Highlights

- The Canadian and U.S. labour markets are rebounding from the devastating declines in March and April. So far, the Canadian recovery has been faster and more robust than what we have observed in America.

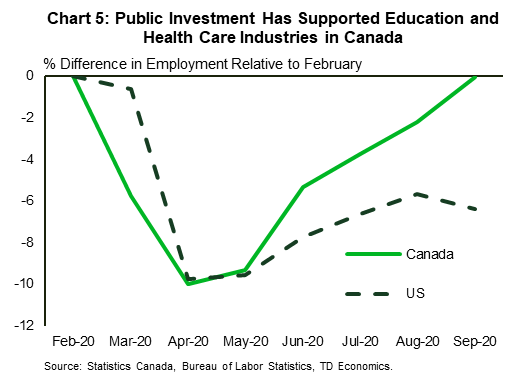

- A strong recovery in public sector employment, specifically education, is an important contributor to Canada’s lead. The sector has struggled in the U.S. due to the cash crunches faced by state and local governments.

- The recent resurgence in Canada caseloads and associated restrictions on businesses will weigh on the relative labour market outperformance, but is unlikely to erase it. The U.S. continues to face challenges on additional fiscal support and the spread of the virus.

It’s often said that when the U.S. sneezes, Canada catches a cold. However, this statement has proven false when judged against the speed of the recovery in employment during the past two recessions. The pandemic cycle is proving to once again turn the statement on its head. In a world of simple analysis, three times is a trend.

First of all, the 2001 recession was not even characterized as such for Canada. While America lost 2.1 million jobs from peak-to-trough, Canada saw steady gains in employment. Fast forward to the 2008 global financial crisis and Canada’s labour market again proved more resilient. It took about a year-and-a-half to recover job losses versus almost five years in America.

Although it’s still early days within this pandemic-induced cycle, Canada’s job market has once more gapped ahead of its U.S. counterpart, and by a fairly wide margin. As of September, Canadian employment was 3.7% below the pre-pandemic (February) level, while the U.S. was facing nearly double the deficit at 7.1%1.

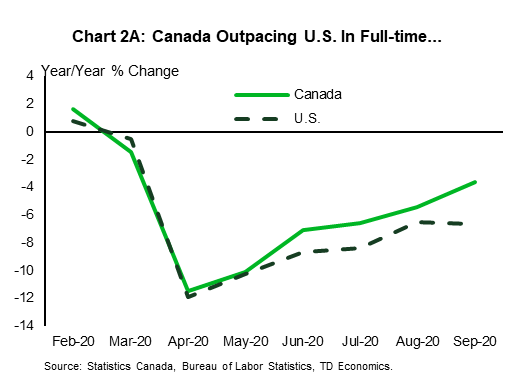

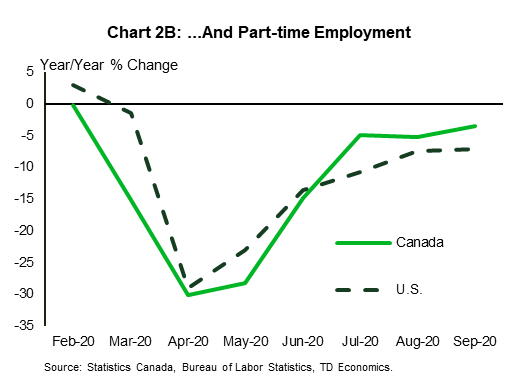

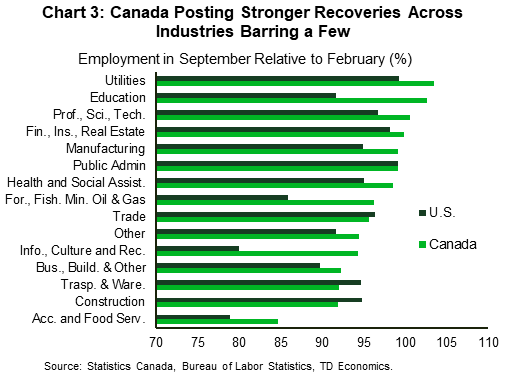

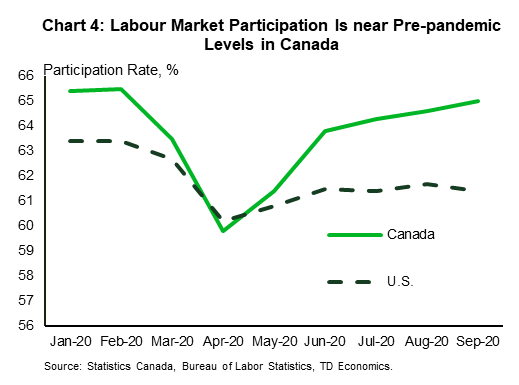

We tested the data to see if Canada’s outperformance was narrowly defined. However, most signs point in the opposite direction. Employment across full and part-time positions has rebounded faster north of the border, most industries have recovered a larger share of “lockdown” job losses and, as a result, more of the population is engaged within the labour market. This latter influence is why the speed of decline in Canada’s unemployment rate has not matched its American counterpart, giving a false signal of the health of the U.S. job recovery.

Perhaps the old adage should be rephrased to say, “When the U.S. sneezes, Canada builds antibodies”. However, let’s not get too far ahead of ourselves. It’ll be some time before we know if the antibodies will hold given the stop-and-go nature of this economic recovery and the higher sensitivity of Canadian governments to virus outbreaks. Caseloads in Canada’s largest provinces of Ontario and Quebec have already prompted targeted business restrictions at much lower thresholds than is typically the case among U.S. states. In addition, there’s a natural limit on how far the job market can recover in high-touch industries (like tourism and restaurants) in the absence of a vaccine or widely available treatment. This combination will likely cause the current employment gap to the U.S. to narrow. This economic cycle may become defined as Canada simply hitting a ceiling ahead of the U.S., rather than continuing to raise the roof.

Canada’s Labour Market Is Stronger Across Many Dimensions

No matter how you slice the data, the Canadian labour market has been on a steadier road to recovery relative to the U.S. This is true for both full and part-time employment despite similar depths of decline (Chart 2A; Chart 2B). Canada was slower out of the gate due to a more cautious approach to reopening businesses, but since June, average monthly growth in full-time employment in Canada was 1.9% m/m versus 1.2% for the U.S. Similarly, in part-time employment, Canada’s pace of gains was 7.9%, well above 5.0% south of the border.

Canada is also posting stronger employment rebounds across industries. For 11 out of 15 industries, the level of employment in September was considerably closer to pre-pandemic levels (Chart 3). The difference was especially stark in information, culture and recreation, and educational services, where the gap is above 10 percentage points2.

Furthermore, several industries in Canada saw employment move above pre-pandemic levels in September. Utilities, education, and professional, scientific and technical services all recorded full recoveries last month. Meanwhile, not one industry in America has been able to achieve this feat so far. However, it is worth mentioning that trade, construction, transportation and warehousing industries have returned employment at a more rapid pace in the U.S. relative to Canada.

The stronger recovery in Canada has meant that a larger proportion of the population has been incented to rejoin the labour market. Participation rates are significantly higher in Canada than they are in the U.S., even when accounting for the differential that existed prior to the crisis (Chart 4)3. In February, the gap in the participation rates between the two countries was 2.1 ppts. By September, it had widened to 3.6 ppts. What’s even more surprising is that Canada’s participation rate includes those aged 15, while the U.S. data includes only those aged 16 and older. The youth employment and participation rates have been particularly hard hit during this pandemic, adding an additional weight into the Canadian metric. Putting the two countries on an apples-to-apples comparison of the “core” participation of those aged 25 to 54, Canada has improved by six percentage points since April, while the U.S. has managed only a one percentage point improvement. This is in large part due to differing performances of women between the two countries.

Both male and female labour market participation rates have gradually recovered in Canada, whereas there’s been little improvement in the U.S. In fact, it’s concerning that the U.S. female participation rate declined to 55.6% in September from an already low level of just 56.1% in August. This was the first significant drop off since the lockdowns ended, offering a misleading signal in the unemployment rate improvement between the two countries. Although Canada’s rate has declined slightly more slowly than the U.S. in the past four months, the underlying dynamics of the labour market are certainly healthier north of the border.

COVID Control And Policies Offer Firmer Support To Canadian Labour Market

So, why has Canada’s labour market outperformed the U.S.? There’s not a single reason and it’s still too early to know for sure, but several contributing factors come to mind. One that immediately jumps out is Canada’s relative success in controlling the spread of COVID-19. With daily new infections flattening out during the summer months, provinces were able to gradually re-open their economies leading to steady employment gains. This is particularly evident in Quebec and Ontario, with the latter moving from stage one through to stage three of reopening from May to August, resulting in a ramp-up of jobs through the summer.

States in the U.S. showed a wider variance of outcomes. Some opened their economies very quickly (like Texas), while others took a more gradual approach (like New York). At the same time, a resurgence of the virus meant that many states either hit pause or partially rolled back reopening plans early in the summer, before relaxing them again. Generally, states with more restrictions have observed a weaker recovery. As of August, New York and California, two of the largest states with more restrictive measures, had employment around 13% and 10% below pre-pandemic levels. Conversely, Texas and Florida, states following a more relaxed approach to combating the virus, were 6% off their respective February levels4. Still, even with the lax handling of the virus, the employment recovery in these two states lags Canada.

It’s not just containing the virus. Canada’s job market is backstopped by stronger policies to encourage parents back into the workforce, while also giving Canada a head-start on that position. COVID-19 parental leave programs allow individuals to take unpaid leave for up to 26 weeks, and existing policies like paid vacation have helped keep impacted Canadians engaged with their employer through the pandemic. It appears many parents took advantage of these programs. With most schools and daycares fully reopening in September and a high share pursuing in-class experiences, parents were able to return to work. It’s probably no coincidence that employment for mothers and fathers rebounded to pre-pandemic levels last month. However, as a testament of the disproportionate weight still being borne by mothers during this cycle, the share of women working less than half of their usual hours still remains 70% higher than in February. At the same time, this is a testament that the safety net is working, allowing a partial return to hours in the face of unprecedented work-life circumstances. The alternative might have forced some parents to drop out of the labour force all together.

This dynamic may be what we’re seeing in the United States. Policymakers enacted the Families First Coronavirus Response Act in March, which provided employees up to 12 weeks of paid leave to care for children5. However, this provision only applied to employers with fewer than 500 employees. Larger businesses were left out of the legislation, and there is no federal law requiring employers to provide leave to employees caring for healthy children. This sets up a backdrop that may incent some parents to necessarily opt out of the labour market and end their relationship with an employer during the summer months and as schools reopened.

This is likely exacerbating an issue that has long plagued the U.S. labour market: weak female participation. Insufficient maternity leave and less family-friendly policies relative to peer countries had already placed female participation rates below every major advanced country before the pandemic. A strong job market was starting to improve outcomes for women in the past five years, but the gap to peer-countries persisted and now the pandemic has reversed those gains. Compare this to Canada, where maternity and family-oriented policies are considerably more generous and aligned to modern day outcomes. Female labour market participation in September was less than one percentage point off pre-pandemic levels.

Who Says The Government Doesn’t Create Jobs?

Also aiding Canada’s labour market recovery is the public sector. Education, along with health care and social assistance services, are overwhelmingly within the public domain in Canada. These sectors have added jobs at a solid clip (Chart 5). In terms of education, the demand for online schooling and smaller class sizes has risen due to the pandemic, and provinces have rushed to meet that demand by hiring more teachers. Similarly, COVID-19 has increased the need for health care workers and provincial governments have almost universally committed to boosting the size of this workforce6.

The U.S. has trailed Canada in adding jobs in both areas, especially education services. This is partly due to the fact that provinces are able to increase spending, and related deficits, in response to the health crisis, while most states do not have that luxury. Most are required by law to balance budgets, and with the pandemic weighing on revenues, many are looking at dire fiscal positions that require a reduction in spending. Early evidence of this seems to be playing out in the labour market, with state and local public education jobs declining by 281,000 in September.

In addition, Canada’s federal government has directed significant funds to provinces, to the tune of $26 billion or 1.1% of GDP, with the sole purpose of being directed to the health crisis. In contrast, states and local governments in the U.S. saw budgets come under pressure early in the crisis and we estimated back in April that they require at least $200 bn (USD) to address funding shortfalls, let alone escalating demands on the education and health infrastructure related to the pandemic. Negotiations in Congress for a new stimulus package have stalled with state and local government aid being a sticking point. Whether it’s deemed a Republican or Democrat issue, all roads lead to the same outcome – regional government policies remain expansionary in Canada and contractionary in the U.S. There is no way to avoid negative employment outcomes in the latter unless the funding model improves, particularly when you consider the knock-on effects that occur within the private sector via related contracts.

Re-Tightening In Canadian Business Restrictions Likely To Narrow Outperformance, But Not Eliminate It

Since the nationwide lockdowns ended, Canada has recovered 76% of job losses, while the U.S. has only recouped 56%. The recent resurgence in COVID-19 cases in Canada will likely weaken the recovery, but the foundation looks sturdy enough to maintain a gap with the U.S.

Canada has now entered the second wave of the virus. Provincial governments have responded by imposing restrictions on “high-touch” areas of the economy. Quebec shut down businesses such as gyms, restaurants, and movie theatres for 28 days, and Ontario followed suit. Some other provinces are also tweaking policies. This will levy further hardship on already struggling industries, and will certainly lead to additional job losses in impacted sectors. Moreover, the spike in cases could also weaken consumer and business confidence, holding back spending and investment activity, and causing employers to delay future hiring plans.

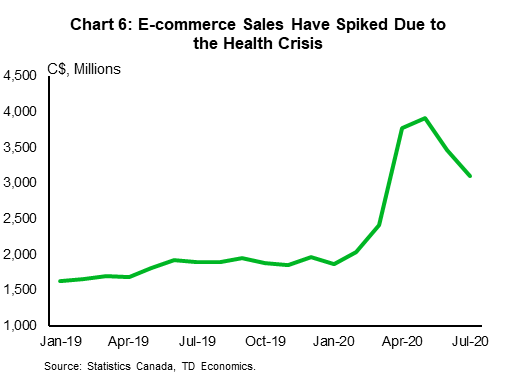

However, job openings are popping up in other industries. Some retailers are seizing opportunities provided by the pandemic to drive growth in new business segments. For example, online shopping sales have exploded since the lockdown (Chart 6), contributing to a V-shaped recovery in the warehousing industry. Retailers such as Walmart and Amazon have increased hiring in this area to satisfy growing demand. America too is seeing growth in warehousing, but the industry is relatively less developed north of the border and offers greater upside scope in that respect.

It will be difficult for the U.S. to catch up and surpass Canada’s job performance as long as COVID-19 cases remain elevated and on a worsening trend south of the border. Since mid-September, several states have again hit pause or reversed reopening plans. New York shut down non-essential businesses for at least two weeks in some counties in October, while California and Texas continue to have restrictions on high-touch industries. If COVID curves didn’t matter, then the U.S. should already be outpacing Canada on the job front based on their broadly more ambitious re-opening approach. Ultimately, the decision to reopen may not align to the foundation needed in consumer, business and employee confidence.

Additional U.S. fiscal stimulus would aid the labour market recovery, but the deadlock in Congress at the time of writing is not encouraging for a quick solution, and time is of the essence. Moreover, once an agreement is forged, there are natural delays in the execution of new funds and any needed hiring activity. More than 12 million people remain unemployed, small businesses are running out of funding provided by the Paycheck Protection Program, and, as noted earlier, many state and local governments are facing severe cash crunches. Already states such as California, Georgia, and Maryland have announced budget reductions in areas of education, courts and other public services. If Congress fails to act, labour market scars will deepen.

In Canada, fiscal stimulus continues to flow uninterrupted and well telegraphed for businesses and households into mid-2021. The Canada Emergency Response Benefit has transitioned to expanded employment insurance and Canada Recovery Benefit. For an additional twenty-six weeks, these programs will provide the exact same benefits as CERB for those still looking for a job. In addition, the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy has been extended to next summer, thereby keeping workers connected to their jobs in the medium-term. These programs and others on the business side (like commercial rent relief) likely offer the underpinning to maintain a Canadian employment recovery ahead of the U.S. through the pandemic period, even if the gap narrows.

Concluding Remarks

Canada’s faster labour market rebound relative to the U.S. is not just a phenomenon observed at the aggregate level, but also within almost every segment. Across type of employment, industry, and gender, the labour market’s speed of recovery has run ahead of its American counterpart.

Only after this crisis is in the rear-view mirror will be able to ascertain the causes of this outperformance, but at this juncture, it appears to have roots within differences in containing the spread of COVID-19, government response measures (both in the speed of execution and scope), alongside pre-existing policies.

With a second wave of infections now bearing down on Canada, a renewal of targeted government restrictions will slow Canada’s recovery in the near-term. But, as we’ve seen south of the border in its past performance, the mere act of lifting business policies is likely not a sufficient condition to propel stronger labour market outcomes alone. In addition, the Canadian government’s willingness to provide a longer term transparent and uninterrupted stream of employment and regional financial support is currently absent in the U.S., and this dynamic is already asserting itself within the labour reports on both sides of the border.

It’s still early days and we are certainly in unchartered territory. But, if the past is any indication, there’s a good chance Canada’s job market will maintain resilience through the pandemic, offering the potential for less longer-term scarring than its U.S. counterpart.

End Notes

- For most of our analysis in this note, we use data from household surveys (labour force survey in Canada, and the household survey in the U.S.) to ensure comparability.

- U.S. education figures include public sector education employees.

- While differences arise when adjusting U.S. participation rate to include 15 year-olds so that it can be better compared to Canada’s metric, the magnitudes are small and Canada still outperforms.

- These figures are calculated from the establishment survey which during the pandemic period has had a higher response rate than the household survey and is likely more reflective of actual labour market conditions.

- “COVID-19 and the Family and Medical Leave Act Questions and Answers”, U.S. Department of Labor.

- The Ontario government announced in late September that it will be recruiting 3,700 frontline healthcare workers to meet any potential surge in demand.