Summary

Although the U.S. administration has walked back its proposed tariff package on major European economies, the episode still marks a significant escalation in transatlantic tension. The direct macro impact from this in the immediate term may have been removed, but the strategic fallout is unchanged—the episode exposed deep mistrust, elevated the prominence of the EU’s Anti‑Coercion Instrument (ACI), and brought into deeper focus the fragility of the U.S.–European relationship.

What follows are thoughts around U.S. economic vulnerabilities had the EU deployed the ACI, but also how the Greenland dispute gives new momentum to a world that may be drifting apart. Rather than a simple U.S.–China split, a three‑bloc system where Europe charts more distance from both the U.S. and China could now be more realistic. Our analysis shows that three-bloc fragmentation carries heavier growth costs for Europe if access to U.S. and China‑aligned markets tighten simultaneously. And while the EU is exploring new trade partnerships and an economy less dependent on the U.S., the simple truth is that replacing the U.S. consumer is nearly impossible. So even if the EU charts new trade paths and explores deeper integration into the global marketplace without the U.S., a world where the U.S. and EU are less economically integrated raises new headwinds to global growth.

Europe’s Reaction: The Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) Threat

At the center of Europe’s retaliatory response would have been the Anti‑Coercion Instrument (ACI)—the EU’s economic “bazooka,” created to deter and counter foreign coercion. The ACI allows the EU to deploy measures including:

- Foreign investment restrictions

- Public procurement bans

- Suspension of intellectual property rights

- Tariffs, quotas, and service restrictions

Initially conceived during Trump’s first term and formalized after China’s coercion of Lithuania, the ACI has never been used. But President Macron of France has advocated its activation before—including against China—making his push to deploy the ACI well within his established playbook. The urgency for the ACI’s use has abated, but had the ACI been deployed, the U.S. economy has vulnerabilities.

Specifically that:

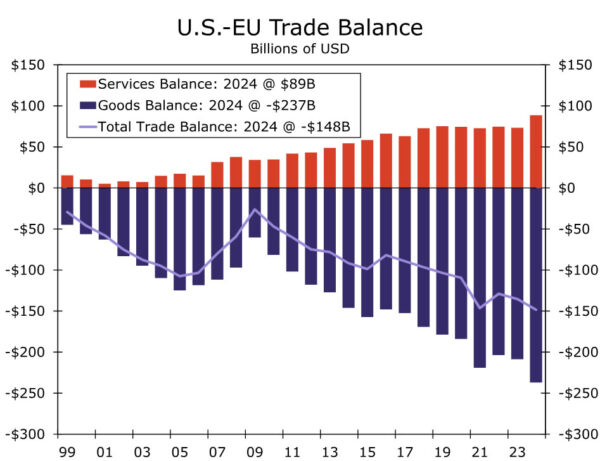

- The EU accounts for ~20% of U.S. goods exports, making the EU America’s largest high‑income market

- U.S.–EU goods trade totals ~$970 billion annually, including a $237B U.S. goods deficit

- The U.S. maintains an $89B services surplus with Europe—vulnerable if IP or professional services are targeted

Implementation, however, would have been slow: the ACI requires a multi‑stage process (examination→determination→ engagement→ response measures) that could take months to complete. A slow-moving “bazooza” retaliation option would at least provide a several-month window for cooler heads to prevail and de‑escalation to materialize.

But, focusing solely on trade volumes would understate the more strategic U.S. vulnerability. ACI measures that target intellectual property present risks that macro models do not capture. For AI, biotech, advanced manufacturing, and cloud services—sectors central to U.S. competitive advantage—EU imposed restrictions on U.S. IP could become the true economic impact of the ACI.

Had the EU pulled the ACI trigger a harsher geopolitical question would have loomed: Is the EU prepared to depend less on the U.S. in critical technologies? Before the Greenland episode, the idea was unthinkable. Now, several European officials are openly raising the prospect.

Retrench or Reglobalize? Are Greenland Tensions An Inflection Point For The EU?

The brief escalation—despite its abrupt reversal—serves as a stress test of global alignment. Greenland‑linked tariff threats didn’t just raise economic risks in the U.S. as well as Europe—they reopened a broader question we’ve been tracking for years: whether the global economy is drifting toward deeper fragmentation. What looked like a stable U.S.–EU strategic alignment now appears more conditional, and the Greenland episode pulls forward scenarios we once considered tail risks.

De-globalization has been steadily moving from a concept to a reality. The latest U.S.–EU confrontation makes a fractured three bloc world: U.S., China, EU, less abstract. If Europe retrenches from both Washington and Beijing, global growth headwinds steepen. Simulations we’ve run show that fracturing into three insulated blocs inflicts meaningfully more damage on global output than if the world carved into only U.S. and China-led blocs. And the pain is not symmetric: the EU shoulders the largest proportional hit if it loses access to U.S. and China aligned markets simultaneously.

However, another possibility exists. Rather than retrench, Europe uses this episode to deepen integration with the rest of the world, but while still keeping Washington at arm’s length. The EU-Mercosur trade agreement, a major free trade deal between the EU and select South American nations, was finally signed in January 2026. While impediments to full ratification remain, EU member states seeking friction-less trade avenues to South America is behavior that demonstrates the EU is seeking greater global economic integration. Combining the Mercosur trade deal with overtures to India and a thaw with China on EV trade shows the EU already widening its aperture.

But even in a world where the EU successfully achieves more global integration, severing trade ties with the U.S. has limits. The U.S. consumer is irreplaceable without leaning into China—something Europe has been reluctant to do. And Europe knows U.S. policy can be episodic. The Trump administration has already demonstrated a transactional approach to setting trade and foreign policy. Not to mention a willingness to tread more softly if financial markets become unsettled due to policy proposals. Pursuing structural divorce from the U.S. over what could prove to be temporary tariff and foreign policy is a heavy lift for the Europeans, and a shift that could wind up causing more economic harm than help for the EU.

Even with the de-escalation, Greenland may not just be a bilateral flare-up. It’s a potential catalyst with scope to reveal just how fragile the global architecture is, or whether a willingness to strive for new paths of economic cooperation can gather momentum. Whether the EU doubles down on a break from the U.S. and China or pursues a world where the importance of the U.S. is reduced, the direction of travel is the same: fragmentation. Reducing trade integration with the U.S. is unlikely to be fully offset by new trade relationships, and reduced EU-U.S. trade is a dynamic that places downward pressure on global growth.