In last week’s note we opined that the Effective Lower Bound (ELB) for the RBA’s cash rate is 0.5% which we expected to be reached in February next year.

After that point we argued that the RBA would assess that the benefits to the currency and household cash flows from further cuts were likely to be offset by unintended consequences such as a negative impact on confidence of very low rates, financial instability, and a lowering of inflationary expectations as agents associated ultra-low rates with falling inflation.

We pointed out that our forecasts indicate that by that time, it seemed unlikely that the RBA would be satisfied that the economy was moving towards full employment, its potential growth rate, and inflation within the 2–3% band.

The RBA would also be concerned that with inflation still stuck below 2% and acknowledging that no further monetary policy action would be forthcoming, this would also encourage falling inflationary expectations as agents would sense that the RBA had run out of options.

Another risk in these circumstances might be that traders would also choose to bid up the AUD in the context of a dormant central bank.

Such a time might be appropriate for the Bank to consider unconventional monetary policies.

The Governor has publicly dismissed negative interest rates as an option but has indicated that, were the RBA to embark on a course of unconventional monetary policy, an asset purchase program would be the most likely policy option.

These programs have been used in other jurisdictions over the period 2008 to 2017.

Between 2008 and 2012 the programs were aimed at addressing disruptions in liquidity in the financial markets. They covered intervention in public sector bonds, commercial paper, agency debt, agency Mortgage Backed Securities, corporate bonds, and bank covered bonds.

From that point on, programs were aimed explicitly at monetary accommodation (with the Fed’s 2019 purchase plan to address overnight funding market issues).

In Australia’s current circumstances, given that Australian banks are flush with liquidity, any action from the RBA would be directed at monetary accommodation.

The programs were designed to work through a range of channels.

- By buying assets from any entity, the central bank would increase the level of reserves in the banking system. A direct purchase from a bank would see the central bank expand its balance sheet with a liability of increased bank reserves on one side of the balance sheet and the asset on the other side of its balance sheet. With banks now holding more reserves the objective would be to see the bank increase lending given the support of higher reserves.

- By buying the asset, the central bank would put upward pressure on the value of the asset and, therefore downward pressure on the interest rate which may pass through to other assets including private sector assets through relative value adjustments and the portfolio rebalancing channel.

- Downward pressure on the yield curve can be expected to weaken the currency to the extent that interest rates impact currencies. In addition, if the sellers of assets to the central bank rebalance their portfolio by buying an overseas asset, this will see selling pressure on the local currency.

- The central bank may also choose to purchase a foreign currency asset. This would be done by the central bank crediting the domestic bank’s reserves account in exchange for foreign currency. The domestic bank would then sell the local currency to the market in exchange for the foreign currency. That action should put downward pressure on the local currency. Once the central bank had acquired sufficient foreign currency it would purchase the foreign currency asset from the market. The end result would be that the domestic banking system would hold more domestic bank reserves boosting the liquidity of the banking system. If the central bank chose to sterilise the reserves it would then have to exchange domestic securities for reserves with the banking system. However, because the objective was monetary accommodation, it is unlikely that the central bank would choose to sterilise.

Under 1–4 the liquidity of the system is boosted by the central bank’s actions to expand its balance sheet and lift the banks’ holdings of reserves. Under 1–3 the transmission mechanism is through lowering the interest rate on the asset which may also impact the currency. Arguably, an announcement from the central bank that is was purchasing domestic assets would also put downward pressure on the currency.

Under 4 the transmission mechanism is directly targeted at the currency as the domestic banks sell the currency to fulfil the order from the central bank. The impact would be even stronger if the market signalled the actions of the central bank.

The question then becomes one of whether the stimulatory impact on the economy is greater using the reserves channel; lower domestic rates; and some uncertain currency effect, or simply the reserves effect and a more direct currency effect.

Part of the answer might be around the type of domestic assets being purchased by the RBA.

The supply of government bonds is limited. There are around $600 billion (market value) in CGS on issue but 60% are held by foreigners and a further 15% with ADI’s. The Commonwealth government is also expecting to run budget surpluses from 2019/20.

The ADI holdings are partly due to regulatory requirements, leaving, say, $150 billion in bonds on issue which might be available for purchase.

This limited free supply of bonds might mean that the RBA would not need to sell too many bonds to impact markets.

In fact, given the importance of ensuring liquidity in the bond market, if only to provide adequate signals for the futures markets, locking up a substantial portion of the available bonds on the RBA’s balance sheet might be counterproductive.

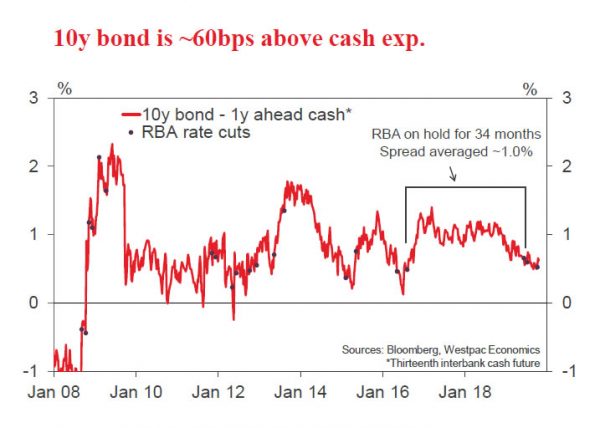

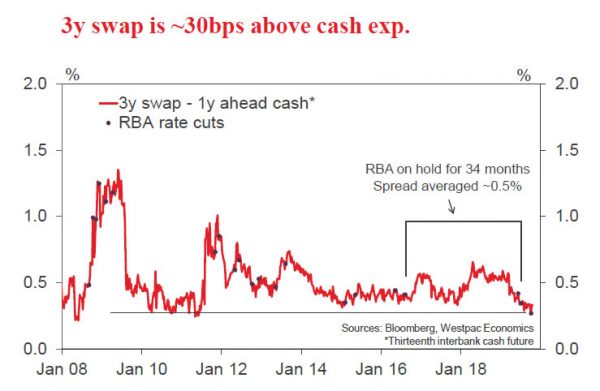

The fixed rate curve is currently historically flat (when assessed as the margin between the bond/swap rates and the expected terminal cash rate – Figures 1 and 2). That may imply that markets are already positioning for some QE activity in the bond market from the RBA. Consequently the rate impact of RBA QE in the bond/ swap market may be limited.

On the other hand purchases by the RBA of Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) are likely to provide considerable support for the monetary transmission process.

We estimate that there are approximately $77.5 billion in public prime RMBS (including banks and non-banks) on issue and approximately $19.5 billion in public non-conforming.

Within the $77.5 billion, there would be around $20.1 billion of non-bank issued RMBS; while all the non-conforming RMBS is non-bank issued.

Of the public prime issues, we estimate that around $72 billion are accepted as repo eligible with the RBA. This is despite the non–bank RMBS market not being directly regulated by APRA with ASIC overseeing responsible lending requirements, although federal legislation has been passed to provide APRA with surveillance and reserve powers over the non–bank sector.

There are many more repo eligible issues on the RBA’s repo list associated with banks’ internal securitisations, which, of course are held by the banks as security against their CLF facilities.

It is reasonable to expect that if RBA QE applied to RMBS there would be considerable stimulus to supply lowering funding spreads and providing the RBA with a sharp boost to its monetary accommodation objectives.

An international comparison to gauge the relative “appetite” of central banks for government bonds and other assets is to consider the Fed’s final QE program (QE3) which was conducted between September 2012 and October 2014.

Whereas the Fed’s earlier programs (November 2008 to August 2009 and November 2010 to June 2011) could be classified as aimed at improving market functioning, the September 2012 to October 2014 was instituted to boost monetary accommodation.

As we have discussed previously, any asset purchase program which the RBA might institute would be aimed at enhancing monetary accommodation rather than improving market functioning.

In that program, the Fed purchased a total of USD 1.5 trillion of US treasuries and MBS, over two years, in approximately equal proportions. This represented around 9% of GDP and would equate with around AUD 175 billion for Australia.

The Australian program could be proportionally smaller but still effective since the presence of the RBA in the markets, particularly if the program was not formally capped, is likely to have a disproportionate impact on markets.

The Australian program could be proportionally smaller but still effective since the presence of the RBA in the markets, particularly if the program was not formally capped , is likely to have a disproportionate impact on markets.

With the total “available” bond supply at around $150 billion and RMBS at around $72 billion (repo eligible) any program contemplated by the RBA would probably have to include other assets (other central banks bought agency bonds, covered bonds, corporate bonds, bank bonds, commercial paper and even equity ETFs) if it was to be of a scale comparable to the Fed’s last QE program.

Conclusion

We expect that the RBA has been studying asset purchase programs but is not imminent.

It will assess the economy’s progress towards the inflation target, full employment, and trend growth in 2020 once it reaches the ELB which we assess to be a cash rate of 0.5%.

While there are limits on the availability of appropriate assets, there would be scope for the RBA to adopt a purchase program that would include government bonds, RMBS, and, at least, other corporate bonds, including bank bonds. Some assets are likely to enhance the monetary accommodation objective more than others.

The additional question of purchasing foreign bonds which would have a more direct impact on the AUD, (seen as a key part of the transmission mechanism by the RBA) is more controversial but certainly should not be overlooked particularly if the AUD comes under unwelcome upward pressure.