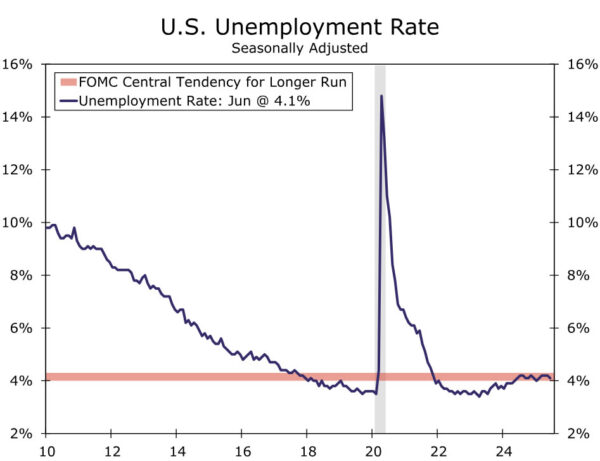

At 4.25%-4.50%, the fed funds target range has been unchanged since December (Figure 1). We expect the Committee to once again hold rates steady at the conclusion of its upcoming meeting on July 30. Members continued to view the labor market as “solid” at the June FOMC meeting, and data over the inter-meeting period give little reason to alter this characterization. Payroll growth has steadied around a 150K monthly pace since April even as gains have become more narrowly based across industries. While demand for workers continues to gradually subside, slower growth in labor supply helped to reduce the unemployment rate to 4.1% in June, putting it a tick below the Committee’s median longer-run estimate (Figure 2). In other words, the maximum employment side of the Fed’s mandate continues to be met.

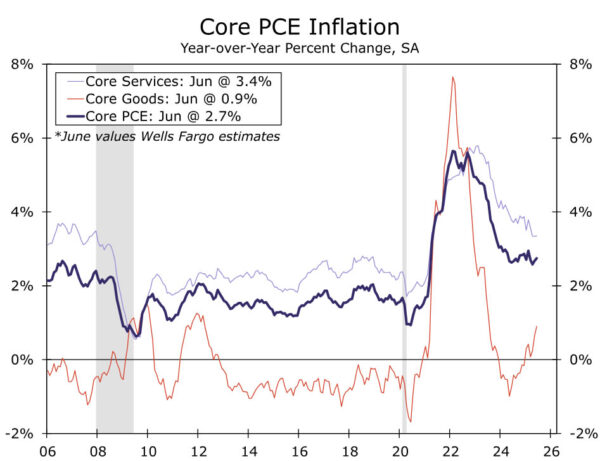

That said, inflation continues to run above the Committee’s 2% target. The Consumer Price and Producer Price indices for June point to the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the PCE deflator, picking back up to a year-over-year rate of 2.5%. For the core inflation measure, the renewed uptrend in goods inflation has been thus far largely offset by softening in services inflation (Figure 3). But, Fed officials remain on guard about the upward pressure on inflation stemming from higher tariffs. While noting the uncertainty that surrounds the timing and magnitude of the effects of tariffs on inflation, all FOMC participants in the June Summary of Economic Projections estimated PCE inflation would end the year above its current 2.3% year-over-year rate.

How Split?

While the FOMC unanimously decided to leave the fed funds range unchanged at its prior meeting in June, a split in the Committee has emerged about the path of rates going forward. In the June Summary of Economic Projections, seven participants saw no cuts as likely to be appropriate this year, while eight aligned with the median of two 25 bps cuts (Figure 4). A couple of participants saw the prospect for three cuts this year. Governors Bowman and Waller made headlines shortly after the June meeting by opening the door to a rate cut as soon as the July meeting. In a speech late last week, Governor Waller pointedly said, “I believe it makes sense to cut the FOMC’s policy rate by 25 basis points” at the upcoming meeting.

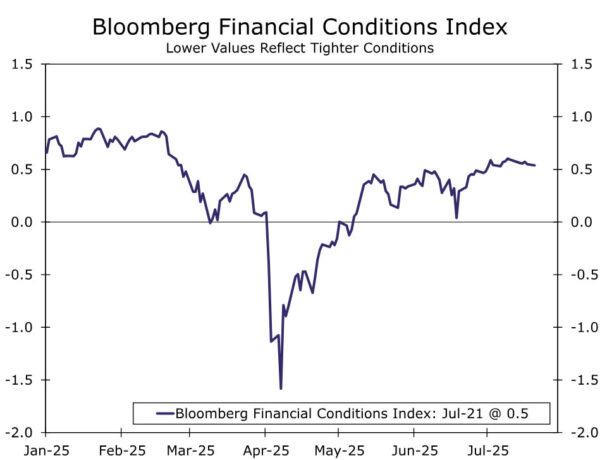

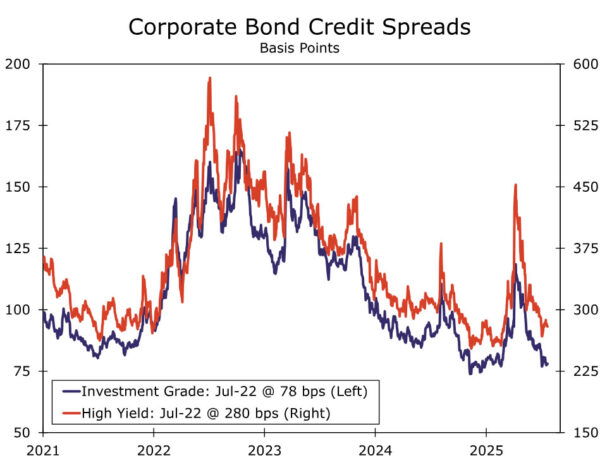

However, the vast majority of the Committee is not as ready to begin resuming rate cuts. The June meeting minutes and recent Fed speak show more Committee members view the upside risks to inflation as being greater than the downside risks to employment at this juncture. After the 2021-2022 spike in inflation proved more severe and longer-lasting than Fed officials first assumed, many are mindful of the risk that tariff-induced inflation may prove more persistent and long-lasting. Moreover, with most officials viewing policy as only “moderately” or “modestly” restrictive, expectations persist for activity to remain resilient in the near term. The view that policy is not overly restrictive is backed by the behavior of financial conditions, which have eased considerably in recent months (Figure 5). U.S. equity markets are once again at all-time highs, while credit spreads are back near multi-year tights (Figure 6). Shortly before the blackout period, FOMC Vice Chair & New York Fed President John Williams, who we view as a centrist on the Committee, stated that the current restrictiveness of policy is “entirely appropriate” amid his expectations for tariffs to generate a lift to inflation in the coming months.

As such, we do not expect any hints in the post-meeting statement or press conference that a resumption of policy easing is around the corner. The outlook for trade policy remains highly uncertain and makes forward guidance challenging. Only days after the July FOMC meeting concludes are deadlines for settling “reciprocal” tariffs (Aug. 1 for most nations; Aug. 12 for China) and the start of the court case to determine whether the “reciprocal” tariffs are legal under the International Emergency Powers Act (July 31). Officials also will receive two more months of inflation and labor market data before their next meeting on September 17. We suspect that will be enough to keep most participants comfortable in wait-and-see mode somewhat longer.

Governor Waller seems all but assured to dissent and may be joined by Governor Bowman, but the bulk of the Committee looks poised to keep their options open for the future path of rates. Note that two governors (i.e., not regional Fed presidents) dissenting is unusual: it last occurred in December 1993. Multiple governors dissenting would be another sign of the current split within the Committee regarding the appropriate path of monetary policy.

The post-meeting statement could include a slight downgrade to the characterization of recent activity (e.g., from a “solid” to “moderate” pace”) following a slower pace of consumer spending reported since the June FOMC meeting, but the prior characterization of the labor market as “solid” and inflation as “somewhat elevated” still holds, in our view. The only other change we expect to see is around uncertainty about the outlook no longer described as “having diminished.”

Federal Reserve Independence: A Refresher

With most FOMC members signaling that the inflation and labor market backdrop warrants keeping rates steady somewhat longer, pressure from the Trump administration to lower the fed funds rate has intensified. This has put the topic of monetary policy independence front and center.

As an institution, the Federal Reserve’s independence has evolved over time, but it has never been fully separate from the political process. The president appoints the governors to the Federal Reserve Board, including the Chair, and the Senate votes to confirm these individuals. Congress sets the Federal Reserve’s goals and mandates through law. The Federal Reserve was established by an act of Congress, and subsequent Congresses have changed the Federal Reserve’s structure and objectives. The Fed’s dual mandate for full employment and price stability, for example, was established by Congress in 1977.

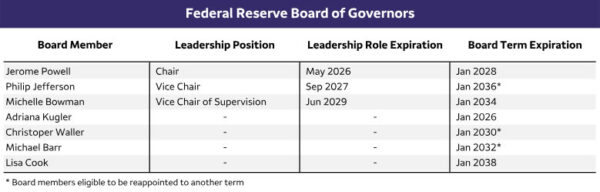

That said, a combination of laws, agreements and norms permit the Federal Reserve a significant amount of independence when it comes to setting monetary policy. The 12 regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents are not appointed by the president but instead are selected by their boards, with the latter typically made up of individuals working in business, finance and other local community leaders. Governors receive 14-year terms, and the seven governors’ terms are staggered every two years, helping to ensure the Board has appointees from multiple presidents (Figure 7). In addition, the Federal Reserve is self-funded and does not receive explicit appropriations from Congress.

During World War II, the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve explicitly cooperated, with the central bank agreeing to buy U.S. Treasury securities in enormous quantities to help finance the war effort. After the war, an agreement between the Treasury and Fed was eventually reached, known as the Treasury-Fed accord. This accord helped establish the Federal Reserve that we know today: one where monetary policy decisions are made in response to economic conditions such as unemployment and inflation, rather than fiscal needs.

What Does the Pressure Mean for the Path of the Fed Funds Rate?

A full review of the many twists and turns in the Fed’s tug of war over its independence is beyond the purview of this note. More directly, the question we have gotten most often from clients lately has boiled down to more or less the following: will the next Fed Chair dramatically alter the course of monetary policy, i.e., will policy setting still be independent? Although it is still somewhat premature to say given that we do not know who the selection will be, our sense is that the next Chair will lead the central bank in a more dovish direction. Yet, we expect changes will be gradual and still within the general consensus of economists and financial markets, rather than a complete departure from recent convention.

The Chair is the most important member of the FOMC, but it is still a Committee that requires consensus to act. If a new Chair came to the FOMC and attempted to alter course in a dramatic way, we suspect there would be push-back from much of the rest of the Committee, limiting the policy change. Assuming Chair Powell and Vice Chair Jefferson resign from the Board when their leadership positions expire in May 2026 and September 2027, respectively, President Trump will have three open seats to fill over his four-year term, conditional on no other unexpected vacancies (Figure 8). But, that still leaves four other governors as well as the 12 regional Fed presidents in a position to continue to influence monetary policy via their seats at the table.

If a new Chair came to the FOMC and attempted to alter course in a dramatic way, we suspect there would be push-back from much of the rest of the Committee, limiting the policy change.

Furthermore, the current Committee already seems inclined to cut rates over the next year or two. As discussed earlier, the dot plot from June had a median projection of 50 bps of easing this year and 100 bps of cumulative easing through 2027. We think the political pressure for the FOMC to cut rates will be reduced if Fed leaders cut rates by 50-100 bps at some point over the next few quarters, as is our current base case forecast. We also think the pressure to cut rates will ease somewhat if a more clear acceleration in consumer prices takes hold.

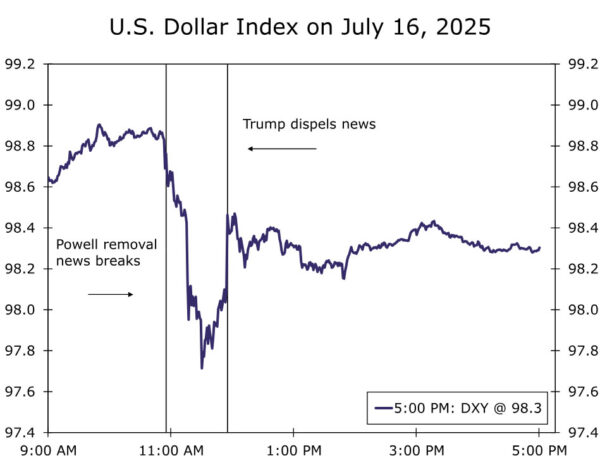

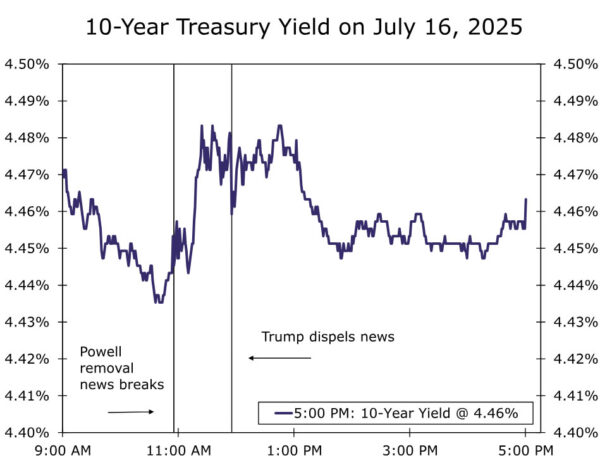

Finally, if the FOMC were to adopt an overly-aggressive dovish bias, it is not immediately clear to us that it would produce the financial market outcomes desired by the Trump administration. On July 16, breaking news headlines seemed to suggest that President Trump was actively considering removing Chair Powell from his position. About an hour later, the president dispelled this report, but the initial reaction in financial markets was lower equity prices, a weaker dollar and higher long-term interest rates (Figures 9, 10). Admittedly, this was a short-lived event and is only one episode of data. But, if the FOMC were to lose its inflation-fighting credibility, less foreign demand for U.S. assets, higher inflation expectations and a steeper yield curve strike us as plausible outcomes. In our view, moderate long-term interest rates are predicated on a credible, independent Federal Reserve and well-anchored inflation expectations.

Thus, for the time being, we are not inclined to make any major forecast changes to our outlook for the federal funds rate in light of the incoming change in Fed leadership. It remains to be seen who the president will select and who the Senate will confirm, and one person, even the Chair, can only change monetary policy so far and so fast. Furthermore, our expectation that the FOMC will cut the fed funds rate by 75 bps by year-end should help alleviate some of the pressure on the Committee. That said, this is clearly a major risk to the financial market and economic outlook as 2026 comes closer into view. As the President’s thinking on the candidates evolves, we will have more to say on the subject in future reports.