Summary

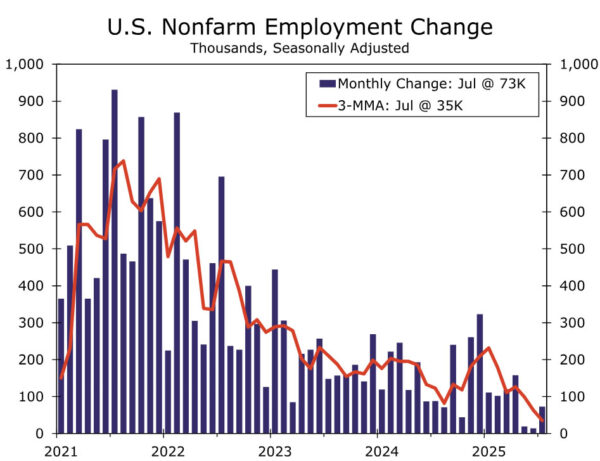

The July employment report was a dud. Nonfarm payrolls rose by 73K in July, coming in short of the consensus forecast of 104K. Employment growth was approximately zero outside the health care and social assistance industries. Revisions to job growth in the previous two months were substantial and shaved 258K off of total employment growth in May and June. In the household survey, the unemployment rate rose from 4.1% to 4.2%, but the rounding masks that the unemployment rate just barely missed reaching a cycle-high of 4.3% (4.248% to be exact). The rise in the unemployment rate came despite another tick lower in the labor force participation rate, the third consecutive monthly decline.

Coming into today’s report, our base case forecast was that the FOMC would cut the federal funds rate by 25 bps at its September, October and December meetings, with no additional rate cuts in 2026. Based on today’s data, we are inclined to leave that projection unchanged for the time being. Given both the downside risks to the Fed’s employment mandate and the upside risks to inflation, we think the Committee will move monetary policy toward a more neutral stance in the coming months to better reflect the two-way risks to the economy.

Clear Signs of Weakness

The “solid” state of the labor market described by the FOMC earlier this week looks more questionable after the July employment report. Nonfarm payrolls rose a weaker-than-expected 73K in July. More jarring, the below-consensus print came with the steepest downward net revision to the prior two months data (-258K) since May 2020. The three-month average of payroll growth was 150K coming into this report, and when incorporating revisions, the pace has lurched lower to just 35K.

Downward revisions to the prior months were broad-based. June’s initially reported 74K gain in private sector hiring was shaved down to a scant 3K rise, with notable declines in retail trade and professional & technical services. Similarly, updated information from government agencies led June’s solid 73K gain in total government payrolls to be revised down to a much more modest 11K increase. In short, hiring was not as stable as previously thought.

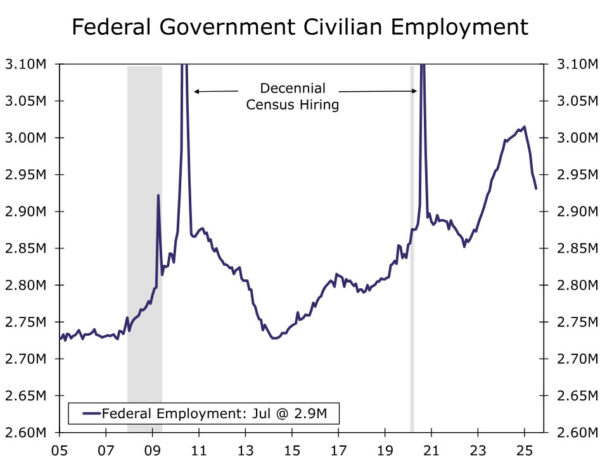

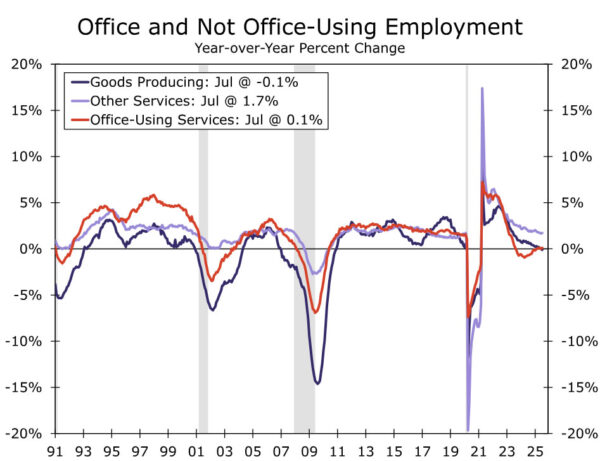

Hiring weakness across industries carried into July. The ongoing federal government hiring freeze pulled total government payrolls into the red in July (-10K), leaving employment down 84K since the start of the year (chart). Outside government, private sector hiring rebounded to a 83K gain, but the details continue to point to a narrow range of industries expanding headcount. Healthcare & social assistance (+73K) continues to be the stalwart of growth, but “white collar” jobs like professional & business services (-14K), information (-2K) and finance continue to struggle (chart). Goods related industries also remain under pressure, as shown by additional declines in wholesale trade (-8K) and manufacturing (-11K). The industry mix is illustrative of cyclically sensitive industries wobbling underneath the weight of stalling demand.

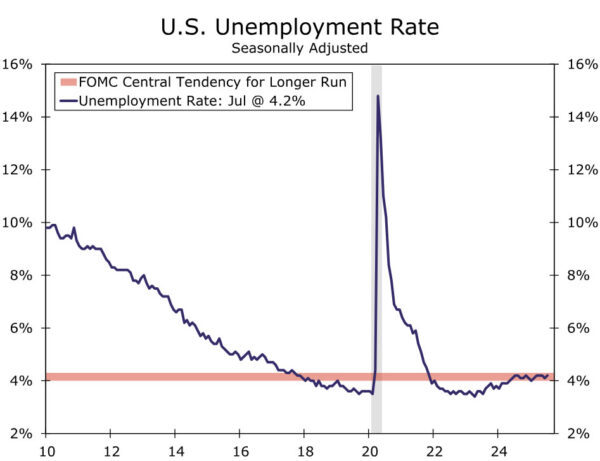

The sharp reduction in immigration this year has made the unemployment rate that much more important in assessing the health of the labor market. Amid tepid demand for workers, slower growth in the labor supply has helped to keep the labor market in balance. In July, the jobless rate ticked back up to 4.2%. That keeps it within the range Fed officials estimate is consistent with the full employment side of their mandate and moving sideways over the past year or so (chart).

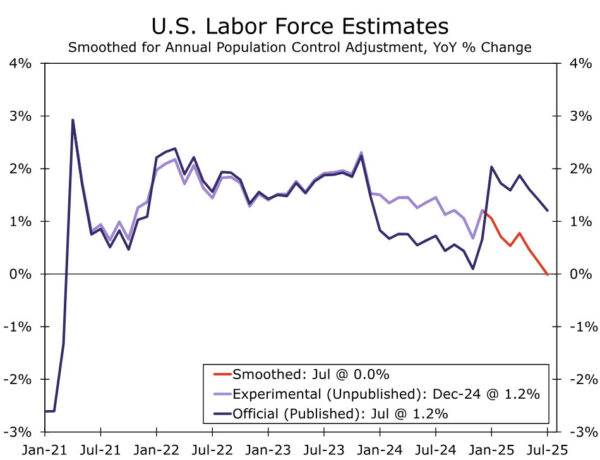

However, the increase in July looked a little more troubling underneath the surface. On an unrounded basis, the unemployment rate printed 4.248%, barely avoiding what would have been a cycle-high print of 4.3%. Moreover, the rise came amid a drop in the household measure of employment (-260K) and another decline in the labor force (-38K), not for the benign reason of more individuals looking for work. The labor force participation fell for a third consecutive month, and when smoothing through the household survey’s annual population control adjustments, the size of labor force is now unchanged from a year ago (chart). We continue to expect the unemployment rate to move a bit higher before the year is out, but we look for the rise to be limited to only another couple tenths due to the sharp slowing in labor supply growth.

Average hourly earnings rose 0.3% in the month, and the year-ago pace climbed to 3.9%. This brings it a bit more in line with the recent trend in the Employment Cost Index, which shows signs of a leveling off in wage growth this year. Even with the beat, overall compensation growth is more or less consistent with the Fed’s inflation goal once accounting for the recent trend in labor productivity, keeping us of the view that the labor market is not a source of significant inflationary pressure at present.

September Rate Cut Remains the Base Case

Coming out of this week’s FOMC meeting, Chair Powell generally characterized the labor market as solid and in a good enough position that the Committee could continue to adopt a wait-and-see approach to monetary policy. But, some Committee members, most notably Governors Bowman and Waller, stressed that downside risks to the labor market warranted a rate cut at the July meeting. Those downside risks materialized in today’s employment report, with slower nonfarm payroll growth, higher unemployment and generally crummy details under the hood.

Our base case forecast coming into today’s report was that the FOMC would cut the federal funds rate by 25 bps at its September, October and December meetings, with no additional rate cuts in 2026. Based on today’s data, we are inclined to leave that projection unchanged for the time being. Given both the downside risks to the Fed’s employment mandate and the upside risks to inflation, we think the Committee will move monetary policy toward a more neutral stance in the coming months to better reflect the two-way risks to the economy.

That said, we do not think this is the end of the debate over whether to cut rates in September. There is one more employment report between now and the September 17 meeting, and it will be critical to either confirming or dispelling the weakness seen in today’s employment data. Furthermore, there are two CPI reports between now and the next FOMC meeting. With higher prices from tariffs still slowly working their way to consumer products, an upside surprise on inflation would not be surprising. If the inflation data are hot, the FOMC will be in the ultimate bind, and the split on the Committee likely will get worse.