Major Economic Policy Proposals: What Do the Candidates Support?

In part I of our series on the 2020 election and the U.S. economy, we examined some of the key facts about the election as it currently stands. In this report, we tackle where the candidates stand on some of the major economic policy issues. We divide this into four sections: health care, taxes, international trade and infrastructure. Obviously this is not an exhaustive list of policy issues, but we believe they are the most relevant for financial markets and the economic outlook. On the Republican side, we restrict our analysis to what a second term under President Trump would look like. On the Democratic side, we restrict our analysis to the top four polling candidates at the national level: Joe Biden, Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders and Pete Buttigieg. Together, these four candidates account for a bit less than three-quarters of support in the Real Clear Politics national polling average. We would like to discuss the proposals of all of the candidates, but given that there are still 15 Democrats running according to the NY Times tracker, we need to draw the line somewhere for brevity’s sake.

If you would like to investigate the views of a candidate/policy issue not listed below, we encourage you to check out this useful issue tracker put together by POLITICO, or visit the candidates’ campaign websites. Additionally, if you would like to take a deeper dive into a candidate’s policies discussed below, we encourage you to click the hyperlinks spread throughout the text, which often lead to the candidates’ more detailed explanations of their plans.

Before discussing the policy proposals of these candidates, we believe there are two more important points to keep in mind. First, the priority a candidate places on a policy position can matter as much, if not more, than the policy position itself. Candidates naturally try to offer policy proposals on every topic imaginable, but in recent years presidents have often been able to pass only a few major pieces of legislation over their time in office. President Obama was able to push through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Dodd-Frank, for example, but fell short on carbon pollution cap-and-trade legislation. President Trump managed to overhaul the U.S. tax code, but he has not been able to successfully push through a large scale infrastructure plan. And neither President Obama nor President Trump (at least thus far for the latter) enacted comprehensive immigration reform. Thus, which policy issue is first in line for attention is critical, and something we will be monitoring closely as the field narrows further.

Second, what is proposed and what is enacted are often two very different things. Donald Trump’s initial 2015 campaign proposal called for a tax cut that analysts at the Tax Policy Center projected would reduce federal revenues by $9.5 trillion over ten years.1 A revised tax plan released by the Trump campaign closer to the election was projected by the same analysts to cut federal revenues by a smaller $6.2 trillion over ten years.2 In the end, the Joint Committee on Taxation projected that the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) would reduce federal revenues by about $1.5 trillion over ten years.3 We encourage our readers to bear in mind that just because something is proposed by a candidate does not mean the end result will be identical, or even close, to the size and scope of the original plan.

Health Care Policy: Medicare for All? ACA Booster? Or Something Else?

Donald Trump: It is a bit unclear what President Trump’s second term would look like in terms of health care priorities. After Republicans failed to fully repeal and replace the ACA in 2017, health care has largely taken a backseat to other legislative priorities. Perhaps repeal and replace could make a comeback if Republicans swept Congress and the White House. More likely, in our view, is that the Trump administration would continue to tinker with the ACA via executive action, as it has done over the course of the past few years. Some health care areas that have seen some hints of bipartisan support in the current Congress include reducing prescription drug prices and pushing back on “surprise billing.”4 These could be areas of focus for the Trump administration in a second term.

Joe Biden: On health care, the core tenet of Biden’s position is the protection and expansion of the ACA. Perhaps the biggest change to current law promoted by the Biden campaign has been the idea of introducing a public health insurance option. Under the ACA, qualifying individuals receive subsidies to purchase private health insurance plans that meet ACA qualifications; under Biden’s proposal, a public option would be offered by the federal government to compete with private insurance plans. A less expansive public option was considered back when the ACA was being written but ultimately did not make it into the final legislation. Biden has also proposed making the ACA subsidies more generous, stopping surprise billing and offering premium-free access to the public option for individuals who would be eligible for Medicaid but live in states that have not expanded Medicaid as part of the ACA.

Pete Buttigieg: Buttigieg pitches his health care plan as “Medicare for All Who Want It.” In some ways, his positions bear a resemblance to the Biden proposals outlined above. Buttigieg supports the introduction of a public health insurance option, and says of it, “This affordable public plan will incentivize private insurers to compete on price and bring down costs. If private insurers are not able to offer something dramatically better, this public plan will create a natural glide-path to Medicare for All.” Like Biden’s plan, individuals with lower incomes in states that have not expanded Medicaid would automatically be enrolled in the public option. Buttigieg also supports ending surprise billing, boosting subsidies to those who purchase health insurance on their own, capping out-of-pocket costs for seniors on Medicare and limiting what health care providers can charge for out-of-network care to twice what Medicare pays for the same service.

Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders: Both Sanders and Warren are co-sponsors of the Medicare for All Act of 2019. In short, this bill would transition the United States health care system to one where all Americans receive health insurance from the federal government. All private insurance, either bought individually or provided through an employer, would be eliminated. Furthermore, with the exception of prescription drugs and a few other small things, all premiums, deductibles and other forms of cost sharing would be eliminated.

Estimates for the cost of such a plan are varied, but one widely cited estimate by the Urban Institute pegs the total cost at roughly $34 trillion over 10 years. Medicare for All plans like the one proposed by Warren and Sanders are among the most expensive proposed changes to the federal budget. To put the $34 trillion number into context, consider that the cost of forgiving all student loan debt would be roughly $1.5 trillion, which is about the same as the estimated 10-year cost of the TCJA.

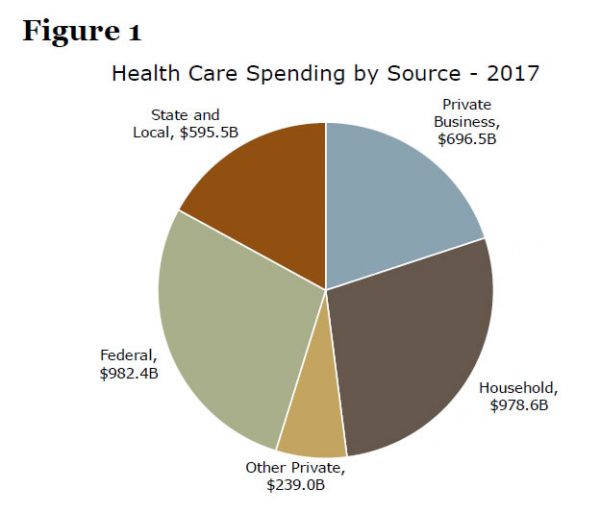

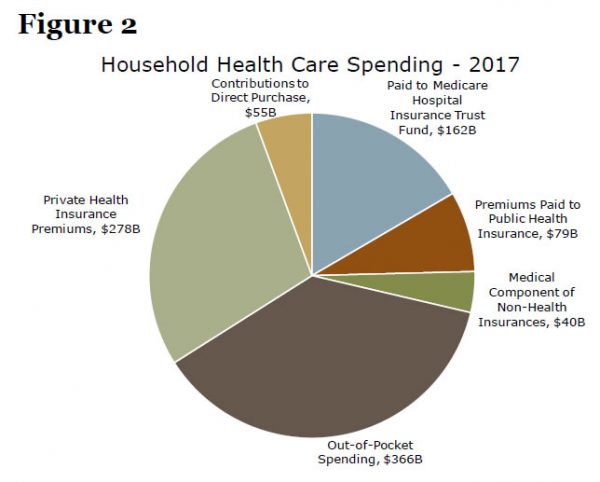

Some of this additional federal spending on health care can be paid for by simply re-routing money already spent by households and businesses to the government (Figure 1). For example, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services project American businesses will spend roughly $9 trillion over the next decade on health care for their employees. In theory, if this money were instead sent to the federal government, it would not be any additional cost to the company, all else equal. That said, even after accounting for moves like these, taxes on households would need to go up substantially to pay for Medicare for All in order to keep the federal deficit from ballooning.

Tax Policy: Tax Cuts 2.0, or a Bevy of New Taxes?

Donald Trump: A second term for President Trump would most likely be centered on some form of “Tax Cuts 2.0,” an idea that has come up periodically since the TCJA was passed at the end of 2017. In our view, the major policy aim of Tax Cuts 2.0 would be to make the temporary parts of the TCJA permanent, rather than to enact another large round of tax cuts. Although most of the TCJA changes to the corporate tax code were permanent, many of the changes to the individual and passthrough sections, such as the individual tax rate reductions and the doubling of the standard deduction, expire at the end of 2025. Republican policymakers have expressed a strong desire to make these tax changes permanent. President Trump’s second term would finish in 2024, and making these tax cuts a permanent fixture of the law would likely be a key priority before leaving office. Other proposals that could be on the table as part of Tax Cuts 2.o legislation include eliminating some ACA taxes, indexing capital gains to inflation and expanding saving vehicles like 529 education accounts. In our view, much broader, across-the-board tax cuts are unlikely unless enacted as part of a stimulus plan to deal with a recession.

Joe Biden: Joe Biden has thus far proposed a much less ambitious expansion of federal spending compared to some other leading Democratic candidates, and as such his tax proposals have not been nearly as aggressive. In addition to his health care program outlined earlier, Biden has put out an infrastructure plan (more on that later), as well as an education/job training plan that proposes policies such as doubling the maximum size of Pell Grants, increasing the generosity of incomebased student loan repayments, making two years of community college tuition-free and investing $50 billion in workforce training programs.

To pay for these programs, Biden has proposed reversing elements of the TCJA that benefited high earners and corporations. For example, Biden has proposed restoring the top marginal income tax rate to 39.6% and raising the corporate tax rate up to 28%, up from the current 21% but below the 35% rate that prevailed before the TCJA. This 28% number is in line with what was proposed in several of the budgets released by the Obama White House. Biden has also suggested taxing longterm capital gains at that 39.6% rate for taxpayers earning more than $1 million annually. At present, long-term capital gains are taxed at a maximum preferential rate of 20%, even though the top marginal income tax rate is currently 37% for single filers earning $510,300 or above. Biden also supports expanding Social Security benefits, paid for by lifting the cap on the Social Security payroll tax. At present, only earnings up to $132,900 (for 2019) are subject to the 12.4% payroll tax that is split between employers and employees.

Pete Buttigieg: To fund his health care plan, Buttigieg has proposed raising the corporate tax rate back to 35%. In addition to his health care plan, Buttigieg has also proposed a variety of other spending plans, such as spending $430 billion on affordable housing, investing $700 billion in early childhood and K-12 education and spending $500 billion to make tuition at public college free for families with income below $100,000 and reducing tuition for families earning between $100,000 and $150,000. To pay for these proposals, Buttigieg would target the top 1% of earners by raising their capital gains tax rates, as well as implementing mark-to-market taxes on capital gains. Buttigieg has at times entertained the idea of a wealth tax, but at this point in time we are not aware of any concrete proposal his campaign has on the matter. Buttigieg supports subjecting earnings above $250,000 to Social Security payroll taxes in order to expand spending on the program. Buttigieg has also floated increasing the earned income tax credit, a refundable tax credit aimed at low to moderate income households.

Elizabeth Warren: Warren has proposed some of the most detailed and far reaching changes to the tax code, in line with the aggressive expansion of federal government spending she supports, such as Medicare for All, cancelling up to $50,000 in student loan debt per borrower (with a sliding scale depending on household income), making public college free and investing $500 billion into affordable housing. Most of these proposed taxes are aimed at high-earners and corporations. Warren has promised to repeal the TCJA while also enacting a “real corporate profits tax” that would enact a surtax on U.S. corporations equal to 7% of the worldwide profits reported on a corporation’s financial statement. To finance Medicare for All, Warren has proposed a slew of changes, the full details of which can be found here. One point worth noting from it is that American companies with 50 or more employees would, instead of making premium payments to private insurers, be required to redirect that money to the federal government (this is the implementation of the “re-routing” business spending on health care discussed in the last section).

For additional financing, Warren has signaled support for a wealth tax. The wealth tax would be an annual tax on net worth above certain levels. Warren’s proposed wealth tax would start at 2% on net worth above $50 million and climb to 6% on net worth above $1 billion. Warren has also proposed taxing capital gains as ordinary income for households in the top 1% of earners, implementing a mark-to-market tax system on capital gains for the top 1% and enacting a 0.1% financial transactions tax on most stock, bond and derivative transactions. To fund an expansion of Social Security benefits, Warren would impose a 14.8% Social Security payroll tax—split evenly between employers and employees—on individual wages above $250,000. Finally, Warren also has proposed establishing a 35% country-by-country minimum tax on foreign earnings, thus shifting the United States back to a worldwide corporate tax regime, as opposed to the territorial system that was adopted in 2017 and exempts most profits earned abroad from U.S. corporate income taxes.

Bernie Sanders: Sanders’ tax proposals are somewhat similar to Warren’s, and would also be used to pay for a significant expansion of social programs, such as adopting Medicare for All, cancelling all student loan debt and making public college free. Sanders does not have quite as explicit of a plan to pay for Medicare for All as Warren, though his office did lay out some options earlier this year. These included a 7.5% payroll tax paid by employers, a 4% income-based premium paid by employees, a more progressive federal income tax system and a fee on large financial institutions, among others. Sanders supports restoring the corporate tax rate to 35% and ending full expensing of capital investment, among other aspects of the TCJA he would like to reverse. Sanders has proposed a financial transaction tax, though with more brackets than Warren’s. Sanders’ wealth tax also has more brackets: it starts at a 1% rate for net worth of $32-$50 million and eventually climbs to an 8% annual tax on net worth above $10 billion. Sanders supports taxing capital gains as ordinary income for those with income above $250,000, as well as applying the Social Security payroll tax on income over $250,000 to expand benefits for the program.

Trade Policy: Would a Democratic President Continue the Trade War with China?

Donald Trump: The specifics of what trade policy would look like under President Trump’s second term will of course depend on how trade developments unfold over the next 12 months, in particular whether a trade deal is reached with China and whether Congress finally passes the USMCA, the heir apparent to NAFTA. Even if a trade deal is reached with China (something our forecast does not assume) and USMCA becomes law sometime before the 2020 election (something our forecast does assume), trade policy would be unlikely to fully disappear from the scene in President Trump’s second term, in our view. Compliance will likely be a big ongoing issue in any U.S.-China trade deal, and some bumps along the road there would not surprise us. The United States and Europe continue to go back and forth on various trade issues, such as automobiles, and this could easily stretch past 2020. Furthermore, the president has shown a willingness to utilize tariffs as a tool to achieve other policy goals, such as his threat in May 2019 to implement tariffs on Mexico if border security was not improved. In short, we believe trade policy will likely remain a major policy issue so long as President Trump remains in office, even if the particulars shift over time.

Joe Biden: Generally speaking, the Democratic candidates have adopted a “support the goal, change the approach” strategy to with China, while generally opposing some of the trade actions taken/threatened against traditional U.S. allies, such as Canada and Europe. Among the four Democratic candidates we have examined, Biden’s comments on the campaign trail have generally been the most supportive of free trade. Biden has highlighted the potential damage done to American farmers/manufacturers by recent tariffs, and appears to be modeling his campaign more in-line with the general free trade views of President Obama. Biden, for instance, was a strong advocate for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a free trade deal negotiated under President Obama from which President Trump withdrew upon taking office. Biden also voted yes to the original NAFTA back in 1993.

That said, even a Biden presidency is no guarantee that trade policy would return to the quiet background of past presidencies. For example, Biden has more recently expressed a desire to renegotiate parts of the TPP. And the POLITICO Issue Tracker lists all four of these Democratic candidates as demanding further changes to the USMCA agreement before they can support it. Even still, when compared with the rest of the field we are examining, Biden is probably the candidate most likely to bring the trade war with China to a close, in our view.

Pete Buttigieg: Buttigieg, having never been a member of Congress, does not have an voting record on trade issues to which we can turn. He has at times expressed criticism of the U.S. tariffs on China, saying in a CNN interview in August that it’s “a fool’s errand” to think China will change the fundamentals of its economic model due to pressure from tariffs. At the same time, Buttigieg has been critical of China on other fronts, such as human rights and environmental issues, and he has expressed skepticism about joining the CPTPP (the successor to TPP once the United States left the pact). In our view, Buttigieg probably falls closer on the trade spectrum to Biden than Warren and Sanders, though all of them likely have more of a protectionist lean than the few U.S. presidents that preceded Donald Trump.

Elizabeth Warren: Warren probably falls more neatly into “support the goal, change the approach” camp, as she has generally been less supportive of traditional free trade policies than other candidates, such as Biden. During her time in the Senate, for example, she was an opponent of the TPP that Biden supported as vice president. Warren laid out a trade policy plan in July, the details of which can be found here, and included the line “while I think tariffs are an important tool, they are not by themselves a long-term solution to our failed trade agenda and must be part of a broader strategy that this Administration clearly lacks.” In the plan, Warren advocates for laying out stringent labor, environmental, and human rights rules that a country must meet as a precondition to a trade agreement with the United States.

Bernie Sanders: Sanders also has a history of supporting more restrictionist trade policies. Sanders voted against NAFTA in 1993, for instance, and opposed the TPP. On more recent trade issues, Sanders has opposed the “haphazard and reckless plan to impose tariffs on Canada and the European Union” while also “strongly support imposing stiff penalties on countries like China, Russia, South Korea and Vietnam to prevent them from illegally dumping steel and aluminum into the U.S. and throughout the world.” Like a Warren presidency, a Sanders presidency, would likely be marked by trade policy being a more important issue for the economy and financial markets than it was in the pre-Trump era.

Infrastructure Spending: Don’t Hold Your Breath

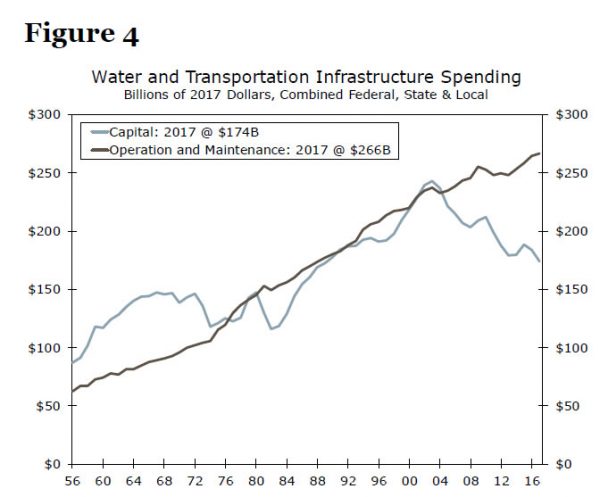

In this section, we discuss the outlook for infrastructure spending a bit more holistically, rather than on a candidate-by-candidate basis. Infrastructure is an area where there often appears to be much bipartisan agreement on the surface. Investing in infrastructure can create jobs, raise a country’s potential growth and improve the quality of life of its citizens. Indeed, after the 2016 election many analysts believed that infrastructure spending represented an area of potential common ground between President Trump and the Democrats in Congress.

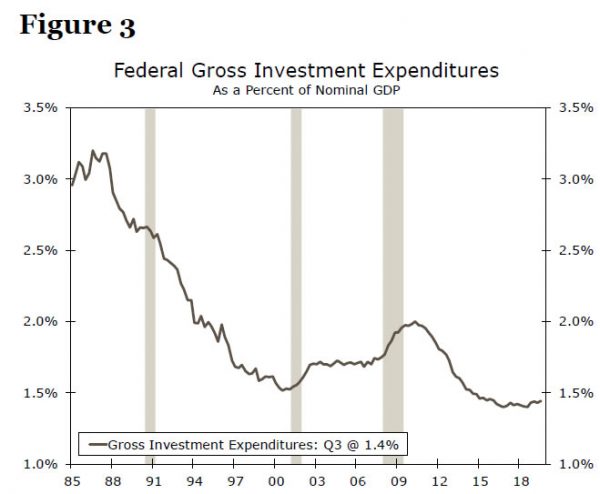

Three years into President Trump’s first term, however, there have been several false starts and not much to show for them when it comes to infrastructure spending. The main challenge is how to pay for such a program. One obvious source of revenue would be to raise the federal gas tax, which at 18.4 cents a gallon has not been increased since 1993. Republicans are generally opposed to raising this tax, however, while Democrats have concerns about its regressive nature. Policymakers could simply choose not to pay for a large investment in infrastructure spending, but if they elect to go the deficit-financed route, there are often other policies that take precedence, such as the TCJA for Republicans.

President Trump and all of the Democratic candidates we have discussed have, at some point or another, argued for increased infrastructure spending in areas such as water and transportation. Yet the proposed funding sources for these plans have been lighter on detail than in other areas, such as Medicare for All. This highlights a point that we made earlier: a candidate’s priorities are as important as the policies. A large infrastructure package could easily be paid for with higher taxes on the wealthy, but where does this leave the funding for Medicare for All? Or cancelling all student loan debt? Or universal child care? Perhaps a Biden presidency would offer the highest likelihood of a large infrastructure deal, given that his $1.3 trillion infrastructure plan is one of his more ambitious spending programs. Or, if a Democratic nominee were to make climate change their top priority, a large investment in clean energy could lead to more spending on infrastructure. But once again, this hypothetical plan would be competing for time and resources with some of the other issues already mentioned, such as health care, higher education and affordable housing.

As the field continues to narrow, we should have a better idea of what the ultimate nominee might prioritize in their first two years in office. But, at this point in time, we are skeptical a large-scale infrastructure package will be the first or second priority regardless of who the nominee is. Should a big increase in infrastructure spending take place, we believe the most likely impetus would be an economic downturn. If the economy were to slow sharply, policymakers could turn to a mix of tax cuts and infrastructure spending to stimulate the economy, as they did during the Great Recession. Outside of that scenario, we suspect there will be too many other policy priorities soaking up the finite revenue sources.

1 Nunns, J., Burman, L., Rohaly, J. & Rosenberg, J. (December 2015). “An Analysis of Donald Trump’s Tax Plan.” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

2 Nunns, J., Burman, L., Rohaly, J. & Rosenberg, J. (October 2016). “An Analysis of Donald Trump’s Revised Tax Plan.” Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

3 Joint Committee on Taxation. (December 2017). “Estimated Budget Effects of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act”.”

4 For additional background on surprise billing, see this primer from the Brookings Institution.