Summary

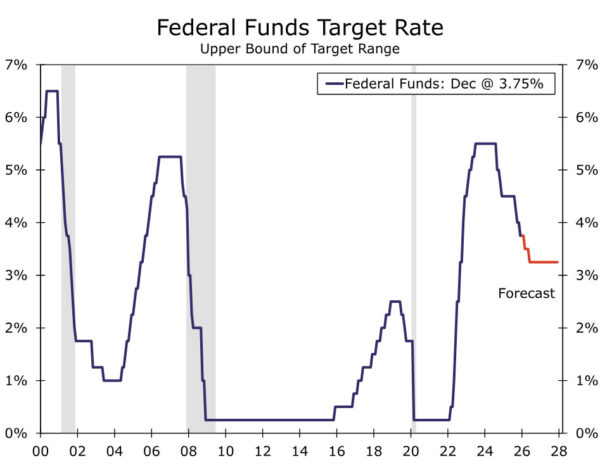

- As expected, the FOMC reduced the fed funds target range by 25 bps to 3.50%-3.75% and signaled that additional easing will face a higher bar at its next meeting on January 28.

- The post meeting statement signaled this higher bar to future cuts by noting it was now considering the “extent and timing” of additional adjustments. The suggestion that the FOMC would not be so ready to cut the policy rate again in the near term likely helped to limit the number of hawkish dissents to two (Presidents Goolsbee and Schmid). Governor Miran again dissented in favor of a 50 bps cut.

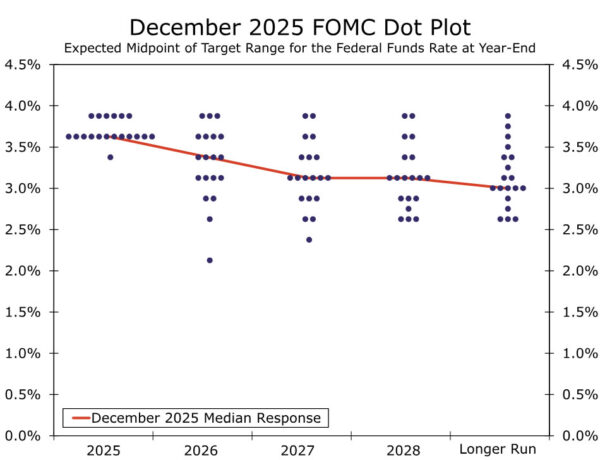

- Despite two hawkish dissents and the dot plot revealing four other regional bank presidents preferred to hold the policy rate steady today, the Committee maintains an easing bias. The updated Summary of Economic Projections showed the median estimate for the policy rate at the end of next year to be 3.375%, unchanged from September.

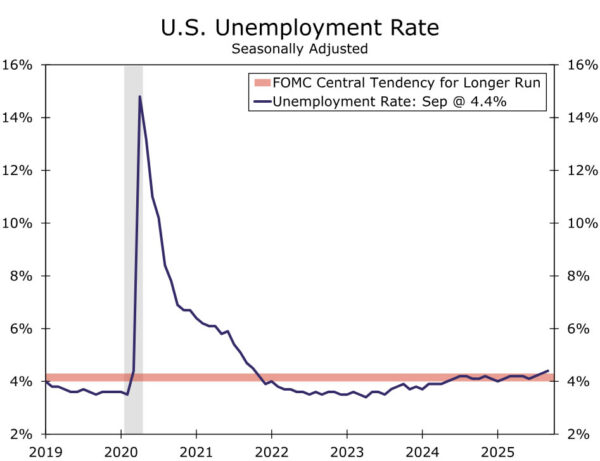

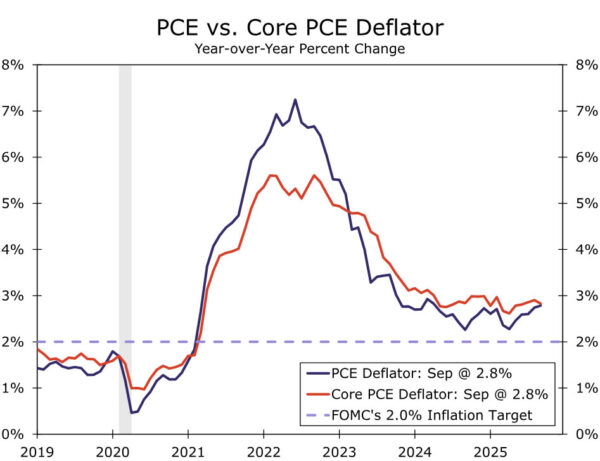

- The expectation among most members to ease next year reflects projections for the unemployment rate to be a touch above most participants’ estimate for full employment next year, while inflation resumes its progress back toward—albeit not all the way to—the FOMC’s 2% target. The Q4-2026 median projection for the unemployment rate was unchanged at 4.4%, while the median estimate for headline and core PCE inflation ticked down to 2.4% and 2.5%, respectively. More noticeable was the median estimate for GDP growth next year rising half a percentage point to 2.3% on a Q4/Q4 basis, putting it closer to our above-consensus estimate of 2.5%.

- There is a slew of economic data between now and the next meeting on January 28, and we will be monitoring it closely and adjusting our forecast as conditions warrant. Our base case remains that the current easing cycle is not over yet but rather that it is entering a slower phase. We continue to look for two more 25 bps cuts from the FOMC next year at the March and June meetings.

- The Federal Reserve also announced the beginning of reserve management purchases (RMPs) in an effort to maintain short-term interest rate control, keep bank reserves ample and ensure the smooth functioning of financial markets. Fed officials have been clear for months that this step in no way represents a change in the stance of monetary policy. We agree with this assessment, and the beginning of RMPs will have no bearing on our view of the stance of monetary policy.

A Cut to Close out the Year

As expected, the FOMC reduced the fed funds target range by 25 bps to 3.50%-3.75% at the conclusion of its December meeting. As was also anticipated, the decision was not unanimous. Three voting members did not support the policy decision, with dissents registered in both a more hawkish and dovish direction. Specifically, Governor Miran dissented in favor of a steeper, 50 bps cut, while Presidents Schmid (Kansas City) and Goolsbee (Chicago) dissented in favor in keeping the policy rate unchanged.

The dispersed views on the best course of action reflect the tricky environment the FOMC finds itself in. The FOMC did not have several key readings on the economy as originally scheduled due to the government shutdown (e.g., Q3 GDP, Oct. & Nov. Employment Situation and CPI, etc.). But, the latest data available continue to indicate some tension in the Committee’s employment and inflation mandates (Figures 1 & 2).

With 75 bps of cuts since September and policy not as clearly restrictive, the bar for additional easing has been raised. In the post meeting statement, the Committee gave itself more optionality around future cuts, saying that “In considering the extent and timing of additional adjustments to the target range…”, with the emphasized text new to the statement. The suggestion that the FOMC will not be so ready to cut rates again in the near term likely helped to limit the number of hawkish dissents.

The Summary of Economic Projections did signal some broader unease among the Committee besides the two hawkish dissents. The dot plot revealed that six participants in total did not favor reducing the policy rate at today’s meeting, implying four non-voting regional presidents also preferred to hold the policy rate steady. Nonetheless, a bias toward further easing persists among the Committee. The median dot for year-end 2026 and 2027 remained at 3.375% and 3.125%, respectively. The longer-run median was unchanged at 3.00%, with the dot plot illustrating that all but two participants see the current policy rate at least somewhat restrictive.

The biggest change to the SEP was a major upward revision to the 2026 growth outlook, with the median projection rising from 1.8% to 2.3%. Some of this change likely reflects the government shutdown, with Q4-2025 real GDP growth expected to see a material drag, setting the economy up for a bounce-back in Q4-2026. That said, this dynamic cannot fully explain the change, and it puts the median FOMC participant closer to our above-consensus forecast of 2.5% real GDP growth next year. Elsewhere, the changes generally were smaller, with some modest downward revisions to the inflation forecasts next year, and no change to the median longer run projections for the real GDP growth and the unemployment rate.

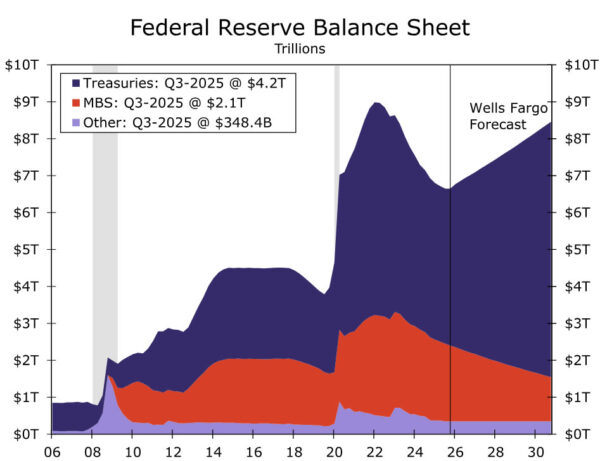

The Federal Reserve also announced that it will begin growing its balance sheet again in the coming days through the purchase of Treasury bills. As we have discussed previously, these purchases are meant to maintain short-term interest rate control, keep bank reserves ample and ensure the smooth functioning of financial markets. Fed officials have been clear for months that this step in no way represents a change in the stance of monetary policy. We agree with this assessment, and the beginning of reserve management purchases (RMPs) will have no bearing on our view of the stance of monetary policy.

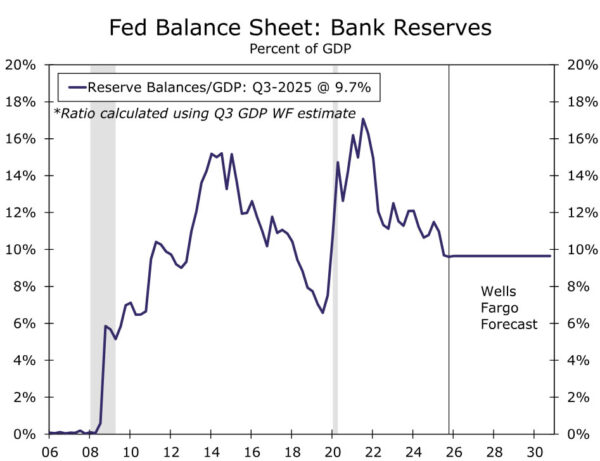

Specifically, the central bank announced that RMPs will begin on December 12 with an initial pace of $40 billion for the month. The post-meeting guidance stated that “the pace of RMPs will remain elevated for a few months to offset expected large increases in non-reserve liabilities in April. After that, the pace of total purchases will likely be significantly reduced in line with expected seasonal patterns in Federal Reserve liabilities.” Our working assumption has been that the medium term, “equilibrium” pace of RMPs will be $25 billion per month to keep bank reserves ample. We read the above guidance as indicating that RMPs will downshift to roughly this pace starting in the spring. If realized, the Fed’s balance sheet will grow by roughly $370 billion in 2026, and the reserve-to-GDP ratio will be 9.7% at the end of next year, comfortably above the lows in September 2019 when repo markets blew up (Figure 6).

Our base case remains that the current easing cycle is not over yet but rather that it is entering a slower phase. While the labor market is far from collapsing, the softening in conditions to the wrong side of “maximum employment” supports policy returning to a more neutral position. Directional progress on inflation next year should resume as the initial lift from tariffs fade, which would reduce the tension between the FOMC’s employment and inflation mandate. We continue to look for two 25 bps rate cuts next year at the March and June meetings. Next week’s economic data, specifically the “one and a half” employment report on Tuesday and the November CPI on Thursday, will be key to the outlook. We will have reports out previewing these data releases in the coming days.