Summary

- As expected, the Supreme Court struck down the president’s authority to levy tariffs under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA). President Trump was quick to announce new tariffs. The bottom line is these actions did not deliver complete relief to affected importers, but it did ease their burden even if refunds will take awhile.

- The ruling invalidates the legal basis for IEEPA tariffs, but it does not trigger automatic refunds. Importers must pursue refunds individually through established claims processes.

- Potential refunds are large, but unlikely to be fully realized. Roughly $264B in tariff revenue was collected last year, and we estimate about half—around $130B—was collected under IEEPA. The true total may be somewhat higher once January–February collections are included, but refunds will be handled case by case, meaning not all IEEPA tariff revenue is likely to be returned.

- Any refunds will arrive gradually. Payments are expected to trickle in over months, if not years, and should be delivered directly to the importers who originally paid the tariffs.

- The administration retains the ability to re‑impose tariffs, but nothing grants the President the same broad power with immediate effect as IEEPA would have.

- President Trump announced a 10% global tariff under Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974 “effective immediately”. He also announced starting Section 301 investigations.

- Section 122, Trade Act of 1974: President can impose tariffs up to 15% for 150 days to address balance-of-payments issues. Tariffs can be extended indefinitely with Congressional approval. No federal investigation required.

- Section 301, Trade Act of 1974: U.S. Trade Representative can impose tariffs for four years, under the President’s direction, if it finds unjustifiable, unreasonable or discriminatory action against U.S. businesses and/or a violation of trade agreements. Tariffs may be imposed indefinitely, if continuation is requested and extended every four years.

- This action keeps the 10% baseline global tariff effectively active, but lowers the higher IEEPA tariff burden for countries exposed to ‘reciprocal’ tariffs under IEEPA. These actions result in a lower total tariff burden. We estimate the average U.S. effective tariff rate is now around 13% in the wake of today’s actions, rather than the ~16% based on policy as of yesterday.

- Tariffs weighed on U.S. goods imports last year as firms were cautious about committing to foreign sourcing amid unsettled and frequently changing tariff policy. Some shifts in trade flows signal some rejiggering of sourcing, though permanent effects may be overstated thus far.

The Court Ruling is Something Short of a Complete Policy Reset

The Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the administration’s broad‑based tariffs imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) marks a meaningful legal turning point, but not a clean policy reset. The ruling invalidates reciprocal and fentanyl‑related tariffs enacted under IEEPA, opens the door for importers to seek refunds potentially totaling around $130 billion, and sharply curtails the president’s authority to impose sweeping tariffs without involvement.

What the decision does not do is remove tariffs from the trade policy landscape. Alternative statutory paths remain available to the administration, while none confer the same breadth or immediacy as IEEPA. In fact, President Trump announced today that all existing Section 232 and 301 tariffs remain in effect, and a 10% global tariff takes effect immediately under Section 122. He also announced the start of Section 301 investigations.

Navigating the Detour: Trade Flows in a Still-Tariffed World

The experience of U.S. importers over the past year makes clear that tariffs constrained trade less by raising costs outright than by injecting persistent uncertainty into sourcing decisions.

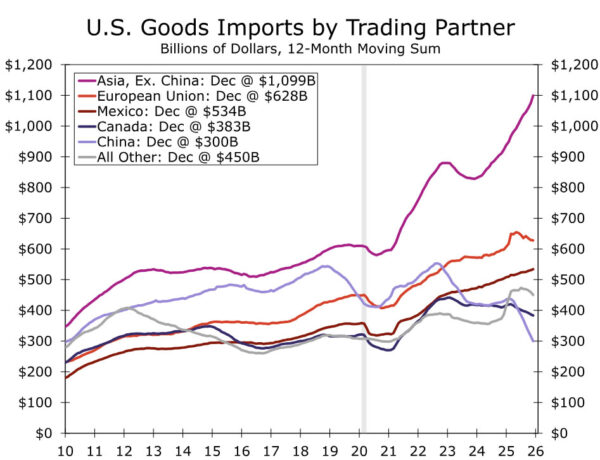

The U.S. collected nearly $265 billion in tariff revenue last year, more than three times the amount collected in 2024. Measured against total imports that means the realized average effective tariff rate rose to roughly 8% last year, up from just under 3% the year prior. With a full year of data now available, the key question is how this dramatic increase in tariffs ultimately affected U.S. import behavior.

At first glance, the answer appears counterintuitive. Total goods imports increased last year, rising 4.3% above 2024 levels. But, that top line figure obscures important underlying weakness. Once gold‑related categories are excluded, the annual gain in goods imports is cut roughly in half, suggesting the headline strength overstates the true momentum in import growth.

A closer look reveals that import growth was highly concentrated in a narrow set of categories, particularly high‑tech goods. Imports of computers, computer accessories, communications equipment, and semiconductors surged 35% over the year, consistent with other indicators showing businesses prioritizing investment in all things tech being viewed as critical to future competitiveness. While these categories were not the only contributors to import growth, they were decisive. Excluding them entirely, goods imports fell 3.6% last year (Figure 1). The lag in underlying imports suggests firms were cautious about committing to foreign sourcing amid unsettled and frequently changing tariff policy.

Supply Chains in Motion: Structural Shift or Tactical Workaround?

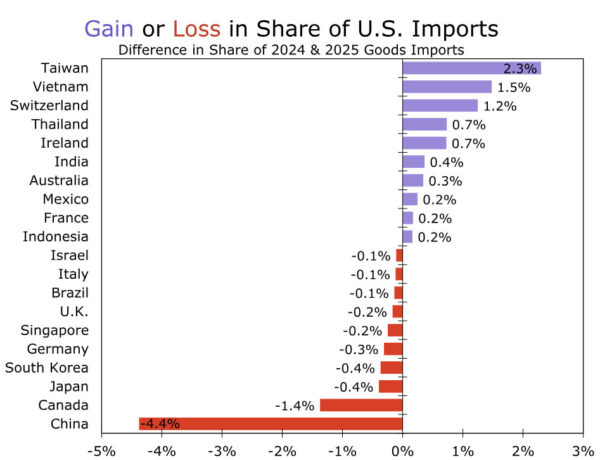

Tariffs also coincided with notable shifts in the geographic composition of U.S. imports. As shown in Figure 2, imports from China declined sharply, while shipments from other Asian economies increased. Figure 3 highlights the countries that gained—and lost—share of U.S. imports over the year. In particular, Taiwan, Vietnam and Thailand more than offset the decline in imports from China, at least in aggregate terms.

Whether this pattern reflects a genuine reorientation of global supply chains or merely a rerouting of trade flows is difficult to determine with certainty; it could well be a little of both. Source country does not necessarily imply source product either, and there is precedent for firms adjusting final assembly locations to mitigate tariff exposure. Following the first U.S.–China trade war in 2017–2019, for example, Chinese firms established or expanded production facilities in Southeast Asia, blurring the distinction between diversification and transshipment. The current data likely reflect some combination of both dynamics.

Not all country‑level shifts appear structural. Some look temporary and category‑specific. Imports from Switzerland, for instance, were driven largely by a surge in gold‑related inflows, while imports from Ireland were boosted by pharmaceutical products—a category in which Ireland accounts for roughly 40% of total U.S. imports. In both cases, demand appears to have been at least partially pulled forward ahead of potential tariff changes, and both series are historically volatile.

Cautious Adjustment, Not a Clean Break

Taken together, the data suggest that businesses are indeed reassessing supply chains in response to historically high tariffs—but the adjustment process remains incomplete. Rather than a wholesale retreat from global sourcing, the pattern so far is one of caution, selectivity and timing shifts. We repeatedly hear this anecdotally in our discussions with banking clients that source materials from overseas. Firms are willing to import when the strategic value is high, but understandably reluctant to expand exposure broadly amid policy uncertainty.

With underlying imports suppressed by hesitation rather than capacity constraints, goods imports may be ripe for a rebound in coming months, even despite tariffs. Lean inventories require replenishment whether or not uncertainty persists. Headline import growth is likely to remain a poor guide to the true state of trade, masking weakness beneath a narrow set of resilient—and strategically important—categories. The Supreme Court ruling doesn’t reset trade policy, and President Trump’s swift actions signal tariffs are here to stay even if they are adjusted in coming months.