Summary

- We expect the FOMC to reduce the fed funds rate by another 25 bps to 3.50%-3.75% at its December 10 meeting. The FOMC will not have the October and November Employment Situation and CPI reports as initially planned, but the latest available data suggest continued softening in labor market conditions and receding inflationary pressures outside of tariffs.

- The FOMC has grown increasingly split over its near-term course of action. Generally speaking, the Board of Governors has a dovish skew, while the regional Fed presidents—who do not all vote—lean more hawkish. Multiple dissents seem likely. While we expect opposition in both directions of the policy decision again, more dissents are likely to be in favor of keeping the policy rate unchanged.

- A more hawkish post-meeting statement could be used to limit the total number of dissents. We expect the statement to signal a higher bar to additional rate cuts and to hint that a hold in January is most Committee members’ working assumption.

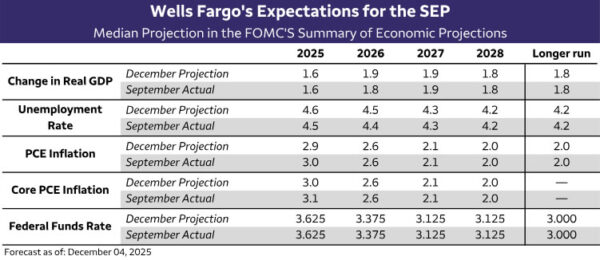

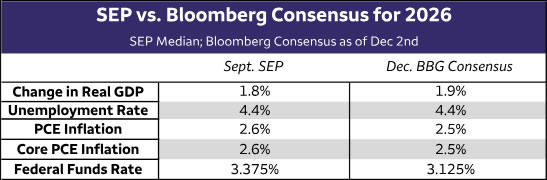

- To the extent that adjustments are coming to the Summary of Economic Projections, we suspect changes to 2025 economic forecasts will be in the direction of higher unemployment and lower inflation—consistent with another 25 bps rate cut at this meeting (see Table). Looking ahead to 2026, major changes seem unlikely. If the medians are to move, we think they are more likely to drift up a tenth or so for GDP growth and the unemployment rate, while edging down a tick for inflation.

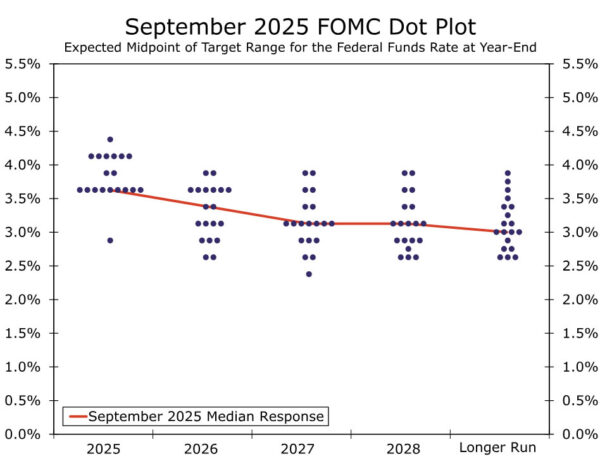

- Our expectation is that the median dot for 2026 will remain unchanged at 3.375%. That said, it would take just one participant at the current median of 3.375% moving their dot lower for the median to fall. Given the potential for a slightly higher unemployment rate and slightly lower inflation in the 2026 projections, we see the risks to the 2026 median dot as skewed to the downside.

- With quantitative tightening (QT) having ended on December 1, attention has turned to when reserve management purchases will begin to preserve the Fed’s ample reserve framework. We do not expect a decision at this meeting, and instead look for the start of reserve management purchases to be announced at the March 18 meeting.

Jobs Market Softness Enough to Keep FOMC on Course for Another Cut

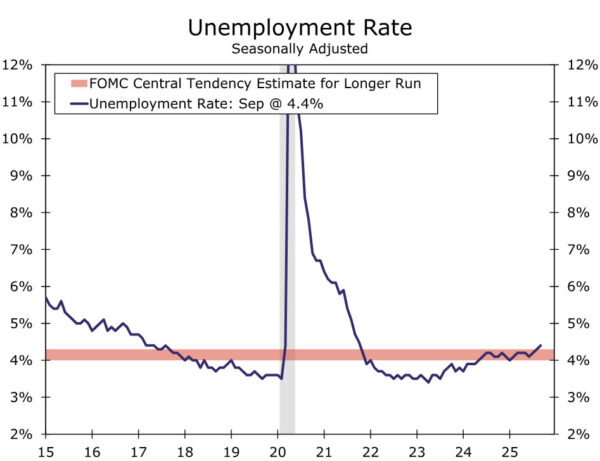

We expect the FOMC to proceed with returning policy toward a more neutral stance and reduce the fed funds rate by another 25 bps to 3.50%-3.75% at its upcoming meeting on December 9-10. Although the FOMC will not have the October and November jobs report at this meeting as initially planned, the latest available labor market data suggest that conditions have continued to slowly soften. While nonfarm payroll growth firmed in September, the unemployment rate rose to 4.44%, placing it above the Committee’s central tendency range for “maximum employment.” (Figure 1).

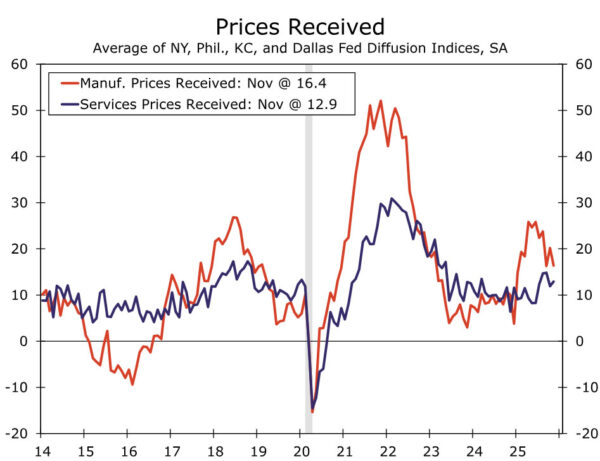

Fresh data on inflation since the FOMC last met have been more limited. The Committee will receive the September PCE price index prior to its upcoming meeting. The PPI and CPI data for that month point to the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation rising 2.8% in the 12 months through September on both a headline and core basis, largely unchanged from the readings seen over the summer. While still frustratingly above target, there are few signs of inflationary pressures bubbling up further, in our view. Average hourly earnings growth is generally consistent with 2% inflation, while the September PPI showed the pickup in inflation this year remains limited to the goods sector. Inflation expectations generally remain well-anchored, and businesses also appear to be raising prices a bit more slowly over the past month or so. Fewer firms in the NFIB survey have been reporting higher prices, while the latest regional Fed PMIs show prices received moderating (Figure 2).

A Fed Divided

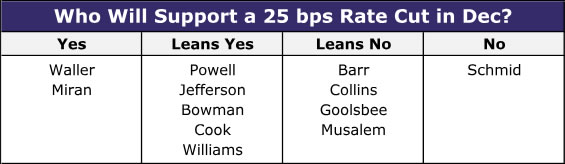

With inflation continuing to run above target and the FOMC having already cut 50 bps since the summer, the Committee has grown increasingly split on its next course of action. The public comments from FOMC officials in recent weeks reflect this unusually deep divide. Governors Miran and Waller have explicitly stated their support for rate cuts at the December meeting. Governors Jefferson, Bowman and Cook have not been quite as explicit in their support, but their public remarks in recent months lead us to believe they also will support another 25 bps rate cut in December. If there is a hawk lurking on the Board, it is probably Governor Barr. Governor Barr expressed some concern that “we’re seeing inflation still at around 3% and our target is 2%” in comments on November 20.

In contrast, the voting regional Fed presidents have sounded more hawkish. Kansas City Fed President Jeffrey Schmid dissented against cutting rates in October and seems likely to do so again in December. Boston Fed President Susan Collins recently expressed no “urgency” for more accommodative monetary policy, while St. Louis Fed President Alberto Musalem said there was “limited room for further easing without monetary policy becoming overly accommodative.” Even the oft-dovish Chicago Fed President Austan Goolsbee has sounded more skeptical of additional rate cuts in his recent public remarks. Yet, there was one key exception to the hawkish tilt of regional Fed presidents recently. New York Fed President John Williams stated on November 21 that he sees room for another rate adjustment “in the near term,” a key signal that this leader on the FOMC seems likely to support a December cut. Conspicuously quiet in recent weeks has been Chair Powell, who has not made any public comments on monetary policy since the last FOMC meeting on October 29-30.

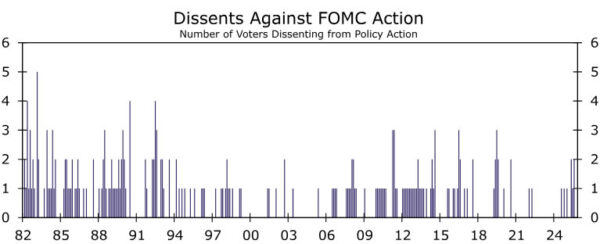

We believe that, on net, there will be a critical mass of support for a 25 bps rate cut in December, particularly among the FOMC’s leadership (Figure 3). That said, there is clearly disagreement within the ranks. Should the Committee cut rates like we expect, we can easily envision three or four votes against the action, with dissents once again possible in both directions of the policy decision. Governor Miran in particular could dissent in favor of a 50 bps cut if his vote is not needed to lock in 25 bps. The last time there were three dissents was September 2019, while four dissents last occurred in October 1992 (Figure 4).

The Statement Will Be Used to Limit Hawkish Dissents

We believe the ultimate number of dissents will depend on the guidance the Committee provides about future policy adjustments in its post-meeting statement. To help appease voters who are reluctant to cut again at this particular meeting, we expect the statement to signal a higher bar of additional rate cuts. This could be done by saying, “In considering the timing and extent of any additional adjustments to the target range for the federal funds rate…”, with the italicized portion an insertion to the current statement text. Additional emphasis on returning inflation to the FOMC’s 2% target could also help muster support from some hawks frustrated by inflation’s lengthy overshoot of target.

In the opening paragraph on recent economic conditions, we expect the statement to be unchanged except in reference to the labor market. We could see the sentence on the jobs market truncated to merely state that “Job gains have slowed this year, and the unemployment rate has edged up but remains low.” The acknowledgment of the labor market’s ongoing cooling would be consistent with the Committee moving forward with another cut at this meeting.

SEP: No Change to the Median Dots

The upcoming FOMC meetings will include an update to the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP). The median projections in the current SEP, last updated in September, still look about right for 2025, in our view. A 4.5% unemployment rate for 2025 is in line with our most recent forecast from November 19, although September’s upside surprise of 4.4% opens the door to the median edging up to 4.6%. The median SEP projections for headline and core PCE inflation of 3.0% and 3.1%, respectively, are modestly above our latest projections of 2.8% and 3.0%, respectively, but they are not dramatically out of line either. Although the government shutdown has clouded the outlook, the economic data appear to have been moving in line with the median participant’s 2025 projections from back in September.

Looking ahead to 2026, we do not see much reason for the economic projections to change materially. The median projections from September are broadly in line with the latest Bloomberg consensus forecasts for 2026 (Figure 5). If the medians are to move, we think they are more likely to drift up a tenth or so for GDP growth and the unemployment rate, while edging down a tick for inflation. (Table).

More notably, the median Committee participant projects 25 bps less easing than the Bloomberg consensus and our own forecast for 2026 (Figures 5 and 6). Our expectation is that the median dot for 2026 will remain unchanged at 3.375% in a sign that most participants on the Committee have not materially changed their minds about the appropriate stance of monetary policy next year. An unchanged median dot in 2026 also would be another nod to the simmering hawkish sentiment among some participants on the Committee. That said, it would take just one participant at the current median of 3.375% moving their dot lower for the median to fall. Given the potential for a slightly higher unemployment rate and slightly lower inflation in the 2026 projections, we see the risks to the 2026 median dot as skewed to the downside.

We expect the median dots beyond 2026 to remain unchanged as well. The dots for 2027 and 2028 are more clustered around the median and, being so close to neutral, seem less likely to move. The longer run median seems primed to rise by 12.5 bps or 25 bps at some point given the skew, but we have no reason or cause to believe it will occur at this meeting.

Likely No Changes to Balance Sheet Policy in December

At its previous meeting, the FOMC announced the end of quantitative tightening (QT) effective December 1. The end of QT has sparked a debate about when the Federal Reserve will begin growing its balance sheet again in the form of reserve management purchases. Reserve management purchases are a staple tool of the ample reserve framework used by the Federal Reserve to maintain interest rate control and ensure the smooth functioning of financial markets. It is important to understand that reserve management purchases are distinct from quantitative easing (QE) asset purchases meant to stimulate the economy. The latter involve the central bank buying longer-dated Treasury securities and mortgage-backed securities, putting downward pressure on longer-term interest rates and mortgage spreads and thus easing financial conditions. These purchases also often have a signaling effect as markets anticipate that rate hikes remain a long way off while QE is happening.

In contrast, reserve management purchases involve swapping one riskless asset (bank reserves) for another essentially riskless asset (Treasury bills) to ensure bank reserves remain ample. Federal Reserve officials have been very clear (see here and here as examples) that these purchases would be the next phase of reserve management policy and in no way represent a change in the stance of monetary policy. We agree with this assessment, and the beginning of reserve management purchases will have no bearing on our view of the stance of monetary policy.

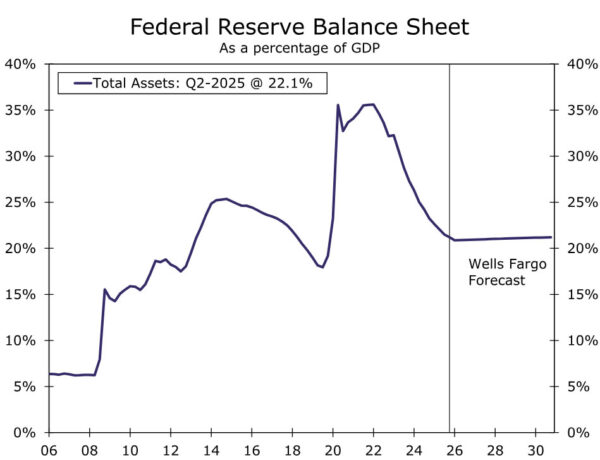

Our expectation is that the FOMC will announce the start of reserve management purchases at the March meeting, with purchases beginning April 1. If realized, the Fed’s balance sheet would start to grow again in nominal terms, although it would be roughly unchanged as a share of GDP (Figure 8). We estimate that these purchases will total approximately $25 billion per month and be comprised entirely Treasury bills. The FOMC may not immediately begin with purchases of this size and instead might phase them in similar to how QT was tapered down.

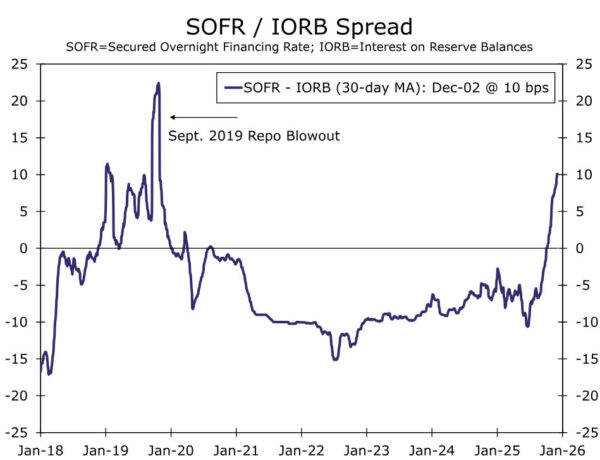

We think the risks are skewed toward an earlier start date for reserve management purchases, e.g., announced at the January meeting for a February start. We will be watching money market conditions closely into year-end as we fine tune our forecast. Repo rates have risen sharply relative to the interest rate the Fed pays banks on its reserves, a sign that funding conditions have tightened notably (Figure 9). If year-end goes relatively smoothly, we likely will be inclined to stick with this timing, whereas if it is a sloppy year-end, we would be inclined to pull-forward our forecast for the start of reserve management purchases.