Summary

Key Themes

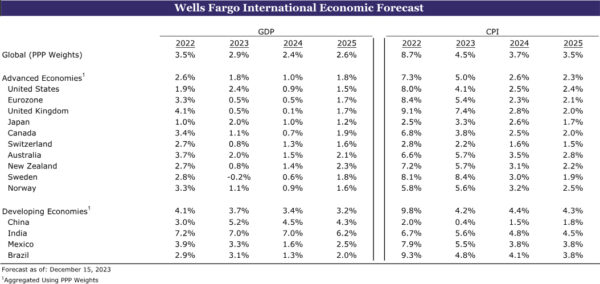

- As we head into 2024, we are downbeat on the prospects for global GDP growth. In our view, the global economy is likely to experience a period of below-trend growth in 2024, with the global economy expanding just 2.4%. Growth prospects are to be restrained by a U.S. economy likely to experience a mild recession in mid-2024, recessions in the Eurozone and U.K., as well as a Chinese economy that is decelerating amid structural challenges. We do, however, believe select economies can outperform and grow at above-trend rates. Asia, in particular India, should be the region and economy that stands out from a growth perspective.

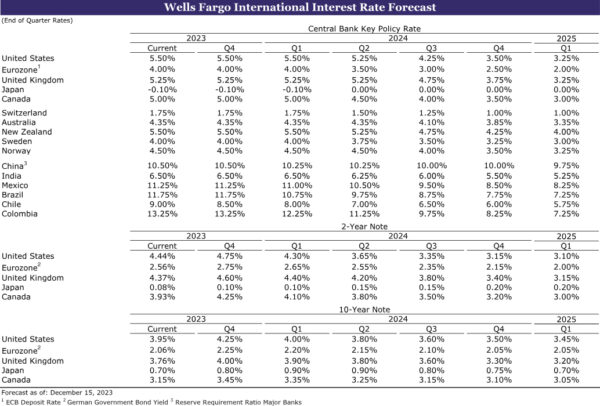

- With the growth outlook less-than-robust and inflation receding quickly, we expect many of the world’s central banks to begin, or continue, cutting interest rates in 2024. In the advanced economies, we believe most G10 central banks will start cutting policy rates in Q2-2024; however, risks are tilted toward earlier easing as inflation falls back toward targets. Emerging market central banks that have initiated easing cycles already should continue cutting, while those that have been more prudent should start in the coming quarters. With that said, we believe policymakers in the developing world will still act cautiously when considering easing monetary policy.

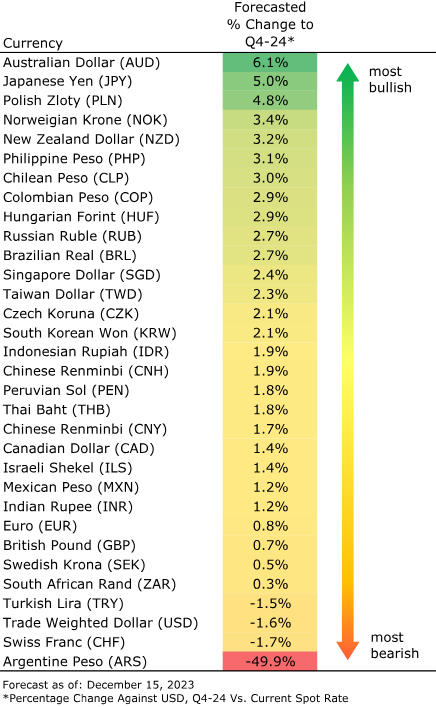

- Our views on currency markets have not materially changed. We continue to believe that with major central banks on hold for the time being, relative economic outperformance will be the catalyst for one last bout of U.S. dollar strength. As the U.S. economy falls into recession and the Fed begins easing monetary policy, we believe the dollar can depreciate against both G10 and emerging market currencies. We believe the economic and monetary policy backdrop in 2024 will be consistent with emerging market currency outperformance, and in our view, select currencies in Latin America and EMEA can perform most strongly.

- Geopolitics and elections add a degree of uncertainty to the global economy and financial markets in 2024. The Russia-Ukraine conflict is still active, and the Israel-Hamas war does not appear to have an end in sight. Geopolitical developments can lead to further deglobalization, and possibly a fragmenting of the global economy, both of which can place new downward pressure on global activity. In addition, multiple meaningful elections will take place in 2024, and while not all will be affected by geopolitics or create local financial market volatility, select votes can create disruption and alter the global political landscape.

2023: A Year in Review

A close to a year is always a good time for reflection. That is, to reflect on the performance of the global economy, financial markets and any unforeseen developments that occurred over the past 12 months. We communicated a rather pessimistic tone in our 2023 outlook; however, the global economy proved to be more resilient than we expected. Over the course of the year, U.S. economic activity remained strong and the American economy avoided recession, with many thanks to the staying power of the consumer. Despite a deceleration at the end of the year, Europe also fared better than expected. Energy crisis conditions were avoided after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as an unseasonably warm winter bailed out the Eurozone and United Kingdom. And in China, “zero COVID” policies were lifted after nearly three years, and while activity in China remained somewhat sluggish, growth prospects improved as a result of the end to pandemic mobility restrictions. Resilient U.S. spending, some luck in Europe and policy adjustment in China were the drivers behind our decision to lift our original forecast for global recession to occur in 2023.

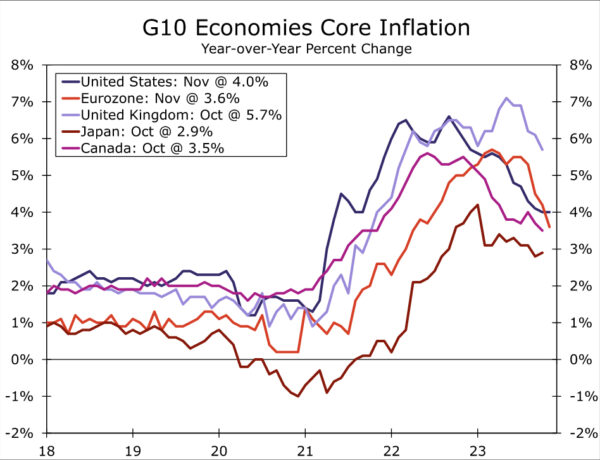

Elevated inflation continued to be a major concern in 2023. Earlier in the year, economies around the world were hit with among the most rapid price growth in decades. As worries around price growth were justified, decisive monetary tightening was delivered by many of the world’s major central banks. In most cases, policymakers delivered sizable clips of interest rate hikes that outpaced market participants expectations at the beginning of the year. “Higher for longer” became a dominant theme in financial markets, with institutions such as the Federal Reserve opting to bring rates into restrictive territory and communicate a stance to hold policy steady until disinflation was well under way. This prudent central bank policymaking proved effective as inflation is within earshot of central bank targets in many G10 economies, including the United States and Eurozone. Even as inflation concerns receded, price growth was still the most important data point for financial markets in 2023. With inflation on a downward trajectory around the world, the question markets sought answers to eventually became: When does the pivot to rate cuts happen? While the Fed did not explicitly give guidance on when more accommodative monetary policy would start, FOMC policymakers seemingly laid the foundation for a 2024 pivot at their December meeting.

2023 will also be remembered as a year of geopolitical strife. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine continued over the course of the year, leading to a longer-lasting conflict in Eastern Europe than imagined and still no end seems to be in sight. New geopolitical shock waves were also felt this year as Israel declared war on Hamas in early October. The humanitarian crisis in the Middle East has been devastating, with tens of thousands of casualties and millions more displaced. While the war may not boil over into a broader regional conflict, an end to the Israel-Hamas war also does not seem to be imminent. Hovering in the background, but still very much a concern, are persistent U.S.-China tensions. Trade and investment restrictions intensified, while a mysterious “spy balloon” escalated tensions between the world superpowers. On the other hand, President Xi coming to the United States in an attempt to mend relations yielded marginal benefits to the relationship, although a meaningful thawing of frictions has yet to be achieved. With Taiwan and U.S. elections on the horizon, political posturing, or worse, between the two nations is likely to remain a key theme going forward.

Many of the themes that drove the global economy and financial markets in 2023 will be present again in 2024. The health of the global economy, the monetary policy response, and the direction of geopolitics and local politics should come to move markets and shape economies in the coming year. 2023 had its challenges, but overall, the global economy and risk assets performed well this year. 2024 could see more challenges, particularly as the global economy enters a period of below-average growth and the political calendar is full. As we head into a more challenging economic environment and uncertain political climate, the global economy may struggle to “weather the storm” once again. As conditions evolve over the coming year, we encourage readers to stay in touch and ask how we can help. We hope everyone has an enjoyable holiday season, and as always, stay safe and stay healthy.

Nick, Brendan & Anna

Global Economic Growing Pains

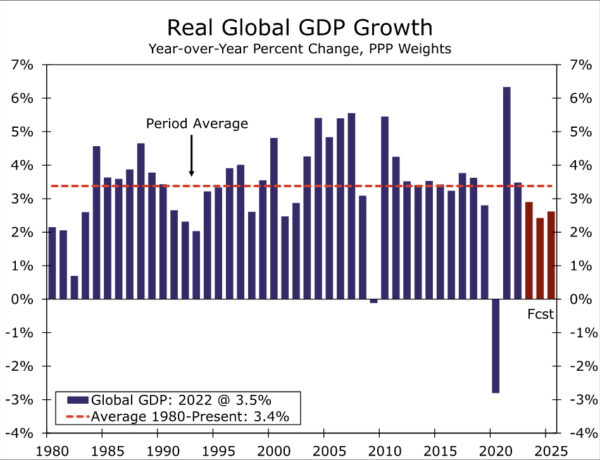

For most of the past five decades, the global economy has been successful in “weathering the storm.” Not just a storm, but storms. Double-digit inflation during the 1980s, military conflict in the 1990s, the dot-com bubble and geopolitical shocks in the early 2000s, the ’08-’09 Global Financial Crisis, COVID and everything in between that caused outsized economic disruption. Despite shocks like these, the global economy has held up quite well over time. While the global economy has ebbed and flowed in response to certain events as well as the normal business cycle, global GDP growth has averaged around 3.5% per year since 1980. However, in just the past few years, the global economy has been hit by many of the same events it experienced during the past five decades. Another bout of elevated inflation, military conflict in Europe and the Middle East, theories of another bubble in the technology sector, escalating worldwide geopolitical tensions, and regional bank failures in the U.S. and Europe have all occurred in the past two years. Tack on aggressive central bank monetary tightening and clearer structural growth challenges in China, and these simultaneous shocks are placing downward pressure on the prospects for global growth. In our view, weathering the storm may be more challenging this time around. We believe the long-run ~3.5% average global growth rate is unlikely to be reached in 2024, and instead, we believe the global economy is likely to grow at a below-trend pace of 2.4% next year (Figure 1).

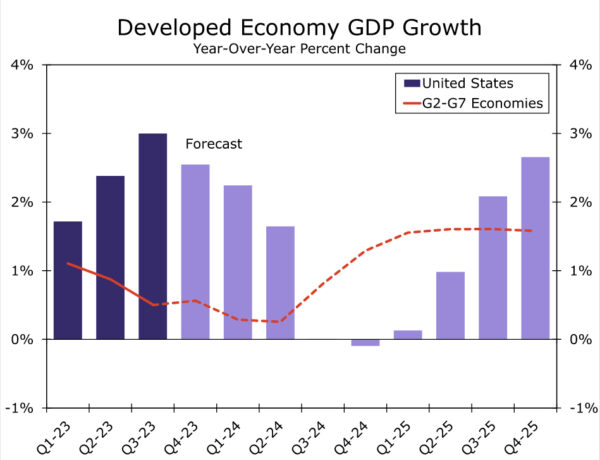

2024 is likely to be characterized as a low-growth environment. While technically we are not forecasting global recession (i.e., global growth below 2%), we do expect many economies around the world to experience downturns. In our view, the U.S. economy is still likely to enter recessionary conditions by the middle of next year. We believe delayed effects of Fed interest rate hikes and balance sheet reduction, a pending consumer spending slowdown and tighter bank lending policies will result in a mild U.S. recession in 2024. With that said, the probability of the Federal Reserve orchestrating a soft landing has risen. Tighter monetary policy has not meaningfully disrupted economic activity up to this point, while softer inflation is leading to improved real incomes and household purchasing power. Financial conditions have also eased as U.S. Treasury yields have retreated, also boosting the likelihood that a soft landing can be achieved. While the outlook for the U.S. economy has improved recently, growth prospects in select peer G10 economies have worsened heading into 2024. Eurozone GDP contracted in Q3-2023, and with manufacturing and services sentiment indices in contraction territory through December, we expect the economy to also decline in Q4 and for technical recession—defined by two quarters of consecutive contraction—to form. We also forecast technical recession in the United Kingdom. Elevated inflation and high Bank of England interest rates are likely to place downward pressure on the U.K. economy next year. In fact, we expect the U.K to experience a deeper recession relative to the U.S. and Eurozone, and we forecast the British economy to grow just 0.1% next year.

We expect emerging market economies to be more resilient relative to advanced economies in 2024. The recessions we forecast in the G10 may not be as present in the developing world, and the clearest economic outperformers are also likely to be found in the emerging markets. To that point, we forecast G10 economies to grow 1.0% in 2024, down from 1.8% in 2023. On the other hand, we believe developing market economies can grow 3.4% next year, only slightly lower than the 3.7% growth experienced in 2023. Not only do we expect EM economies to grow at a faster pace than advanced economies, but the delta between 2023 vs. 2024 aggregate GDP growth rates is much smaller in the developing markets, a signal of relative economic strength and resilience in the emerging economies. As far as outperformers, we expect Asia, more specifically India, to be the region and country where growth prospects will be most robust. India’s economy likely grew 7% in calendar year 2023, and we expect a similar growth profile in 2024. Many global and local developments—such as geopolitical conflict, softer foreign demand and aggressive central bank monetary tightening—that are likely to contribute to slower activity abroad are not particularly relevant to India. As a result, India can be one of the fastest growing economies in the world next year. Regional economies such as Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines should also represent relative economic outperformers. But within the developing world, select regions and economies could experience more lackluster growth, and in certain cases, recession. In our view, Latin America is likely to be the region that acts as a drag on overall EM and global growth. Economies such as Brazil, Chile and Peru are examples of where high interest rates, reduced fiscal support and elevated political risks are likely to weigh on activity. While Latin American economies were resilient in 2023, we believe the probability of recession for these countries will remain elevated in 2024. However, not all of Latin America is on the brink of recession. Mexico is a clear outlier, and even though growth should slow as the U.S. economy decelerates, the positive impacts of nearshoring as well as local political and financial market stability should prevent recession from materializing.

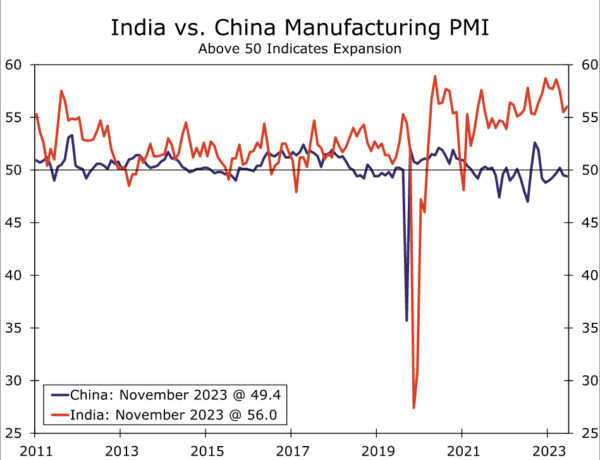

While India and broader Asia should be the most apparent growth outperformer next year, there are still troubled economies percolating across the region. The one challenged economy that garners the most attention, and rightfully so, is China. In our view, long gone are the days when China’s economy would, and could, grow at double-digit growth rates. Instead, China’s economy is now defined by structural issues—such as an aging population and shrinking work force, a real estate sector crisis, an overleveraged non-financial corporate sector, deflation and declining household consumption—that should place downward pressure on growth rates for an extended period of time. On top of structural, not-easy-to-fix challenges, China has been at the center of multiple geopolitical controversies and operating under an uncertain policy mix. Economic struggles combined with foreign and domestic policy uncertainty is slowly resulting in China being replaced in global supply chains and making investors reconsider whether China is an attractive destination for capital deployment. Both of these dynamics can compound China’s structural economic slowdown. In fairness, Chinese authorities recognize impediments to growth and have adjusted monetary and fiscal policy settings in response. Lending rates and bank reserve requirement ratios have come down in 2023, and policymakers recently hinted that more fiscal support could be offered in the near future. On the margin, more accommodative policy can support China’s economy; however, fiscal support directed at the real estate sector and easier monetary policy will not fix demographic issues, rising geopolitical tensions, low consumer confidence or sluggish domestic consumption. This is why we believe China’s economy will slow sharply and experience growth of just 4.5% in 2024, and also that regional power and economic dynamics may be shifting in India’s favor. India is a prime candidate to replace China as a manufacturing hub (Figure 2), while foreign direct investment and portfolio flows seeking exposure to Asia have trended toward India and away from China over the past few years. More favorable economic fundamentals and recent trends also have India being considered for sovereign credit rating upgrades. Conversely, China’s economic challenges and weakening public finance position resulted in a revised negative credit rating outlook from Moody’s that could spark further capital outflows should a rating downgrade be delivered in 2024.

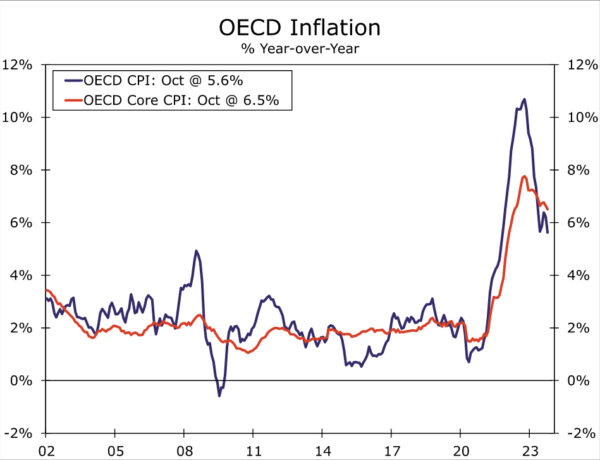

Invitations to the Central Bank Pivot Party Are Out

Much like the slower global growth we forecast for 2024, we also anticipate a further softening in global inflation. Unlike slowing growth, decelerating inflation represents a more welcome and favorable trend. Similarities between the global growth and global inflation relationship also exist. We noted the divergences in growth trends across major economies, and that same divergence trend is also present in the context of inflation. OECD economies, which are largely comprised of the advanced economies, show headline inflation decelerating to 5.6% year-over-year through October, down from a peak of closer to 11% in early 2023 (Figure 3). OECD core inflation slowed more gradually to 6.5% year-over-year, but is also past its peak. On a country-by-country basis, increasingly encouraging inflation developments have materialized, with G10 economies in particular registering pleasant surprises. In the Eurozone, November core inflation slowed more than forecast to 3.6% year-over-year, while the three-month annualized pace of underlying inflation is trending at a pace broadly in line with the European Central Bank’s inflation target. Similarly, U.K. inflation slowed more than expected in October although, at 5.7% year-over-year, the core CPI is still well above the Bank of England’s inflation target. Canada and Australia both registered sharp slowdowns in inflation in October, while Swedish inflation also decelerated in November. Point being, while inflation is still above central bank targets, G10 inflation is on a sustainable downward trajectory (Figure 4).

The inflation story in the emerging economies is, on the margin, slightly different. Inflation is slowing in many of the larger emerging market economies; however, recent trends, in select countries, have been a bit more unpleasant. In Chile, November inflation data surprised to the upside as the CPI slowed less than expected as higher food and transportation costs set in. Colombia experienced a similar development as November inflation decelerated, although core CPI unexpectedly edged higher. A sharp devaluation of the Argentine peso should also fuel inflation significantly higher in the Latin American country. Outside of Latin America, Reserve Bank of India policymakers expressed caution toward the disinflation process and warned that inflation is likely to tick higher in the coming months due to higher food prices. Additional emerging Asia central banks have also cautioned that trends in food costs can firm inflation in the near term. All told, we forecast global CPI inflation of 3.7% in 2024, down from an estimated 4.5% in 2023. However, we believe the global disinflation process will be mostly led by slower inflation in the advanced economies. To that point, we project advanced economy inflation of 2.6% next year, down from a forecast of 5.0% in 2023. For the emerging economies, we actually anticipate some acceleration of inflation to 4.4% in 2024, from 4.2% this year. Granted, while short-term inflation trends in the emerging markets are not as favorable as the G10, the acceleration in EM inflation is due to our view that China’s CPI will begin to normalize in 2024. As of now, we believe year-over-year inflation in 2023 will be 0.5%. Fiscal stimulus and base effects should push China’s CPI up closer to 1.5% in 2024.

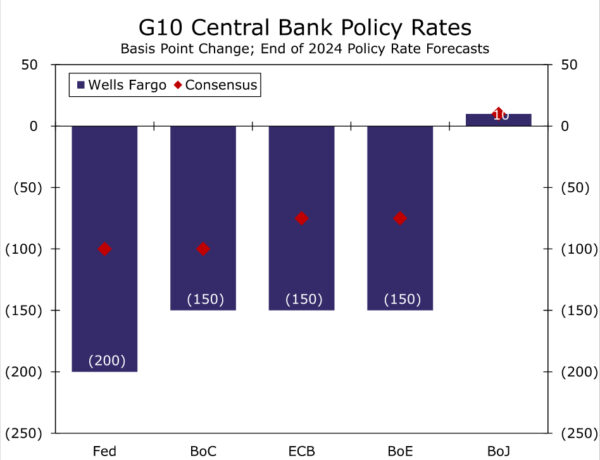

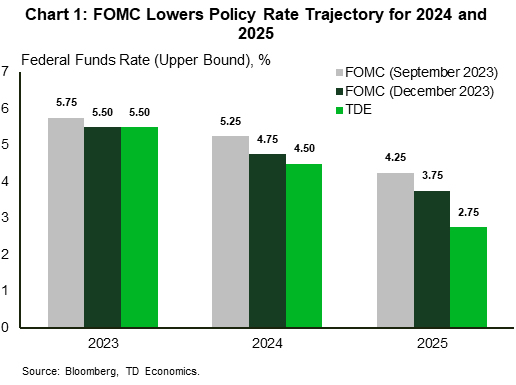

Slightly diverging paths for inflation between the advanced and emerging economies is likely to create dynamics where modest divergences in monetary policy trends will also exist between G10 and EM central banks. We believe policy interest rates in the advanced and developing economies are set to come down over the course of 2024; however, we believe central banks in the advanced economies are on pace to pull forward the timing of pivoting to interest rate cuts, while in the emerging markets, we believe policymakers may opt for a more cautious approach to additional easing or beginning interest rate cuts. As far as the outlook for G10 central banks, the “higher for longer” stance that many institutions adopted in 2023 is becoming less of a priority (Figure 5). For the Federal Reserve, our base case remains for an initial 25 bps rate cut to be delivered in June 2024. Risks around that outlook are now tilted toward earlier rather than later, especially after the FOMC added more cuts into its December “dot plot” and Fed Chair Powell took a slightly more dovish stance in his recent communications to financial markets. In our view, a Fed rate cut could be delivered as early as May, particularly if U.S. inflation trends continue to behave. The tightness of the U.S. labor market and still-strong consumer spending make our base case still June for the start of the Fed’s easing cycle, but should employment and spending trends soften, these dynamics would offer an additional argument in favor of earlier easing.

We also believe a case is being made where European Central Bank (ECB) policymakers can deliver earlier rate cuts. As we highlighted earlier, we believe the Eurozone economy is already in recession and sentiment surveys remain downbeat. From an economic health perspective, ECB easing should probably be pulled forward. In addition, Eurozone inflation has come down markedly in recent months, also creating circumstances for earlier ECB easing. ECB President Lagarde acknowledged these developments at the December monetary policy announcement, as the central bank lowered both its economic growth and CPI inflation forecasts. For the time being, the ECB continues to push back against the idea of early rate cuts; however, if the recent weak trends in economic growth and inflation continue, we believe the ECB’s resistance to monetary easing will eventually wane. As a result, we now forecast an initial ECB Deposit Rate cut sooner than previously anticipated and expect a 25 bps Deposit rate cut to 3.75% at the April 2024 meeting. Also in Europe, we forecast an initial rate cut from the Swiss National Bank in June. But given recent subdued growth and inflation trends, SNB policymakers may also be among the central banks that pulls forward the timing of rate cuts. While we do not expect the timing of easing to shift forward, we do, however, believe the Bank of Canada (BoC) may be the earliest rate-cutter in the G10. Canada’s economy contracted during the third quarter, and higher interest rates are translating into a rising interest burden for Canadian households, suggesting activity will remain weak. At the same time, Bank of Canada has made more progress than most central banks in bringing inflation closer to target. As a result, we remain comfortable with our view for an initial 25 bps rate cut, to 4.75%, in April 2024. More generally, we also see a steady series of BoC rate reductions that will lower the central bank’s policy rate by a cumulative 225 bps to 2.75% by mid-2025.

To be fair, the conversation for G10 central banks is not entirely centered around earlier monetary easing. Bank of England (BoE) policymakers, for example, continue to push back against premature rate cuts. Despite a favorable October inflation read, core CPI inflation remains above target and wage growth remains elevated. Given U.K. economic fundamentals that suggest stubborn inflation pressures could persist, we believe our previous call for an initial rate cut in May 2024 could be too soon. While the exact timing of initial BoE easing will depend on how activity and inflation data evolve, in our base case we have pushed back our forecast for the first Bank of England rate cut to the August 2024 meeting. That said, as inflation slows through late 2024 and into 2025, we see an extended period of monetary easing and expect 225 bps of BoE rate cuts, taking the Bank Rate to a low of 3.00% by mid-2025. Sticking with the outlier theme, but working against the theme of policy rate cuts in 2024, is the Bank of Japan (BoJ). In fact, of the G10 and major emerging market central banks, the Bank of Japan in the only institution where a rate hike is a strong possibility at some point in 2024. BoJ Governor Ueda spurred speculation of normalizing monetary policy (i.e., raising interest rates out of negative territory) when he said his role as head of the central bank would become more challenging in the new year. Subsequent commentary from BoJ officials have suggested, however, that there is not enough evidence of strong wage growth to support sustainable inflation in Japan just yet. As a result, our base case scenario for the Bank of Japan is still for policymakers to raise the policy rate 10 bps to 0.00% at the April 2024 announcement. In addition to coming out of negative policy rates, we also believe the BoJ will end its Yield Curve Control policy in April and let Japanese Government Bond yields float more freely and be market determined.

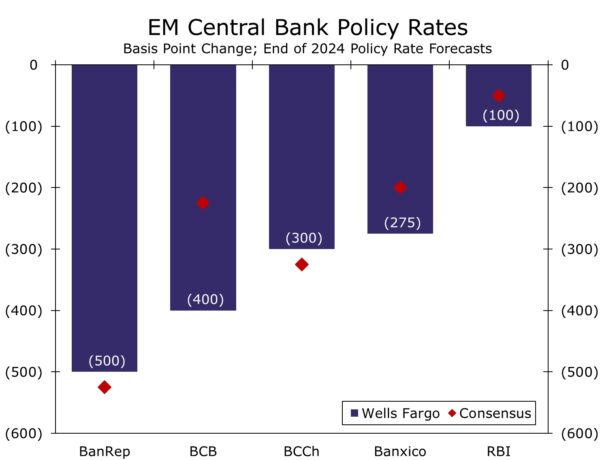

A rapid decline of inflation in 2023 meant that emerging market central banks, including most in Latin America and Eastern Europe, were the first to begin lowering benchmark interest rates. Central banks in Brazil, Chile and Peru have been easing monetary policy for most of 2023, while institutions such as the Hungarian National Bank and National Bank of Poland have been lowering policy interest rates as well. In addition, the stop-start nature of China’s economy prompted sporadic easing from the People’s Bank of China during 2023. While we expect most developing economy central banks to continue, or start, easing in 2024 (Figure 6), less-than-ideal inflation trends could mean policymakers adopt a version or variation of “higher for longer” when considering the paths ahead for monetary policy. These forms could mean slowing the pace of rate cuts, keeping the pace of cuts steady, or delaying the initiation of an easing cycle. The Chilean Central Bank (BCCh) fits this mold quite well. Chilean policymakers began their easing cycle with an aggressive 100 bps rate cut in July 2023, before downshifting to a 75 bps cut in September and a 50 bps cut in October. Given a more gradual slowing of inflation in recent months and Chilean peso instability, we expect the Chilean central bank to stick with a cautious approach to rate cuts. In December and January, we expect Chile’s central bank to continue with 50 bps rate cut increments, and starting in April 2024, to downshift even further to 25 bps rate cuts. High inflation is also underpinning our call for delayed monetary easing in Colombia. We expect the central bank to remain on hold this year and for Colombia’s policy rate to end 2023 at 13.25%. Rate cuts are likely to begin in Q1-2024, with Colombia’s central bank potentially picking rate up the pace of rate cuts later in the year as the Fed begins easing. We also pushed back the start of Mexico’s easing cycle to March 2024 as policymakers continue to exhibit caution in the face of uncertainty around the local inflation outlook. Finally, we have also pushed back our forecast timeframe for monetary easing from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). RBI policymakers delivered a “hawkish hold” at its last meeting of the year, keeping its Repo Rate at 6.50% and saying its focus would remain on the withdrawal of policy accommodation. Against this backdrop, we now see the RBI delivering an initial 25 bps rate cut in Q2-2024 compared to Q1-2024 previously, while for all next year we see a cumulative 100 bps of rate reductions, which would bring the repo rate to 5.50% at the end of 2024.

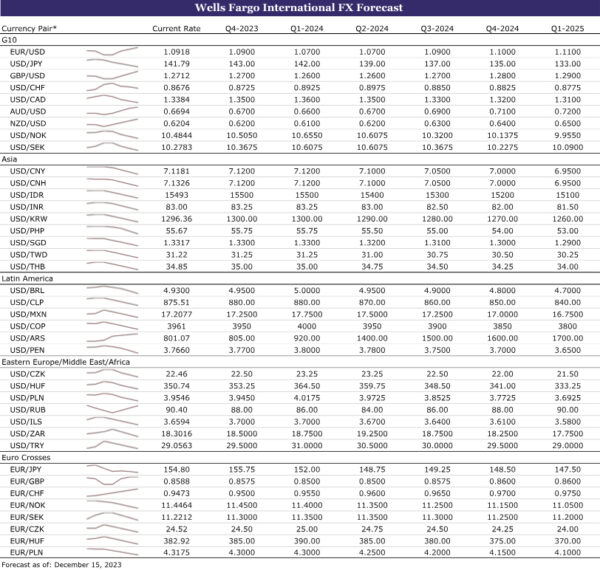

U.S. Dollar Heading for Trend Depreciation in 2024

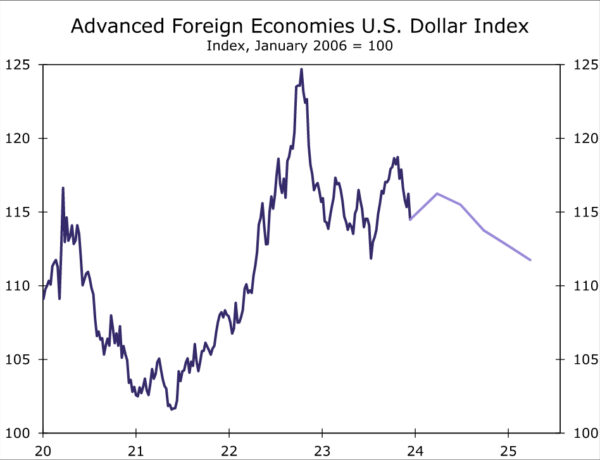

Our outlook for currency markets in 2024 is little changed. While we suspect the U.S. dollar could experience a brief period of strength into early next year, we believe the more significant trend will be one of extended U.S. dollar depreciation through most of 2024 and into the early part of 2025. In terms of the near-term prospects for the U.S. dollar, we believe most G10 central banks will opt to remain on the sidelines in the immediate months ahead, with rate cuts unlikely to be delivered until Q2-2024 or later. Against a backdrop of steady monetary policy, we believe relative growth and economic performance will be the main driver of currency performance in the near term. In our view, the U.S. economy is still outperforming G10 peers and the U.S. resilience story remains intact. The U.S. economy grew 5.2% quarter-over-quarter annualized in Q3-2023, and November nonfarm payrolls rose by 199,000. Despite the jobs number being inflated by the return of striking workers, the U.S. labor market remains in solid shape. U.S. resilience stands in stark contrast to European economies that are either close to or already in recession, as well as a Canadian economy that also contracted in Q3. In that sense, we believe relative economic performance will be supportive of the U.S. dollar through Q1-2024. Further greenback strength is likely to be modest, however. We expect only moderate U.S. dollar gains against G10 currencies and, to a lesser extent, dollar strength against emerging market currencies.

As 2024 progresses, however, we expect growth and monetary policy fundamentals to become less supportive of the U.S. dollar. Our base case remains for a mild U.S. recession during mid-2024, meaning that the U.S. economy would transition into contraction just as regions that are currently struggling—Eurozone, United Kingdom, Canada—are stabilizing (Figure 7). As relative U.S. growth performance against the G10 economies, and indeed, emerging economies diminishes, we expect a turn to U.S. dollar weakness and foreign currency strength. As growth trends in the U.S. soften, we expect the Fed to begin shifting monetary policy in a more accommodative direction. While the Fed is likely to deliver an initial 25 bps rate cut, we expect easing to accelerate to 50 bps rate cut increments at select subsequent meetings. As a result of Fed easing, in conjunction with a U.S. recession, we see increasing reasons for a quicker pace of U.S. dollar weakness as 2024 progresses. In fact, the possibility of earlier or faster Federal Reserve interest rate cuts would have important implications for the U.S. dollar. Directly, they would reduce interest rate support for the greenback, acting as a headwind for U.S. dollar gains in the near term and a tailwind for U.S. dollar declines over the longer term. Indirectly, to the extent that the possibility of earlier or faster easing and lower bond yields in the U.S. supports broader equity and financial market sentiment, “safe-haven” support for the U.S. dollar could diminish. Without safe-haven capital flows, U.S. dollar losses could be magnified. Thus, whether the U.S. economy slips into recession or achieves a soft landing, further inflation progress that leads to lower U.S. yields can contribute to overall U.S. dollar depreciation in 2024 and through the remainder of our forecast horizon (Figure 8).

Within the G10, candidates for currency outperformance include those where growth is expected to remain reasonably steady, or at least avoid economic contraction, and where interest rates are likely to stay relatively high. In addition, currencies that are traditionally risk sensitive can perform well in 2024. Using these criteria for outperformance, we believe the Australian dollar and Norwegian krone can be the notable outperformers in the G10 currency space. To a lesser extent, we also believe the New Zealand dollar can strengthen more than peer G10 currencies. Given our view for the Bank of Japan to embark on policy normalization in early 2024, we also believe the Japanese yen can benefit from an improving interest rate differentials due to a global environment of monetary easing. In terms of G10 currency laggards, weak Eurozone growth and early ECB monetary easing should prevent significant euro appreciation, and we believe the euro will underperform over the course of 2024. Relatively early Bank of Canada rate cuts will also restrain Canadian dollar gains. We view emerging market currencies as particularly well-placed for appreciation during 2024. As we highlighted earlier, we expect policy rates to trend lower; however, nominal and real interest rates are still attractive in the developing world. Carry opportunities should drive capital flows to emerging market currencies, while a cautious approach to rate cuts should maintain a degree of carry appeal for many developing market currencies especially as the Federal Reserve approaches more accommodative monetary policy. Finally, in regard to the rising probability of a U.S. soft landing, to the extent the U.S. avoids recession which in turn supports equity markets, this would also be supportive of risk-sensitive currencies. Emerging market currencies tend to be some of the more sensitive to risk appetite, and should risk sentiment improve in a U.S. soft-landing scenario, currencies in Latin America and EMEA should be able to perform well and outperform relative to the G10 currencies.

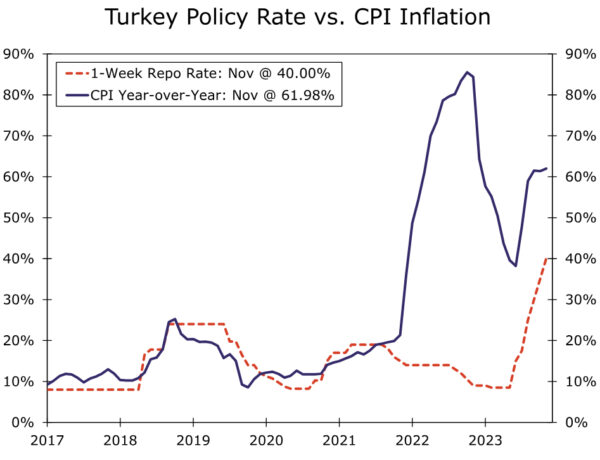

Worth mentioning are a few currencies with interesting idiosyncratic stories that can sway local currency performance regardless of the path of the U.S. dollar and global trends. We opt to highlight two countries where economic and currency trends have seemingly moved in lockstep for years: Turkey and Argentina. In Turkey, President Erdogan has appointed a technocratic team to decide economic and monetary policy. New cabinet members have delivered significant monetary tightening in an effort to contain inflation, a stark shift in monetary policy ideology from what President Erdogan had put in place prior to elections (Figure 9). A more orthodox stance on monetary policy has attracted foreign investors back to Turkish government bonds and has brought Turkish assets back onto investor radars. Up until now, the lira has not recovered as the implementation of technocratic policy needs to build a longer track record of success and “Erdogan risk” hovers over the currency; however, we do believe the lira is on the brink of a rebound in 2024. Turkey will host local elections in March 2024, and while the outcome is not particularly meaningful, President Erdogan’s recent ability to relinquish monetary policy to central bankers will be tested pre- and post-election. In our view, the central bank will now maintain its independence leading into the election and after the election. Interest rates will remain high, inflation will gradually recede, sovereign credit rating upgrades will be delivered and the lira will begin its recovery, although likely along a rocky and non-linear path. In that sense, we now believe the Turkish lira will outright strengthen starting in Q2-2024 and lira strength will continue through early 2025. Conviction in this new lira outlook is not strong, however, and should the policy backdrop change, our view would snapback to forecasting lira depreciation.

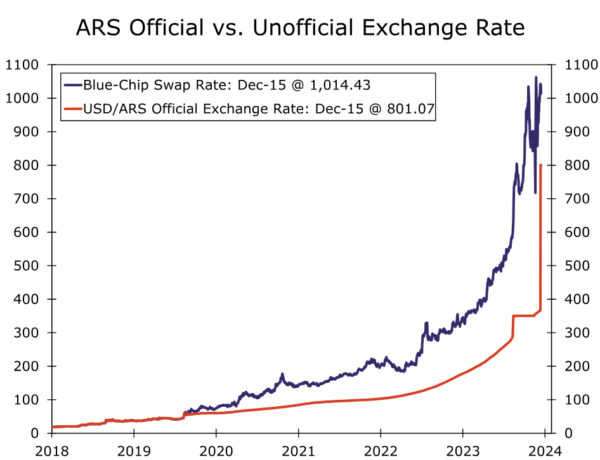

Argentina is also on a tentative path to recovery; however, “tentative recovery” does not translate to an optimistic view on the peso. Now that Milei has secured the presidency, he and his team have delivered a 54% devaluation of the peso and cut fiscal expenditures drastically to correct imbalances. While sovereign credit and local equities have rallied after Milei’s victory, we believe one more peso devaluation of ~25% will be delivered as Milei fully lifts capital controls. We believe this devaluation will occur likely in Q2-2024, and the official USD/ARS exchange rate will weaken sharply. Right now, the unofficial exchange rate in Argentina is hovering around ARS1000, and we expect the official rate to comfortably breach this level by mid-2024 (Figure 10). Following the free float of the peso, the outlook for Argentina’s economy will improve, but the peso is unlikely to materially change course. Currency devaluation will be followed by a sharp rise in inflation, keeping real interest rates in negative territory for an extended period of time. Argentina is likely to receive IMF disbursements, but FX reserves will be limited for the time being and sovereign default risks will remain high. The ability for Milei to deliver on his platform to dramatically alter the policy mix in Argentina and make progress toward economic stability will be key to the longer-term peso outlook. For now, while we believe Milei was the best option to potentially correct Argentina’s economic imbalances, we will need to see a longer-term track record of success and credibility before altering our outlook on the peso. We believe the USD/ARS exchange rate can hit ARS1600 by the end of 2024.

Geopolitical and Political Calendars Are Jam-Packed

Monetary policy and inflation trends have been the main drivers of financial markets for the past two years; however, with active military conflicts in Europe and the Middle East, geopolitics are becoming top of mind for market participants in 2024. Geopolitics has been a constant theme in our publication sets since the Russia-Ukraine conflict started, and our focus on geopolitical developments has intensified as a result of the Israel-Hamas war. But rather than thinking about the short-term direction of each conflict—which we do not have particular visibility into—we have focused on the potential long-term implications of each conflict and worsening global geopolitical relations more broadly. In our view, one of the clearest long-term effects of military confrontation and a deteriorating geopolitical environment will be deglobalization. We argued for most of this year that deglobalization has been occurring for some time; however, the removal of Russia and Russia’s closest allies from the global marketplace will reduce the interconnectedness of the world’s economies and exacerbate deglobalization. We also noted, and continue to believe, the Israel-Hamas war, in combination with the Russia-Ukraine conflict, will force countries around the world to show support for certain sides of confrontations. As countries demonstrate their respective support, geopolitical barriers are likely to be erected and the cross-border flow of goods, services, capital, people, information, etc., is likely to be disrupted and create new deglobalization forces. In our view, 2024 will be a year when these geopolitical fault lines start to become more visible. The deglobalization inertia that has already been in place is likely to gather momentum as neither of the conflicts approaches an end and sentiment around each conflict remains tense. Over the course of 2024, we believe clearer evidence that the integration of the world’s economies is in retreat and recoiling along geopolitical borders will become apparent.

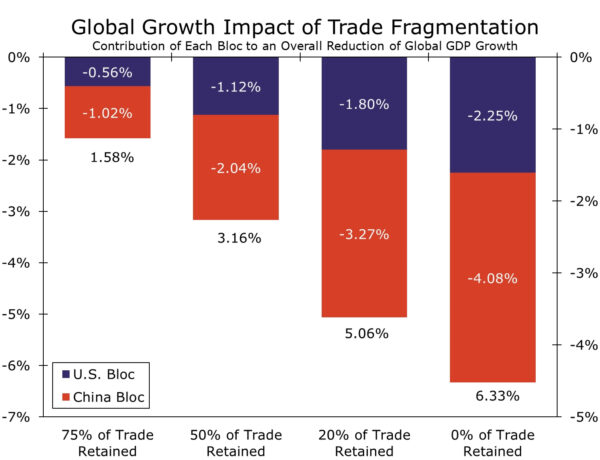

Taking deglobalization a step further, we have also argued that the global economy is at risk of fragmenting due to rising geopolitical hostilities. While the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas conflicts can play a role in fragmentation, a fracturing of the global economy is likely to be a result of geopolitical tensions between the United States and China. While the U.S. and China have not become directly involved in either conflict from a military perspective, both countries have maintained diplomatic engagement in an effort to advance/protect their strategic—and often competing—objectives. The U.S. is providing resources directly to Ukraine and Israel to aid the defense of their respective sovereignties. On the other hand, China has committed to an unwavering friendship with Russia and has used more tactful language to address the Israel-Hamas confrontation. These opposing stances have put a wedge between the U.S. and China on two of the most serious military conflicts in recent history. Tensions between the U.S. and China were already present, and while hostilities between the two nations have escalated irrespective of these conflicts, opposing directions of support does not bode well for any potential improvement in U.S.-China relations in 2024. In fact, when considering the intersection of geopolitics and deglobalization, U.S.-China tensions are arguably at the heart of global economic fragmentation. And with the U.S. and China representing the world’s two largest economies, each country holds a strong gravitational pull for nations around the world to enter their respective orbits. Given the tensions between the U.S. and China, the geopolitical fault lines we expect to form could, over the long term, evolve in a way where countries choose to align themselves with either the U.S. or China. While alignment could take shape in various ways, the most likely form would be two separate blocs of countries: one led by the United States and another by China. We ran a simulation for how fragmentation could occur (i.e., how countries could align themselves) and the global economic impact of fragmentation. In a scenario where the global economy broadly fragments, where trade between the U.S and China blocs are completely severed, the global economy could lose ~6.5% of overall output (Figure 11). We noted earlier how the global economy is already facing growing pains in 2024. While broad fragmentation may not happen in 2024, we do believe the geopolitical landscape is evolving in this direction. Should fissures occur earlier than we expect, or if new military conflicts break out that exacerbate deglobalization, fragmentation could be pulled forward and permanently lower global growth prospects. A fractured economy would also make “weathering the storm” more difficult.

Geopolitical developments have the potential to change economic trends, both short and long term; however, country-level politics can also be influenced by the evolution of geopolitics. Most of our 2024 International Economic Outlook is focused on global growth prospects and monetary policy, but the direction of local politics and the potential influence geopolitical developments can have on elections may arguably be the most fascinating theme of 2024. Next year, many of the world’s largest economies will host general and legislative elections. In fact, countries worth a collective 38% of global nominal GDP—possibly higher due to the lack of precision around the timing of U.K. elections—will host general elections to determine new government leadership (Figure 12). Extrapolating out elections to include congressional and legislative votes, around 55% of the world’s economy will go to the polls in 2024. Elections are spread across the advanced and emerging economies, although the majority of next year’s voting will take place in the developing world. Large emerging economies such as India, Mexico, Russia, Indonesia, Taiwan and South Africa will vote to determine the direction of national policy, and given the current geopolitical landscape, we expect foreign relations and geopolitical alignments to be a point of contention in many of these elections. U.S. elections will be important for the global economy and political backdrop in 2024, and the U.S. election will also be a prime example of where geopolitics is likely to intersect with local politics. Continued U.S. support for Ukraine and Israel has become a source of political fracturing between the left and right, and is potentially causing divisions within the Democratic Party itself.

As of now, US. politicians have not reached a bi-partisan longer-term resolution on additional Ukraine support nor whether to provide further aid to Israel. In our view, federal aid plans could play a role in determining voter intentions during the U.S. election cycle next year, especially as aid fatigue continues to set in. As mentioned, the left side of the political spectrum seems to be most fractured on whether U.S. aid should continue to be deployed to Israel, while cracks may also be forming on Ukraine support. Should contentious sentiment on foreign aid, in particular to Israel, continue to spread across the Democratic Party, the political right could potentially benefit come election time. For now, opinion polls suggest President Biden will meet Donald Trump in November. While we will not offer a view on who will win the election, a second Biden term will likely yield policy continuity, especially in a split congress. In addition to Ukraine and Israel, we would expect a second Biden administration’s foreign policy platform to target China. Applying pressure to China via export restrictions on intellectual property and technology capabilities will likely be a priority. At the same time, a second Trump administration could also make China the centerpiece of its foreign policy strategy. Similar trade restrictions would likely be applied, and existing tariffs are likely to remain in place. Tariff strategy may become a tool employed by a Trump administration again, especially if “Phase I” trade deal targets are not met or perceived as not being reached, or if a “Phase II” trade agreement is not pursued in a timely fashion. Foreign policy toward Taiwan could also be adjusted depending on the outcome of the election. For most of his time in office, President Biden has communicated that the U.S. stance on Taiwan would be to defend the island against any Chinese invasion attempt. This stance would likely continue in a second Biden term; however, a shift back to strategic ambiguity may be pursued in a Trump administration. While the first Trump administration went away from prior U.S. policy and engaged with Taiwan from 2016-2020, a second term could see Taiwan policy shift in a less explicit direction on defense, possibly even using Taiwan’s national defense as leverage and a bargaining tool with China.

U.S.-China-Taiwan relations will also be a focus in the context of Taiwan’s presidential election. On Jan. 13, Taiwan will host elections where the incumbent Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is currently leading in polls. DPP values and ideologies are centered around pushing back on the “One China” notion, and making progress toward Taiwan separating from China and achieving sole sovereignty. However, DPP popularity is being tested and the party’s lead has shrunk over the past few months. Benefiting is Taiwan’s Kuomintang (KMT). KMT core values are for stronger relations with China, improved cross-strait sentiment and a full embrace of the “One China” policy. From China’s perspective, an outcome that inches closer to reunification of the mainland is preferred—meaning KMT is China’s ideal winner—while a result that catapults the Taiwan independence movement forward could result in a further deterioration in cross-strait relations. With DPP still leading, a scenario exists where Chinese aggressions toward Taiwan increase due to a less ideal election outcome. In this scenario, U.S. officials in the Biden administration could reiterate defense support for Taiwan, and U.S.-China relations could suffer. Regardless of the outcome of Taiwan’s election and the China response, we do not believe a China invasion of Taiwan is imminent. We also believe that any Taiwan dollar or Chinese renminbi currency volatility on the back of the election outcome will be short-lived as Chinese military offensive fears recede. In addition, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and Taiwan’s central bank heavily intervene in FX markets to keep their respective currencies stable. Should any volatility ensue after the election, we expect both institutions to act in a manner to achieve stable local currencies, and we are not baking any political risk premium into our Taiwan dollar or Chinese renminbi forecasts in 2024.

Geopolitics could also play a role in Russia’s election; however, President Putin is likely to be in office following Russia’s 2024 election. In our view, Putin maintains a firm grip on the power apparatus in Russia and his time as a politician is not in jeopardy due to the ongoing conflict in Ukraine or at risk from widespread social discontent. While a path to Russia-Ukraine peace is difficult to envision at this time, a second Trump administration could be more willing to negotiate and interact with Russia than a Biden administration. Getting Ukraine to sign on to any peace agreement that shrinks the country’s geographic presence will probably be an impediment to a truce, and with Russia’s economy staving off sustained sanctions-led disruptions, sanctions relief may not be much of an incentive for President Putin to pursue peace. For now, our global economy and FX forecasts as well as our deglobalization and fragmentation views assume the Russia-Ukraine conflict will persist for the foreseeable future. Should a cease-fire, outright peace, or an escalation materialize, our forecasts and select views could change, but as mentioned, we are not currently in a position to forecast or assume a change in the direction of the conflict. As far as the Russian ruble, strict capital controls and Bank of Russia interest rate hikes should prevent the ruble from any outsized depreciations similar to 2022. We assume that over the course of 2024, Russian policymakers ease capital controls and ruble selling becomes more possible. In that sense, we forecast a weaker ruble for most of next year, but tight monetary policy and lifting dollar-buying restrictions should make for a gradual selloff despite our view for broad-based U.S. dollar depreciation.

There are also elections where geopolitics may not loom as large. Elections in India and Indonesia are not likely to have a geopolitical element to them. South Africa’s presidential election is also likely to be influenced more by domestic issues and local economic malaise, while voting intentions in Mexico are also likely to be focused on the direction of domestic policy. As far as elections in India and Indonesia, we expect little political risk to build ahead of each election, and for the rupee and rupiah to experience little, if any, political induced volatility. In India, Narendra Modi is all but certain to win another term as prime minister. Recent state elections yielded a strong performance for Modi’s BJP, and his approval ratings and popularity remain elevated amid an Indian economy that is on solid ground. Legislative elections will be key. A divided congress could limit India’s overall reform agenda and integration into the global economy; however, we believe Modi will secure victory in a relative landslide, despite more aggressive and unified opposition efforts to unseat Modi. Mexico’s election is likely to be a bit more contentious relative to India, and we do factor a mild rise in political risk into our Mexican peso forecast. We believe AMLO’s MORENA Party successor—Claudia Sheinbaum—will win the presidency in June. Sheinbaum is running on an inward-looking, anti-foreign capital platform, which is modestly concerning given Mexico’s need for foreign investment, and given its position to potentially benefit from nearshoring. With that said, the composition of congress will be more important and will determine whether Sheinbaum can implement her policy suite. A congressional majority or supermajority, similar to what AMLO won in 2018, could inject more volatility into the peso. Should we get a sense for broad support for Sheinbaum’s policy platform, we would adjust our peso forecast to reflect more short-term depreciation. For the time being, we forecast peso depreciation to gather momentum in Q1/Q2-2024 as political risk rises ahead of the election. And finally, elections in South Africa are likely to be the most disruptive to local financial markets. Constant power outages and load-shedding at Eskom have reduced potential GDP growth for South Africa’s economy significantly over time. Historically, the African National Congress (ANC) has dominated South Africa’s political structure. But with the economy in distress and prospects rather dim, South Africa could be ripe for political turnover or enhanced fiscal spending as a way to rally support. We expect ANC officials to use fiscal policy as means for electoral support, and given South Africa’s already weak public finance profile, wider deficits and a higher debt burden can weigh on South Africa’s local financial markets. Even though we believe the rand can strengthen in 2024, elevated political risk and the rising likelihood of ANC officials implementing populist policies should lead to rand underperformance relative to peer emerging market currencies.

High Conviction Views

Global growth to soften further next year. Growth in global economic activity has peaked, and we remain convinced GDP growth will slow further next year. G20 GDP growth decelerated to 2.9% year-over-year in the third quarter, and sentiment surveys point to a further slowing in the pace expansion moving forward. That outlook is also supported by the impact of higher interest rates that are increasingly being transmitted across the global economy, as well as a gradual slowing in employment growth. Activity is already stalling or contracting in several economies, including the Eurozone, Japan, United Kingdom and Canada, while we also expect growth to slow in the United States and China in 2024. Against this backdrop, we see global GDP growth slowing from 2.9% in 2023 to 2.4% in 2024, before a moderate rebound in the pace of expansion in 2025.

We expect broad U.S. dollar depreciation to gather pace in 2024. While the U.S. economy’s relative resilience could support the greenback into early next year, we expect broad U.S. dollar depreciation as 2024 progresses. Progress on the inflation front means Fed rate cut risks are tilted toward sooner rather than later, which should limit any greenback gains. A hard landing or U.S. recession next year would see interest rate and growth trends swing against the U.S. currency. A soft U.S. landing, combined with inflation progress and lower U.S. yields, could support broader financial market sentiment, which would also weigh on the “safe-haven” support for the U.S. dollar. As the global monetary policy cycle turns to easing, broad U.S. dollar depreciation is looking increasing likely across a wide range of scenarios.

We expect the Australian dollar to outperform next year. We expect solid gains from the Australian dollar as 2024 progresses. While Australia’s economic growth should slow next year amid an uncertain Chinese outlook, we do not expect an outright decline in activity. That is in contrast to the mild recession we forecast for the U.S., a relative growth performance that should support the Australian currency. Moreover, with Australian inflation elevated and receding only gradually, further Reserve Bank of Australia monetary tightening cannot be ruled out, while rate cuts are unlikely until late next year. Australian monetary easing should lag that of the Fed and, together, relative growth and monetary policy trends should be supportive of the Australian dollar in 2024.

One last Argentine peso devaluation. President Milei delivered the first peso devaluation of his administration, and in our view, will deliver one final sharp depreciation as capital controls are fully lifted. We believe this peso devaluation will occur in Q2-2024, after a quarter of crawling depreciation that will eventually prove untenable due to insufficient FX reserves. We expect the peso to be devalued around 25% and for the currency to approach ARS1400 against the U.S. dollar by mid-2024.