Executive Summary

- As we come to grips with the unfolding COVID-19 outbreak and the various ways it could impact the economy, this report looks at potential shock absorbers for supply chains and considers how the outbreak may influence U.S. trade policy.

- Make no mistake, the outbreak is a negative for supply chains and will cast a long shadow on output, but there are some mitigating factors that bear consideration.

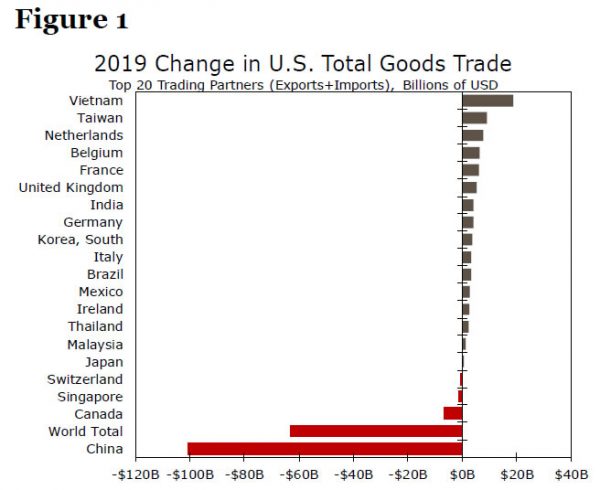

- First is that increased U.S. imports from Vietnam (which has been spared in the outbreak so far) have offset some of the diminished U.S. trade with China. The production shift may cushion the blow for U.S. manufacturers that in the past might have relied solely on China.

- Second, the possibility of U.S. companies having brought forward shipments in an attempt to get ahead of previously scheduled tariffs has, at least in part, helped boost manufacturing inventory ratios, and in effect provides some cushion to supply chain disruptions.

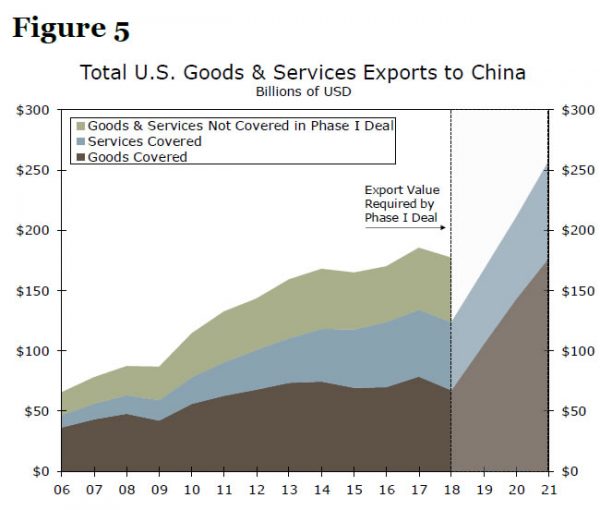

- Finally, the outbreak also has implications for U.S trade policy. The promised Chinese purchases of roughly $200 billion of U.S. goods and services, agreed to in the Phase I trade deal, was already going to be a challenging undertaking, but the outbreak, and its effect on China’s economy, make those purchase targets even more difficult to achieve.

Could Vietnam Cushion the Blow?

In a series of recent reports looking at COVID-19, we have made the case that there are supply chain implications for American businesses if Chinese factories shut down for any significant length of time.1 We have also extended our analysis for both Japan and South Korea where the virus has reportedly spread. Another link in this supply chain that bears consideration is Vietnam.

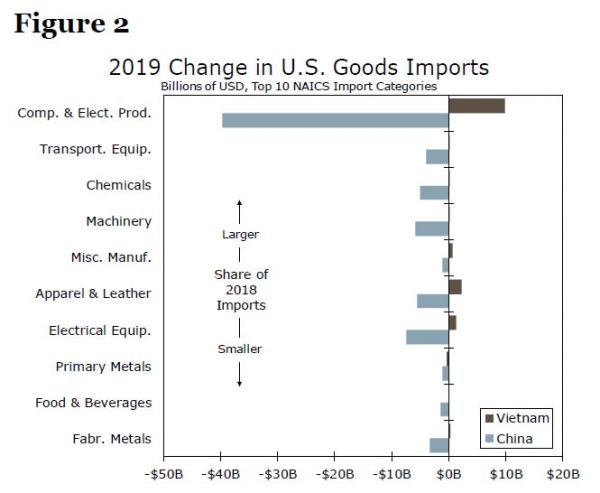

For example, U.S. imports from Vietnam rose in 2019 for key intermediate goods categories like computer & electrical products, which shot up $9.9 billion even as Chinese imports in this category showed a steep $39 billion decline.

The apparent surge in exports from Vietnam over such a short period has been met with skepticism about the authenticity of Vietnam as the true source for these goods and not just a backdoor for goods that are still being made in China. Vietnam’s net swing of $18.7 billion in the trade of goods with the United States is larger than the next two net gainers (Taiwan & Netherlands) combined. But, despite skepticism about Vietnam’s stepped-up role, a rise in Vietnamese industrial production last year suggests some of the production transition is genuine.

To the extent that Vietnam is indeed the bona fide manufacturer of all these goods, the production shift may cushion the blow for U.S. manufacturers that in the past might have relied solely on China. Numbers on the COVID-19 outbreak suggest that Vietnam has been largely spared in the current outbreak (at least for now); its comparatively scant 16 reported cases are even fewer than the 57 reported cases in the United States. That said, more recent output figures there are not too encouraging. The latest data showed that Vietnamese industrial production fell 11.8% in the month of January and is now down 5.5% over the past year.

How Trade War Worries May Act as Another Buffer

The trade war has had mixed effects on U.S. economic growth, the most impactful of which may be the cloud of uncertainty it has created particularly in the manufacturing sector which was showing signs of weakness long before the COVID-19 outbreak. But it is also fair to say that the trade war, in a sense, has left U.S. businesses in a better place to absorb supply disruption from China at least in the short run.

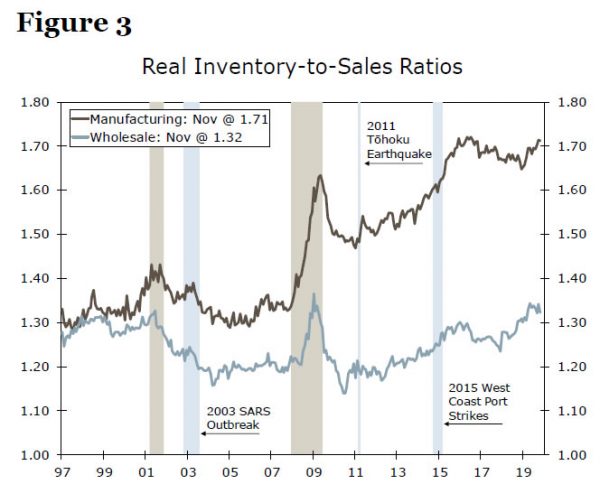

Anecdotal reports of U.S. companies bringing forward shipments to get ahead of potential tariff increases is corroborated by elevated inventory/sales ratios in a number of manufacturing industries (Figure 3). Note that at present, the inventory-to-sales ratio for manufacturers is higher than it was during prior global supply-disruption events.

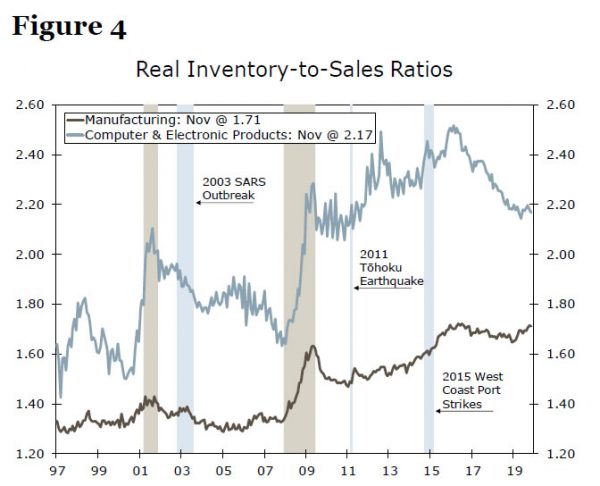

That may buy some time for U.S. importers to find alternate sources for some goods, but it offers cold comfort for businesses that rely on a product made exclusively in China, which is sometimes the case for computer & electronics products. The inventory-to-sales ratio here suggests businesses in this industry are sitting on smaller stockpiles than they typically have in recent years (Figure 4). That said, the computer & electronics products ratio is still higher than a decade ago.

Will COVID-19 Give China Cover for Missing Purchase Targets?

While the trade war may play an unexpected role as a potential buffer to supply chain disruption due to COVID-19, one of the big victories in the trade dispute may prove to be more elusive as a result of the outbreak. The centerpiece of the Phase I trade deal was a commitment by China to buy an additional $200 billion of various goods and services over the next two years. As a recent report from the Petersen Institute points out, those targets may be tough to reach.2

The details set out in the agreement have China increasing its imports of certain products from the United States by $76.7 billion in 2020 and by an additional $123.3 billion in 2021 from its pre-trade war 2017 balance of roughly $134.2 billion (Figure 5). That is a 92% increase in imports over the next two years from 2017 levels. But the true starting point is actually much lower than that. Goods exports to China declined over the past two years, as many of the goods covered in the agreement were exposed to tariffs.

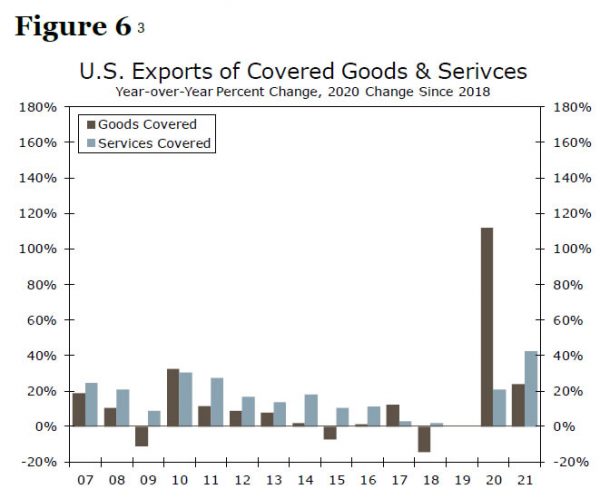

U.S. exports of the goods in question dropped 14% in 2018. That swamps the scant 2% increase in service exports over the same period (Figure 6). Using 2018 as a baseline, China has agreed to increase these imports from the United States by 70% over the next year alone. Because 2017 was a high watermark in terms of U.S. goods exports to China, the expected goods increase is even more stark, with China agreeing to more than double its 2018 import value.

While a mere doubling in imports of particular goods alone seems ambitious, the ability to achieve these figures is exacerbated by COVID-19. Production halts and travel bans across China are expected to weigh on Chinese consumption for as long as the virus outbreak remains. With the virus continuing to spread, a slowdown in the service sector will likely weigh on imports and decrease the possibility of China holding up its end of the agreement.

Conclusion

Although trade war uncertainty has weighed on U.S. business spending, in some ways, the trade war has left the U.S. economy in a better position to whether supply chain disruptions, at least in the short-run. America’s reliance on China for important import categories has declined over the past year, as Vietnam, among other countries, has taken up some of the lost share previously coming from China. The possibility of U.S. companies having brought forward shipments in an attempt to get ahead of previously scheduled tariffs has, at least in part, helped boost manufacturing inventory/sales ratios, and in effect provides some cushion to supply chain disruptions. That said we fully expect supply disruptions may manifest themselves in U.S. output.

The “good news” of the trade war, that China has agreed to nearly double its imports of particular goods and services from the United States over the next two years, is now very much in peril. While such targets were previously thought as improbable, the hit to Chinese imports from the U.S. due to the virus likely makes this target even more difficult to achieve.

1 Please see our recent commentary on COVID-19 here.

2 Brown, Chad P. “Unappreciated hazards of the US-China phase one deal.” PII. (January 21, 2020).

3 We use 2018 as a baseline for our 2020 year-over-year percentage change calculations since U.S. services trade data is not yet available for 2019.