Live Comments

US initial jobless claims fall to 227k, above exp 222k

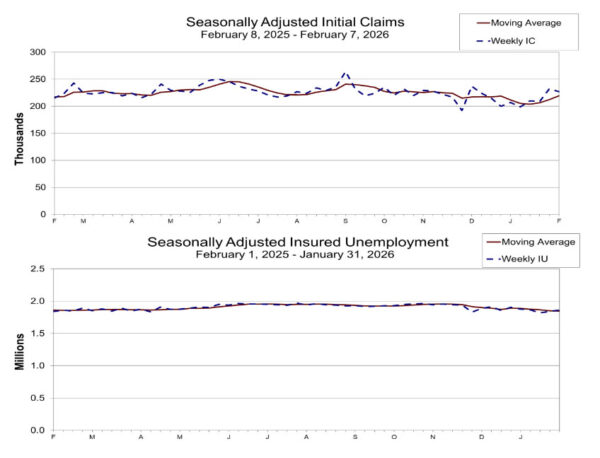

US initial jobless claims fell -5k to 227k in the week ending February 7, above expectation of 222k. Four-week moving average of initial claims rose 7k to 219.5k.

Continuing claims rose 21k to 1,862, in the week ending January 31. Four-week moving average of continuing claims fell -3k to 1,847k, lowest since October 5, 2024.

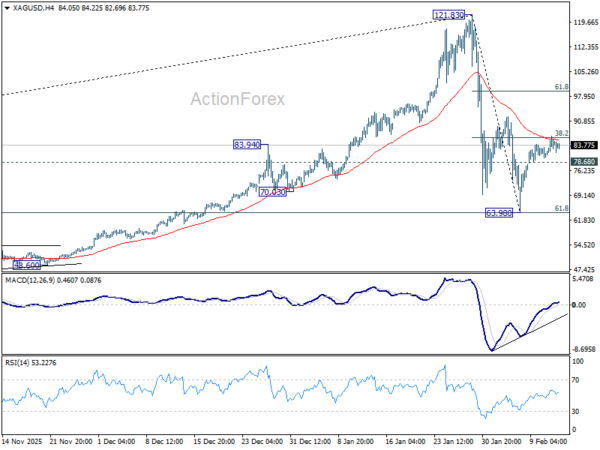

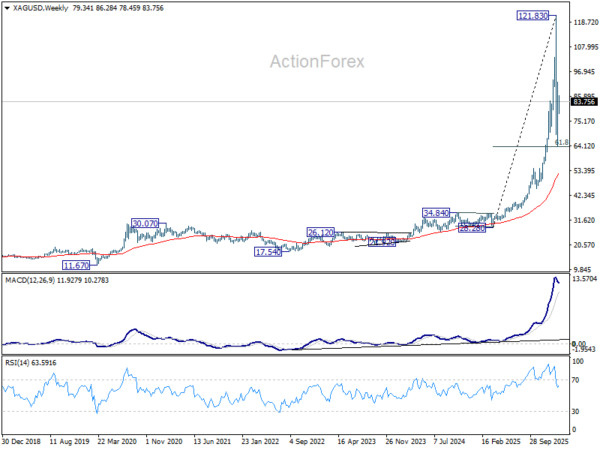

Silver push toward 100 hinges on 85/86 key barrier break

Silver is now pressing into a critical near-term resistance cluster around 85–86, a zone that could determine whether the sharp selloff from 121.82 has already bottomed at 63.98 or whether another leg lower is still ahead. The area combines 55 4H EMA (now at 85.27) and 38.2% retracement of 121.83 to 63.98 at 86.07, creating a technically dense barrier. Price reaction here is likely to set the tone for the next multi-week move.

Stepping back briefly, strong support emerged at 63.98, around 61.8% retracement of 28.28 to 121.83 at 64.04. That the decline from 121.82 is a correction to the up trend from 28.28 only. While the larger picture still points to prolonged medium-term consolidation, the immediate question is whether the next short-term upswing is about to unfold.

If Silver can sustain trading above the 85/86 zone, it would solidify the case that the first corrective leg completed at 63.98 and that a second leg higher is underway. In that scenario, further rise should be seen to 61.8% retracement of 121.83 to 63.98 at 99.73. However, the psychological 100 level sits just above that target and is likely to cap upside.

Conversely, rejection at 85/86 followed by a break below 78.68 support would shift the bias back to the downside. That would put 63.98 back in view and raise the probability that the correction is deeper than initially thought. In that case, the pullback could extend into a broader correction of the uptrend from 17.54 (2022 low), or even the larger advance from 11.69 (2020 low), before a durable base forms.

For now, the technical picture argues for patience rather than conviction. Silver is sitting at a clear decision point, and clarity should emerge within days. A confirmed break above 86 would favor positioning for a push toward 100, while failure at resistance would suggest waiting for another dip before considering fresh long positions.

RBA’s Hunter: Job market tightness consistent with inflation pressure

RBA Assistant Governor Sarah Hunter signalled that Australia’s labour market remains tight despite signs of moderation elsewhere in the economy. In a speech today, she said the RBA’s full employment and NAIRU frameworks indicate that conditions have stabilized and remain “a bit tight,” consistent with "some inflationary pressure in the economy."

She described the relationship between labour tightness and inflation as “like the entwined double helix,” arguing that persistent capacity constraints continue to underpin price pressures. Recent data support that view, with unemployment unexpectedly falling to a seven-month low of 4.1% in December, raising the possibility that the labor market may be tightening again.

Hunter noted that the slowdown over the past few years has occurred primarily through fewer vacancies, reduced job switching, and slower hiring rather than a material rise in unemployment.