This past year saw the realization of a number of key risks. Tariff talk turned swiftly into action, as the U.S. administration taxed imports on a broad range of products, from solar panels and washing machines, to steel and aluminum, to $250bn of Chinese products. Independent of that risk, breakout growth in the U.S. helped to smother the synchronous global growth theme. The resulting expectations for higher interest rates in the U.S. relative to the rest of the world put pressure on emerging market currencies. The most vulnerable and least prepared tipped into a balance of payments crisis, as capital fled to safer harbors. What followed was a slowdown in global trade flows, a dip in consumer and business sentiment, and a late-year selloff in global equity markets.

This unfolded in parallel with a host of other developments. The monetary policy environment became less supportive for economic growth after almost a decade-long expansion pushed G7 central banks to reconsider lax policies for economies that have long left the danger zone on growth. Outside of the U.S., fiscal policy has also become slightly less stimulative, with economies standing on their own legs. On the political front, a number of European countries saw a lean towards populist policies and parties, relative to establishment ones. Italy offers a recent example, with a budget impasse with the EU serving as a reminder of the tension between ideology and economic implications. The ultimate cost is being borne by Italy, where investor angst has raised borrowing costs, which will drag on future growth.

Looking to the year ahead, many of the same concerns will remain in play. After a couple of years of above-trend growth, the global economy will continue to face the gravitational pull back towards trend. Although the recent loss in economic momentum has not been extreme by historical standards, it will be important to closely monitor the interplay between event and late-business cycle dynamics that risk exaggerating market sensitivity.

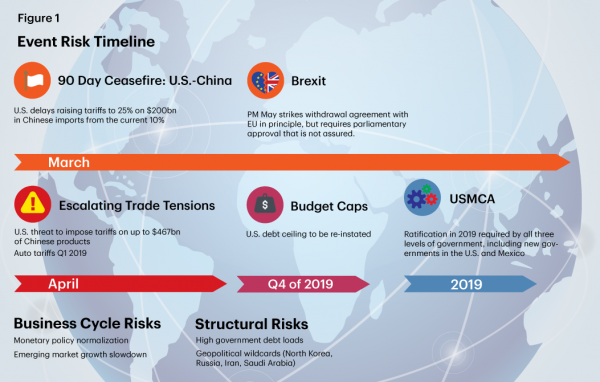

We’ve produced a timeline of the main risks in scope for 2019 (Figure 1). These risks can be bucketed into three broad categories: event, business cycle and structural. The first four noted in the text below (U.S.-China trade tensions, USMCA, U.S. government finances, and Brexit) are characterized as “event risks” that have specific timelines requiring political solutions. In recent weeks, we’ve seen a push towards resolution on the first three of these event risks, but all of the political measures so far have not succeeded in alleviating market tensions. To make matters more difficult, the countdown towards solutions is getting shorter as we head into 2019.

The next two risks under discussion fall into the “business cycle” category (monetary policy normalization and emerging market slowdown). Unlike event risks, these don’t have a defined expiration date, but are highly sensitive to the knock-on effects of event risks that can trigger the vulnerabilities they embed. The final bucket of risks falls under structural and geopolitical concerns that are constantly simmering in the background. This bucket tends not to trigger a downturn, but can certainly act as an “amplifier” once there’s a downturn in sentiment and economic momentum.

What follows is our expectation on how these risks will affect our outlook in the year ahead.

U.S.-China ceasefire doesn’t remove trade risks

The G20 summit ended with the U.S. and China agreeing to delay an escalation in trade tensions until April. Effective immediately, China has promised to import more agricultural, energy, and other products in order to mitigate the size of its trade deficit with the U.S. In addition, there’s also the possiblity of lower tariffs for some products, like autos. From China’s perspective, these promises amount to an extension of previous commitments already offered to other countries. What’s at greater stake is that these token promises do little to assuage a U.S. administration that seeks to address heavy-hitting issues related to intellectual property protection, coerced technology transfer, government subsidies, and non-trade issues such as cyber espionage. As such, the 90-day ceasefire does not dismiss the threat of eventual tariff escalation in the New Year. In fact, it is far easier for China to fulfill a request to increase U.S. product imports, than to show willingness to alter business practices.

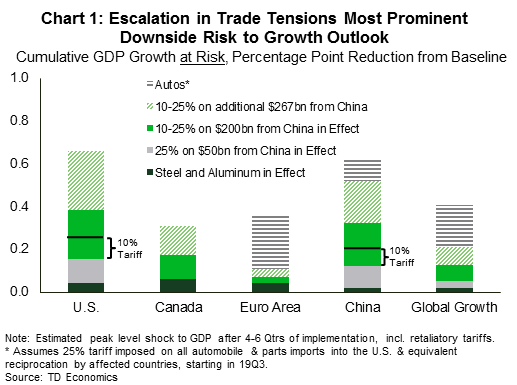

Aside from China, the threat of auto tariffs remains in play. The U.S. administration is unhappy with trade imbalances with partners such as Europe and Japan. Auto tariffs remain under national security review using section 232. Should the administration follow through with action, it would likely prove more damaging to U.S. and global growth than all other tariffs, given the global integratation of the auto sector (Chart 1).

The direct impact of tariffs alone would be insufficient to cause a recession and nimble supply chains would adjust given sufficient time. But, the nerves of financial markets are already raw, and consumer purchasing power would suffer from higher prices, alongside a potentially outsized negative impact from weaker confidence and wealth. This would be a high-stakes game for unintended consequences. Moreover, any trade war escalation would likely have policymakers at the Fed and in China reevaluating their respective economic outlooks. For the Fed this could mean delaying or ceasing the rate hike cycle, while for China it could imply looser credit conditions and more government stimulus spending.

Temporary tariffs generally don’t cause much permanent damage to the global economy, but trade tensions are now running over a year old. The extension into 2019 offers a timespan that could have scarring impacts on global investment decisions and sentiment, more generally.

USMCA (the new NAFTA)

Although an agreement in principle was reached in early October and ceremoniously signed at the G20 summit in November, the USMCA has not been ratified by the newly elected U.S. Congress. In fact, there are already whispers that the Democrats want to revisit some areas related to environmental and labor protections within the agreement. If changes do come into scope and push to far into the year, the risks of a timely ratification could shift from the U.S. to Canada, which will be facing a Federal election in October. In addition, lingering trade uncertainty well into 2019 would weigh on the Canadian and Mexican business outlook and currencies. Lastly, as the steel and aluminum tariffs have proven, the USMCA does not guarantee immunity from U.S. tariffs, with past enactments remaining unresolved.

Once the USMCA is fully ratified, it will likely not be much of a game changer for the signatory countries. The recent GM announcement of the closure of production facilities in both the U.S. and Canada is a stark reminder of that reality. Strong global competitive forces can only be partially addressed by trade agreements. This leaves the balance of risks on USMCA ratification as fairly one-sided at this stage. Any delays or obstacles would re-inject business and investor uncertainty into the outlook, but ratification would not materially change the long-term growth prospects of the three countries where the course is set via strong structural forces.

Tick-tock on U.S. government finances

A rise in global debt, both government and corporate, since the Great Recession was an expected, even prescribed, by-product of years of ultra-low interest rates and loose lending conditions. With monetary policy options virtually exhausted, governments relied on boosting spending to stimulate economic activity in the recession’s aftermath. The problem with debt, however, is that short-term gains to growth eventually give way to deleveraging pain. More formally, governments must eventually address fiscal consolidation. G7 economies are being urged by international agencies to get their fiscal house in order. As a result, fiscal policy is no longer supporting growth to the same degree it used to, and could soon drag on growth in some regions.

The U.S. is the clear exception here and this upcoming March will be an early test of the new Congress. The U.S. debt ceiling will have to be re-instated. Although we expect a compromise to occur, history suggests that Democrats and Republicans will agitate for various political agendas in the lead-up to the deadline. This is likely to inject financial market volatility amidst the mix of event risks that we’ve already described. As always, unintended consequences can occur.

Once that’s resolved, markets will turn their attention to whether Congress will lift budget caps later in the year. Senate Republicans would like defense spending boosted to address emerging risks and to maintain technological superiority. On the other side, House Democrats would prefer to cut back spending to about $700bn from the $733bn proposed by Senate Republicans. The outcome will determine whether defense spending will provide additional economic stimulus in FY2019.

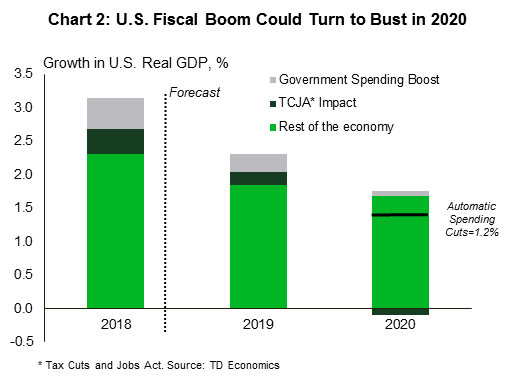

A reluctance to lift budget caps has more serious implications for the U.S. economic outlook relative to the debt-ceiling re-instatement noted above. That’s because failure to do so will cause a large step-down in government expenditures into the economy. To date, this has been adding roughly half a percentage point to GDP growth (Chart 2). In other words, the much-touted 3% growth for 2018 would look more like 2.5% in its absence. Should Congress permit budget spending to revert back to 2017 levels at the end of 2019, the impact would mark down our 2020 GDP growth forecast to a mere 1.2%.

Brexit: deal or no deal

A withdrawal agreement has been reached between the UK and the EU in principle, but still awaits parliamentary approval from the UK and EU. Recent events however, suggest the process is far from over. Next up comes a House of Commons vote, and a meaningful failure of support could trigger a reevaluation of the withdrawal agreement. A no-deal or hard Brexit could severely reduce UK economic activity after the March 2019 deadline, according to estimates provided by both the UK government and scenarios run by the Bank of England.

Deal or no deal, both near-term and longer run growth in the UK is likely to suffer as a result of leaving the EU. A Brexit deal before March outlining the terms of exit would alleviate some uncertainty, but a new trading arrangement between the UK and the EU will still need to be struck in upcoming years.

Ultimately, the long-run hit to the UK economy will depend on the architecture of the new trade agreement. The vote for Brexit was essentially a vote against the current trading arrangement between the two regions. What’s on offer from the EU in its place comes at a cost, not just the £39bn separation fee, but also with the loss of full passporting of financial services. With that comes the relocation of some business from the City to financial centers on the continent. In addition, the UK will be relegated to following EU rules and regulations rather than helping to design them. Lastly, with more friction at the borders and an uncertain future, travel to the UK, population, and labor force growth are all likely to take a hit as well. Combined, these factors forebode weaker growth in the UK, with potential knock-on effects to its trading partners.

Market jitters over policy normalization

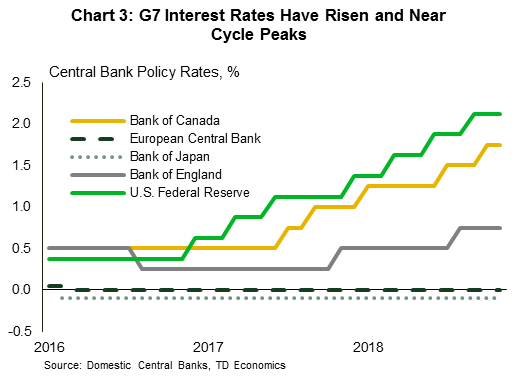

Recent events suggest that maybe central bank balance sheet normalization is not as boring as watching paint dry. The market selloff since October appears to have been at least partly driven by the prospect for higher U.S., and global, interest rates. The U.S. Federal Reserve is on the right track with interest rates given the strength of the economy and the labor market. But, there is a simple reality now in sight. The U.S. interest rate cycle is nearing a peak, which we believe will occur in 2019. This requires cautious stick-handling by the central bank to find the right level of interest rates that both supports economic growth and mitigates the risk of inflation acceleration. Past cycles have informed us that this period can result in some intensification in financial market volatility due to the debate on whether the central bank will correctly strike the right balance. And, don’t forget, their decisions are further complicated by the confluence of event-risks noted earlier that can cloud the economic outlook.

Similarly, the Fed’s peers in Canada, UK, Euro Area, and Japan are reevaluating their outlooks. With some exceptions (ECB, Bank of Japan), the liftoff in global interest rates has occurred (Chart 3). They too must walk the line between market anxiety and the risk of committing a policy error. This will keep central banks in cautious mode in terms of language and the speed of rate adjustments. If triggered, a shallow recession could be easily dealt with by most central banks using the conventional arsenal of interest rate cuts and asset purchases. However, a deeper recession would prove a greater challenge, especially for the ECB which has yet to move rates up from negative territory. Fiscal space is available, but the political environment may not be willing to utilize it (see our prior discussion on the risk from elevated government debt).

Emerging Market Slowdown

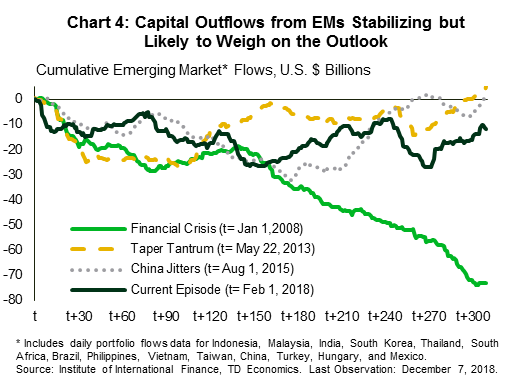

As the primary engine of global growth, emerging markets (EMs) continue to struggle with both common and idiosyncratic factors that are hampering efforts to keep growth at a long-run trend. Although capital outflows have recently eased, the high U.S. dollar and rising domestic and international interest rates will limit the ability of emerging market growth to re-accelerate (Chart 4). Debt sustainability concerns remain top of mind, particularly in countries that are in the throes of a balance of payment crisis, such as Argentina and Turkey. However, poor fiscal positions in Brazil, along with fiscal and banking sector concerns in India, raise the risk of further bouts of capital outflows and weaker economic growth as contagion fears spread.

More concerning is the risk that China’s economy decelerates more-than-anticipated over the next few years. The recent slowdown is evolving largely as prescribed by domestic policymakers, who are deliberately reining in credit growth in order to reduce future financial stability risks. But, U.S. tariffs are adding to that drag on growth, with related spillovers to China’s trading partners in South East Asia, such as Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and the ASEAN.

Slower growth in EM economies is anticipated to last for the next few quarters, after which we hope some of the near-term pressures lift. Even so, longer-term growth concerns are likely to remain. China and India account for just under 26% of global growth and face divergent challenges. China is aiming for a transition to a service-driven economy and a soft landing after an extended period of unprecedented credit-fueled investment. An engineered slowdown is always a difficult balance and will weigh on its trade partners and on the global commodity complex. On the other hand, India is unable to reform fast enough in order to achieve its full potential. When coupled with a banking sector overburdened with legacy non-performing loans, the outlook calls for comparatively strong (more than 7%) but well-below trend growth. Subpar performances in either of these large EM economies in combination with a structural slowdown in developed markets will pose challenges to faster growing emerging market economies that are heavily reliant on trade.

Geopolitical Wildcards

We end with a brief comment on an exceptionally complex topic: geopolitical outcomes. These can ultimately capture “tail-event risks”, marked by a low probability of occurrence, but a high impact should they unravel. They are purely political outcomes, and are thus difficult to appreciably embed within any economic outlook. Examples include threats of a North Korean nuclear missile launch, Russian aggression within and beyond Ukraine into Eastern Europe and the Baltics, a war with Iran, and the end of the Saudi alliance with the U.S., which could result in a positive oil price shock. Most likely these background concerns could serve as amplifiers to “event” and “business cycle” risks. But, should any one of these, in their extreme, be realized, all bets are off that the current outlook remains in play.