The RBA’s focus is now, rightly, on preserving recent success by ensuring at-target inflation is sustained and the gains in the labour market are retained. However, this may prove difficult.

- The huge expansion in Australia’s public demand has supported the labour market more than it has added to inflation, allowing the RBA to focus on taming inflation without having to look over its shoulder at a deteriorating labour market.

- The non-market sector (healthcare, education and public administration) has accounted for 95% of the growth in hours worked in the economy over the past two-years. If non-market job creation over this period had instead run at its pre-pandemic pace, the unemployment rate could be up to 1 percentage point higher today.

- However, public demand is forecast to slow and there is a risk the labour market underperforms as a slowdown in non-market job creation packs a bigger punch. Importantly, the slowing in public demand is unlikely to translate into further downward pressure on inflation dynamics, at least not straight away.

- This could materially worsen the short-run trade-off between the RBA’s inflation and full-employment objectives. Instead of a world where the RBA has headroom to attend to one side of its mandate, it could be faced with a scenario where they increasingly clash.

- Meanwhile, the expansion in public demand has altered the economy’s relative sensitivity to fiscal and monetary policy in favour of fiscal policy decisions, leaving the aggregate economy less sensitive to monetary policy.

- The RBA may find itself navigating a more challenging trade-off between its objectives with a less-effective policy tool. This will see the RBA retain policy flexibility and keep policy guidance to a minimum. Given this, expect less consensus in short-term meeting outcomes and a less predictable RBA – as was on display earlier this month.

In the words of RBA Governor Michele Bullock, “Australia has done remarkably well. Who would have said two years ago we would be sitting here now with inflation at 2 something and unemployment at 4.1%. Not many people”. And we would agree with this, Australia has fared better than many comparable countries, even when including the surprise jump in the unemployment rate to 4.3%.

During her Annika Foundation speech, Bullock recognised that much of this success has come from a reversal of earlier supply disruptions. However, this has not been the only factor behind the normalisation of inflation and the resilient labour market . The huge expansion in public sector demand has supported the labour market more than it has added to inflation, allowing the RBA to focus on taming inflation without having to look over its shoulder at a deteriorating labour market.

The RBA’s focus is now, rightly, on preserving this success by ensuring at-target inflation is sustained and the gains in the labour market are retained. However, this may prove difficult.

The RBA will be navigating an unwind in public demand which could materially worsen the short-run trade-off between its inflation and full-employment objectives. Meanwhile, the economy may have become less sensitive to monetary policy, compounding the challenge facing the RBA.

Labour market decoupled from activity

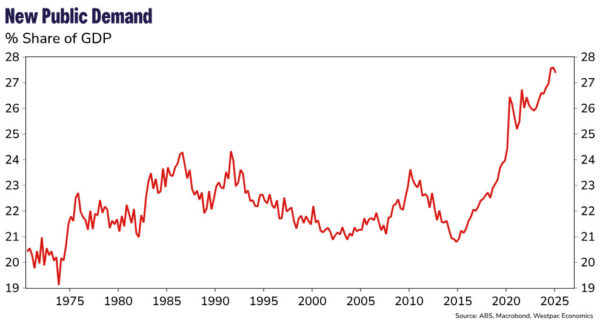

The stronger growth of public demand compared to private demand has been a persistent theme of Australia’s economic activity over recent years. Since the end of 2022 the public sector has expanded at an annualised rate of 4.0%, compared to just 1.5% for the private sector. This has contributed to a rapid surge in public demand as a share of the economy to a record high, a point we have highlighted on several occasions (most recently, here).

The strength of public sector activity has been underpinned by the massive expansion in the care economy and large-scale cost of living support for households and businesses; the latter converted some private-sector consumption, such as on electricity, into public consumption. Meanwhile, soft private sector activity has been centred on weak household consumption more broadly as high inflation, a rising tax take and elevated interest rates weighed on real household incomes. More recently, this weakness has spilled over to business investment outcomes as the boost from surging population growth has gradually faded.

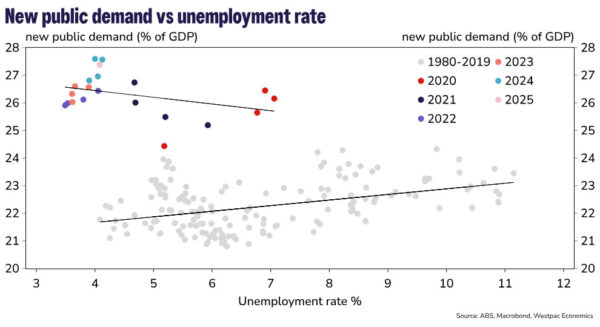

It’s historically very unusual for public demand to be so strong when labour markets are tight. Public demand tends to be counter-cyclical, increasing when the labour market is weak and slowing in the face of capacity constraints. Instead, the strength in public demand, and labour-intensive nature of the care economy, has provided significant support to the labour market as private demand (and hiring) has slowed.

Non-market sector job creation, propelled by the expansion in public demand (particularly in the care economy), has prevented a material increase in unemployment, as would normally be expected given recent weak GDP growth outcomes. In fact, the non-market sector (healthcare, education and public administration), has accounted for 95% of the growth in hours worked in the economy over the past two-years. If non-market job creation over this period had instead run at its pre-pandemic pace, the unemployment rate could be up to 1 percentage point higher today, at 5.25% – back to its pre pandemic level. This scenario assumes an unchanged participation rate and stronger employment growth in the market sector, accounting for around half of the lower non-market employment.

Inflation Impact Has Been Muted

It’s at this stage the economist in the room is quick to point out that strong growth in public demand should put undue upward pressure on inflation and make the RBA’s job more difficult. However, for the most part this has not been the case.

There’s a couple of reasons for this. First, much of the increase in public demand has been an increase and broadening of services provided on behalf of households, such as disability care, childcare, healthcare and aged care. Given these services are largely funded by the government themselves rather than households, they are not measured in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Marginal increases in demand for these services will add to inflation the government is facing but has less direct impact on consumers.

The impact of rising public demand on measured inflation has also been mitigated by the use of subsidies, which have mechanically reduced headline inflation outcomes in a similar way. The Government temporarily bore part of the burden of higher prices, reducing that faced by the consumer. These subsidies also had second round effects, reducing price gains of those items indexed to headline inflation.

There are some caveats to this. There is little argument that the non-market sector has drawn on resources from the market sector to meet the huge increase in labour demand. This is part of the reason businesses, particularly in sectors where labour is easily substitutable, continue to struggle with labour availability.

Other areas of public demand, such as the massive amount of infrastructure investment across the country are also drawing heavily on capacity in the market sector. Strong employment in the non-market sector has also supported aggregate household income growth, preventing a more significant slowdown in private consumption. These forces have added to inflation outcomes at the margin but are largely second order.

A Purple-Patch for the RBA

Overall, strong public demand has supported the labour market more than it has boosted inflation. This has been a perfect combination for the RBA as it has softened the short-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment (the ‘sacrifice ratio’) and given the Board scope to focus on its inflation objective, without being constrained by the opposite side of its mandate as the economy slowed.

However, the economy is currently in the midst of a transition. Growth in public demand is expected to slow (but remain elevated), and private demand is staging a fragile recovery. Governments are scaling back cost of living support, the care economy expansion is maturing, and thus slowing, and for the states earlier fiscal largesse is meeting the political realities of higher debt servicing costs. Meanwhile, real household incomes are growing again as inflation has returned to target, stage 3 tax cuts have paid-back some recent bracket-creep and now interest rates are on the way down. This is driving a nascent recovery in household consumption and private demand.

From Boon to Burden

As public demand slows, it could flip the economic calculus presented to the RBA. It will be a significant drag on aggregate economic activity, potentially offsetting the fragile recovery in the private sector (most recently discussed here). For the RBA, there is a related risk the labour market underperforms relative to the real economy as a slowdown in non-market sector job creation packs a bigger punch given its (now) much larger concentration. Additionally, the market sector is less labour intensive so any pick-up in market sector activity will create fewer jobs per dollar of GDP.

Importantly, the slowing in public demand is unlikely to translate into further downward pressure on inflation dynamics, at least not straight away. The earlier point that most of the increase in public demand has been in areas that are not captured in the consumer price index, is one reason for this. Another is that private demand is expected to be in the midst of a gentle recovery and dynamics in the private (market) sector are more consequential for inflation. Finally, the roll-off of government subsidies will actually have the opposite impact, mechanically lifting headline inflation outcomes, though this is likely to be deemed transitory to the extent inflation expectations stay put.

The asymmetric impact of slowing public sector growth is a tricky combination for central bankers. Instead of a world where the RBA has headroom to attend to one side of its mandate, the RBA could be faced with a scenario where they increasingly clash. The magnitude of the slowdown in public demand will ultimately dictate how heavily these objectives jar. A more significant slowing in public demand will exacerbate the trade-off for the RBA.

Monetary Policy as a Tool Might be Even More ‘Blunt’

The challenge imposed on the RBA from a worse trade-off between inflation and labour market outcomes is likely to be compounded by the fact that monetary policy will be working on a smaller share of the economy. In other words, the aggregate economy may have become less sensitive to monetary policy.

Slow moving structural changes often play second fiddle to contemporaneous economic dynamics. Economic composition is a prime example and while ‘growing the pie’ is very important, the relative ‘size of the slices’ mustn’t be ignored.

Over the past decade, Australia’s economy has quietly undergone a monumental structural shift, rivalling that of the mining investment boom. After averaging around 22% of the economy from 1975 to 2015, public demand has since exploded to a record 27% of the economy. A five-percentage point shift may not sound like much, but it’s now worth about $33 billion a quarter in real activity and is equivalent to the increase in the mining sector share of the economy during the mining investment boom.

The pandemic certainly had a role to play in this structural change, but it was by no means the only catalyst. This is a trend that was well underway before the pandemic began and has since continued at pace during the aftermath. As flagged earlier, the forces behind this compositional shift are well known: the massive expansion of the care economy, and more recently, large scale cost of living support for households and businesses. Governments are increasingly delivering support to households by purchasing or subsidising goods and services provided to households, rather than using direct income transfers.

Relatively soggy growth in the private sector over the last decade has also played a role in the rising share of public demand. Household consumption and business investment were anaemic in the lead-up to the pandemic, and outside of lockdown induced volatility, have not impressed since.

The implications of this structural change on aggregate productivity outcomes have been an important topic pioneered by my colleague Pat Bustamante here. But there are broader implications outside of productivity that have so far garnered less attention, one prominent example is what it might mean for setting monetary policy.

The RBA has spilled a lot of ink discussing the different transmission channels through which monetary policy influences the economy. But even more fundamental, is the relative size of the parts of the economy that are sensitive to monetary policy. An increase in the relative size of a less interest rate sensitive component of the economy will, at the margin, reduce the sensitivity of the whole economy to monetary policy.

It would be misleading to suggest that public demand is immune to changes in interest rates in the long run. But it’s less sensitive to monetary policy than the private sector, particularly in the context of a once in a generation terms of trade shock that’s temporarily flattered the health of our fiscal position – as is currently the case. Hence, the huge expansion in public demand has altered the economy’s relative sensitivity to fiscal and monetary policy in favour of fiscal policy decisions. (And while the reduced share of income from transfers might have made households more interest-sensitive at the margin, the expansion in public demand has been large enough to more than offset such an effect.)

Conclusion

The RBA may therefore find itself in a position where it is navigating a more challenging trade-off between its objectives with a less-effective policy tool. A larger adjustment in the labour market from slowing public demand and weaker sensitivity of the aggregate economy to monetary policy supports our view that the RBA will ultimately need to provide the economy with more monetary support.

However, the narrower trade-off with inflation will likely see the RBA remain patient in delivering support, favouring its inflation mandate at least until it no longer sees the labour market as being tighter than full employment. This will see the RBA retain policy flexibility, keep policy guidance to a minimum and continue its non-committal tone. Given this, expect less consensus in short-term meeting outcomes and a less predictable RBA – as was on display earlier this month.